One of the industries that will be most keyed in on what the Fed does with interest rates is the automobile sector, which has used seven years of cheap rates to rebound after nearly capsizing during the financial crisis.

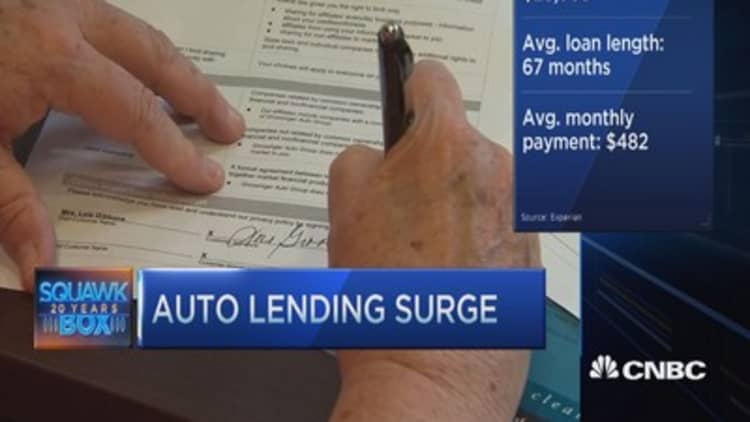

Outside of banks, autos are arguably the most rate-dependent business. Light vehicle sales have about doubled since the crisis lows, from just more than 9 million in February 2009 to just more than 18 million in November 2015. That's still well below the 21.7 million peak in October 2001, but still a strong rebound.

Read MoreIn the season of luxury autos, numbers don't lie

The industry has the Fed to thank for that.

In addition to the $80 billion government bailout for car companies, the U.S. central bank lowered its target funds rate to near zero in late 2008, resulting in bargain-basement lending rates that helped sales surge.

Though on a slightly upward trajectory, a five-year used car loan can still be had for a national average of 2.81 percent, while new-car financing comes with a 3.32 percent rate, according to Bankrate.com. Before the crisis, the same loans were going in the 8 percent range.

It's little wonder, then, that the Fed itself is expecting the auto industry to feel some reverberations once the rate-hiking cycle begins in earnest.

In a white paper examining the impact, the New York Fed concludes that the longer-term effects will be felt in auto sales and manufacturing.

"Overall, we find evidence that interest rate changes have marked effects on sales and production in the automobile market, through both the household expenditure and firm inventory channels," the paper, released Nov. 23. stated.

In all, a 100 basis point, or 1 percentage point, hike in the funds rate would translate to a 12 percent annualized hit to production and a 3.25 percent dent in sales, according to the Fed's models.

Read More

The salient point in the equation is how long it takes the Fed to get to 1 percent.

The current rate is targeted at zero to 0.25 percent and actually sits at 0.14 percent. At its two-day meeting next week, the Federal Open Market Committee is expected to hike the rate a quarter point, to an upper limit of 0.5 percent. Traders currently are pricing in an 85 percent chance of a hike, according to futures data from the CME.

From that point, traders believe there is a slightly better than even chance that the funds rate could be above 1 percent by the November FOMC meeting.

From a consumer standpoint, that is unlikely to mean a lot in terms of costs to an auto loan — about $12 a month for the average loan, according to Greg McBride, chief financial analyst at Bankrate.com.

What concerns McBride — and the Fed researchers — more is the impact on the broader economy.

"The bigger risk is if a succession of rate hikes dents the economy, because if people are concerned about a job loss or making less money, etc. that certainly will hurt car sales," McBride said in a statement to CNBC.com.

The Fed believes there are channels through which a rate increase works, and that is particularly pronounced when it comes to long-lasting, or "durable," goods like autos.

"Economic theory predicts that the durable goods market is a key channel through which monetary policy affects the real economy," the paper said.

Read More Why I'm worried about a recession: Citi strategist

"Higher interest rates raise the cost of borrowing for households, inducing a decline in demand for automobiles," the Fed researchers added. "Hence, sales and real prices should fall. Automakers will react to the decline in demand by curtailing production and their inventories may rise or fall, depending on the size of the sales decline relative to the decline in production."

McBride, though, said he expects the impact to be low with Fed officials pledging that rates will not raise quickly.

"Banks and credit unions alike continue to offer some of the lowest auto loan rates we've ever seen, with sub 3 percent — and in some cases sub 2 percent — rates available on both new and used car loans," he said. "A gradual change in interest rates is not going to change this landscape dramatically."

"The Federal Reserve raising interest rates won't put the kibosh on car sales, however if the economy were to weaken because of the Fed's actions, that would certainly slow car sales."