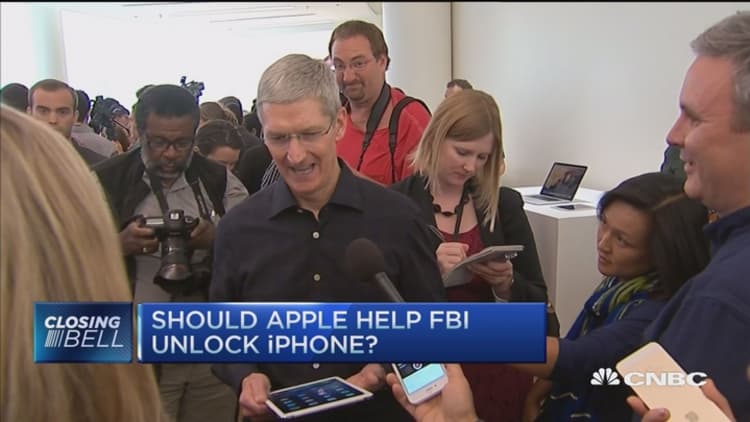

In a statement to customers on Tuesday, Apple's chief executive, Tim Cook, vehemently opposed the FBI's efforts to unlock the iPhone 5C belonging to San Bernardino, California, shooter, Syed Rizwan Farook.

Calling the move "chilling," Cook explained why he believes the All Writs Act of 1789 — the statute the Department of Justice is citing to obtain information in this case — sets a "dangerous precedent."

"If the government can use the All Writs Act to make it easier to unlock your iPhone, it would have the power to reach into anyone's device to capture their data," Cook said in a statement. "The government could extend this breach of privacy and demand that Apple build surveillance software to intercept your messages, access your health records or financial data, track your location, or even access your phone's microphone or camera without your knowledge."

Cook outlined his reasoning for challenging the FBI's demands, but the government's methodology for invoking the All Writs Act is not as clear cut, especially since the statute is considered by some to be relatively obscure.

Drawing its roots from the Judiciary Act of 1789, but updated in the 1900s, the All Writs Act grants federal courts the authority to issue the writs (court orders) that are "necessary or appropriate in aid of their respective jurisdictions and agreeable to the usages and principles of law."

Essentially, the catchall statute allows courts to require third parties' assistance to execute a prior order of the court, according the Electronic Frontier Foundation, a nonprofit specializing in defending civil liberties in the digital world.

Though Cook may have called the use of the act "unprecedented," this is not the first time the government has tried to employ the statute to compel Apple to unlock a seized mobile device.

In October 2015, Magistrate Judge James Orenstein of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, expressed strong doubts that he had legal authority to order Apple to unlock an iPhone in government possession.

"[Apple] is a private-sector company that is free to choose to promote its customers' interests in privacy over the competing interest of law enforcement," wrote Orenstein in his memorandum and court order.

Anthony Sabino, an attorney and law professor at St. John's University, said he agrees with Orenstein's assessment.

"The law is somewhat esoteric. It is just not something that comes into play a lot. It is usually used in situations where there is some sort of conflict between the federal court authority and the state court authority," said Sabino. "As far as characterizing the All Writs Law, it is much more of a jurisdictional statute as opposed to one that truly touches on search and seizure."

The main problem with using the All Writs Act against Apple, Sabino said, is the issue of the government wanting the tech giant to create a master key to access the data from one of the San Bernardino perpetrators' phones. Once the FBI has this key, there is concern that it can access anyone's smartphone, he added.

"I trust the FBI, and I believe in the FBI, but I don't know if I want a government agency to search anyone's information without a search warrant," said Sabino. "That's a tremendous amount of power to hand over. Once you let the genie out of the bottle, you can't get him back in."

It's unclear why the FBI would use the All Writs Act to bypass the Fourth Amendment to obtain iPhone data, Sabino said. This strategy may, however, have to do with the surveillance revelations from Edward Snowden.

"Companies do not want to be seen as facilitating investigations since it is not good PR for them," said Darren Hayes, assistant professor and cybersecurity director at Pace University's Seidenberg School of Computer Science and Information Systems. "There has been a tremendous shift away from support for law enforcement of these companies."

Hayes speculated that since companies like Google and Apple have not recently been particularly helpful to law enforcement, the government decided to take a different route to obtain the information it wants.

"The tide of public opinion may be with the companies now, but unfortunately, if we start to see more ISIS terrorist attacks where iPhone evidence is really critical, people may be more in favor of investigations and possibly see that the government has a point."