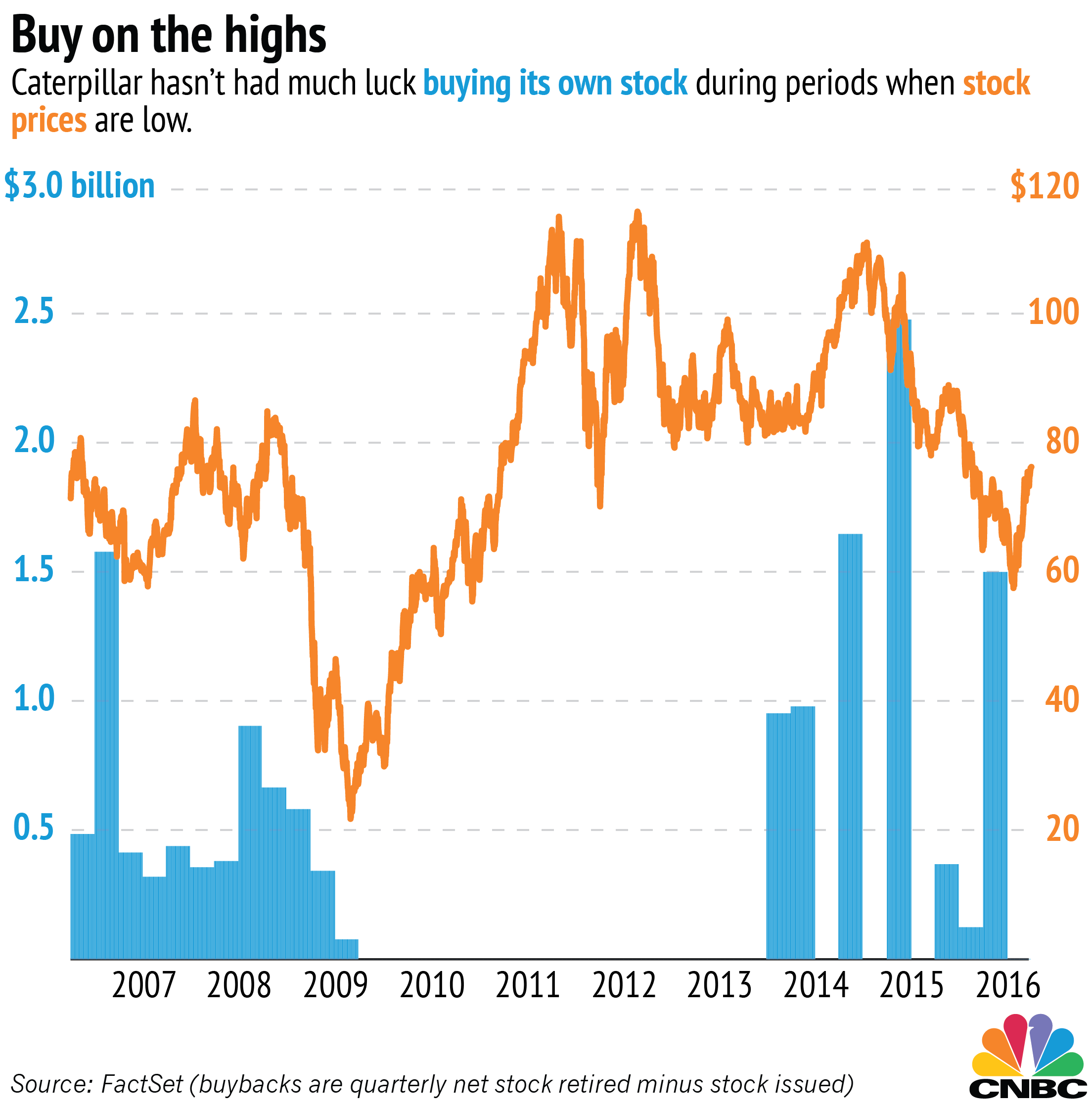

Some companies can't seem to get enough of themselves, buying up their own stock even when it isn't a great deal.

Although one of the main justifications for stock repurchase programs is that management thinks its own stock is undervalued, some companies have tended to buy at all the wrong times. Buybacks are a popular method to return excess cash to shareholders because the moves are considered less permanent than dividends and often inflate stock prices and earnings per share by removing shares from circulation.

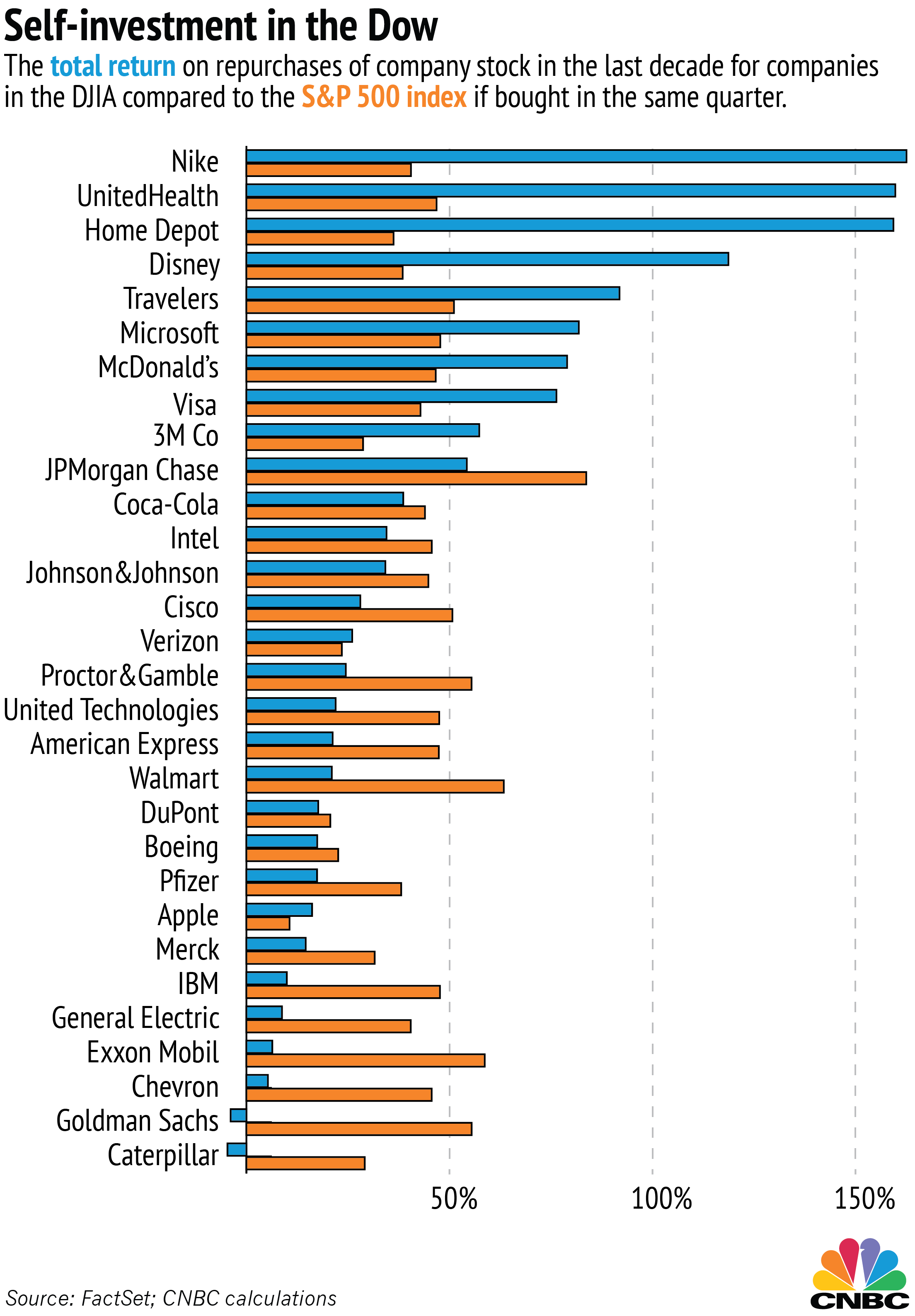

But about two-thirds of the companies in the Dow Jones industrial average would have been better off simply investing their extra cash in an S&P 500 index fund, which would have grown more than their own stock did in the quarters after they bought and retired shares.