At the crux of the St. Louis Fed announcement Friday that it is changing its method of forecasting was a dismal acknowledgement — the economy essentially has come as far as it's going to go for the next several years.

The conclusion comes via a wonky slog through issues and terminology ("regime change" anyone?) that only an avid Fed follower could love. But a paper released by James Bullard, who runs the St. Louis Fed, was clear in asserting that present conditions are likely to persist for at least the next 2 ½ years, presenting little need for the central bank to raise rates more than a quarter point.

That means economic growth around 2 percent — though without a recession — limited productivity gains and the associated wage hikes, and muted inflation. On its own, that forecast wouldn't be terribly shocking, if it hadn't come from a leading member of a central bank that only a few weeks ago had been talking up rate hikes and economic growth with a strong sense of certainty.

"They've put themselves in an awkward position," said Joseph LaVorgna, chief U.S. economist at Deutsche Bank. "It's been a very weak economy, and interest rates are already extraordinarily low. ... This is as good as it's going to get."

There are multiple caveats to attach to Bullard's report, the most important being that he was speaking only for the St. Louis Fed and not the broader central bank and its Federal Open Market Committee, which sets monetary policy. But with Wednesday's FOMC decision not only not to raise rates in June but also to scale back its economic projections and the path of rates ahead, the timing is at least important.

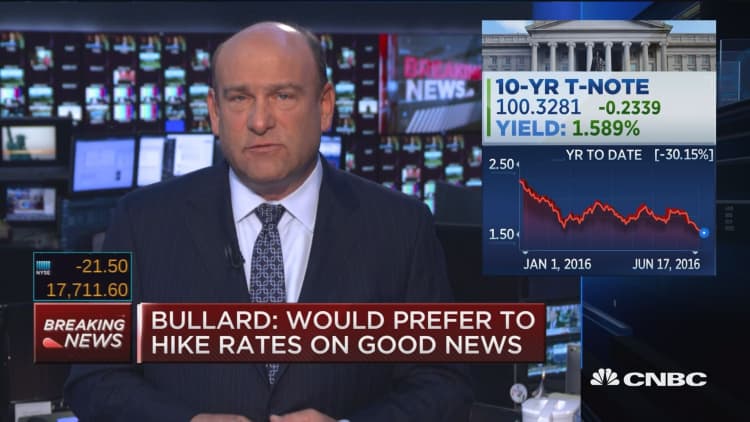

In a nutshell, Bullard's paper said the St. Louis Fed no longer would provide economic forecasts for the medium and long term based on expected fluctuations in data, but rather would use a "regime" base for the near-term conditions that would prevail. Using what he believes is the likely path, Bullard said a Fed rate target of 0.63 percent will be appropriate, meaning the central bank should enact only a single quarter-point hike during the period, with the current funds rate at 0.37 percent.

It was a stunning turn considering the hawkish talk coming out of the Fed before this week's meeting, and, perhaps, a capitulation to the bond and futures markets that had long doubted the central bank would meet its own hiking expectations. As recently as December, Fed officials indicated that four rate hikes in 2016 alone would be appropriate, a notion the futures market rejected. Now, the market believes there won't be any — there's just a 24.9 percent chance of a hike — and Bullard likely just reinforced that.

Wall Street has recoiled at this week's Fed gyrations, with major averages on Friday set to close the week on a down note.

"The market is on its own now. It will make its own assessments, as it has been doing," said Quincy Krosby, market strategist at Prudential Financial. "The market will do its job, whether or not the Fed does its. Invariably, that's how it works."

Bullard's report cites some of the Fed's forecasting errors, of which there have been many over the years, and he says changes to another "regime" different than the current set of conditions is "not forecastable." In his words:

By doing this, we are backing off the idea that we have dogmatic certainty about where the U.S. economy is headed in the medium and longer run. We are trying to replace that certainty with a manageable expression of the uncertainty surrounding medium- and longer-run outcomes.

By doing so, we hope to provide a better description of the nature of the data dependence of monetary policy going forward.

Another factor that made the switch in method even more glaring was how quickly it came, and how it seems to have been precipitated by one data point in particular: The meager 38,000 gain in May payrolls. While Fed officials profess that they don't make judgments based on single reports, this one seemed to shape a belief that the economy was not merely in a cyclical slowdown but rather is experiencing something more along the lines of what economist Larry Summers has called "secular stagnation."

"It reinforced a notion that they're not more prescient than the average person looking at the economy, looking at jobs, and although they may use more erudite language than the rest of us, at the end of the day they still have to see what the data releases tell us," Krosby added.

Investors long have accepted with a wink and a nudge pronouncements from Fed Chair Janet Yellen and her colleagues that the central bank is "data dependent," understanding that the strongest driver of monetary policy has been the financial marketplace.

However, the Fed is now reaching what some term a credibility crisis for not following through on its multiple vows to normalize rate policy since the extreme accommodation precipitated by the financial crisis. The central bank raised rates a quarter point in December, its first hike in more than nine years, a move that was followed by substantial market turmoil.

"When the markets are really robust, the Fed will get more hawkish. When the markets tighten and there's concern about growth, the Fed goes dovish," Deutsche Bank's LaVorgna said. "It's not dissimilar from the market buying the highs and selling the lows. ... The Fed's become too fixated on the markets, but I don't know how at this point they can get away from it."