It's called the law of supply and demand.

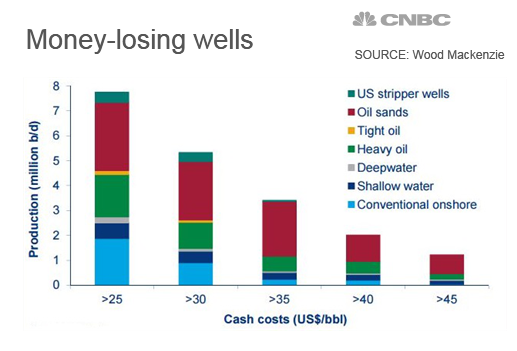

When a commodity costs more to produce than the current market price, producers usually stop producing it. But when it comes to U.S. crude, a global crash in prices hasn't been matched by deep cuts in production.

The biggest impact so far has been felt on investment in new wells, as U.S. producers big and small have slashed capital spending and sidelined drilling rigs. As of this month, about 350 rigs were drilling for oil in the U.S. — about a quarter of the peak in October 2014.