Researchers in the U.K. have found that blocking a receptor in the brain that regulates immune cells could "protect against the memory and behavior changes seen in the progression of Alzheimer's disease."

According to a news release from the University of Southampton, the research by scientists looking into how Alzheimer's progresses in the human brain has added to evidence that "inflammation in the brain can in fact drive the development of the disease."

The study's findings, published on Friday in the journal Brain, point to the disease potentially being halted if inflammation in the brain is reduced, with hopes of an effective new treatment being developed as a result.

According to the Alzheimer's Association 5.3 million Americans were estimated to have the disease – which has no cure – in 2015. The cost of Alzheimer's to the U.S. is $226 billion, with that figure potentially increasing to $1.1 trillion by 2050.

In the University study, tissue samples from people with healthy brains and those with Alzheimer's – both of the same age – were analyzed by researchers.

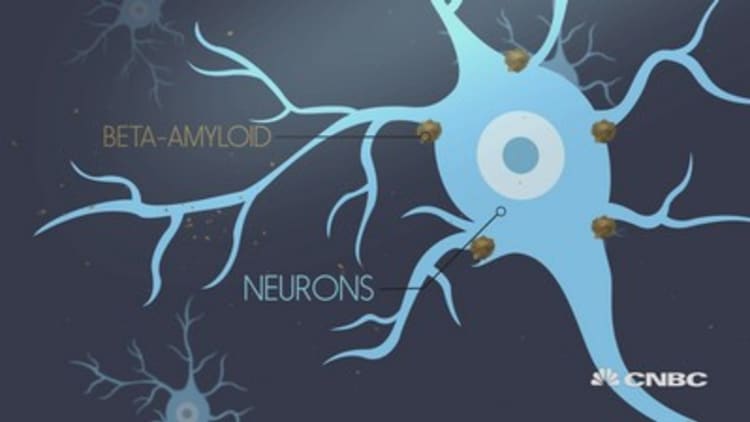

The numbers of a specific type of immune cell – microglia – were counted. The brains with Alzheimer's were found to contain more of these immune cells than healthy ones.

The production of microglia in mice bred to develop the characteristics of Alzheimer's was blocked by researchers. Mice were given a drug which blocks CSF1R, a receptor that regulates microglia.

Compared to mice left untreated, those that had been treated were able to demonstrate "fewer memory and behavioral problems."

"These findings are as close to evidence as we can get to show that this particular pathway is active in the development of Alzheimer's disease," Diego Gomez-Nicola, lead author of the study, said in a release.

"The next step is to work closely with our partners in industry to find a safe and suitable drug that can be tested to see if it works in humans," Gomez-Nicola added.

Doug Brown, director of research at the U.K.'s Alzheimer's Society, was encouraged by the findings.

"With an ageing population and no new dementia drugs in over a decade, the need to find treatments that can slow or stop disease progression is greater than ever," he said.

"Although dementia research is still desperately underfunded, increased commitments from government and charities are boosting UK research efforts and contributing to faster global progress towards a much needed cure."