In 2005, as he was making a transition from developing real estate to capitalizing on his fame through ventures like a reality show and product-licensing deals, Donald J. Trump hit upon a two-pronged strategy for entering the field of for-profit education.

He poured his own money into Trump University, which began as a distance-learning business advising customers on how to make money in real estate, but left a long trail of customers alleging they were defrauded. Their over Mr. Trump's presidential campaign.

But Mr. Trump also lent his name, and his credibility, to a seminar business he did not own, which was branded the Trump Institute. Its operators rented out hotel ballrooms across the country and invited people to pay up to $2,000 to come hear Mr. Trump's "wealth-creating secrets and strategies."

And its customers had ample reason to ask whether they, too, had been deceived.

As with Trump University, the Trump Institute promised falsely that its teachers would be handpicked by Mr. Trump. Mr. Trump did little, interviews show, besides appear in an infomercial — one that promised customers access to his vast accumulated knowledge. "I put all of my concepts that have worked so well for me, new and old, into our seminar," he said in the 2005 video, adding, "I'm teaching what I've learned."

Reality fell far short. In fact, the institute was run by a couple who had run afoul of regulators in dozens of states and had been dogged by accusations of deceptive business practices and fraud for decades. Similar complaints soon emerged about the Trump Institute.

Yet there was an even more fundamental deceit to the business, unreported until now: Extensive portions of the materials that students received after paying their seminar fees, supposedly containing Mr. Trump's special wisdom, had been plagiarized from an obscure real estate manual published a decade earlier.

Together, the exaggerated claims about his own role, the checkered pasts of the people with whom he went into business and the theft of intellectual property at the venture's heart all illustrate the fiction underpinning so many of Mr. Trump's licensing businesses: Putting his name on products and services — and collecting fees — was often where his actual involvement began and ended.

"That Trump Institute, what criminals they are," said Carol Minto of West Haven, Conn., a retired court reporter who attended one seminar in 2009 and agreed to spend $1,997.94 to attend another before having second thoughts. She wound up requiring the help of two states' attorneys general in getting a refund. "They wanted to steal my money," she said.

The institute was another example of the Trump brand's being accused of luring vulnerable customers with false promises of profit and success. Others, besides Trump University, include multilevel marketing ventures that sold vitamins and telecommunications services, and a vanity publisher that faced hundreds of consumer complaints.

More from the New York Times:

'We're an Easy Target': Taken In by the Trump Brand

Former Trump University Workers Call the School a 'Lie' and a 'Scheme' in Testimony

At Trump University, Students Recall Pressure to Give Positive Reviews

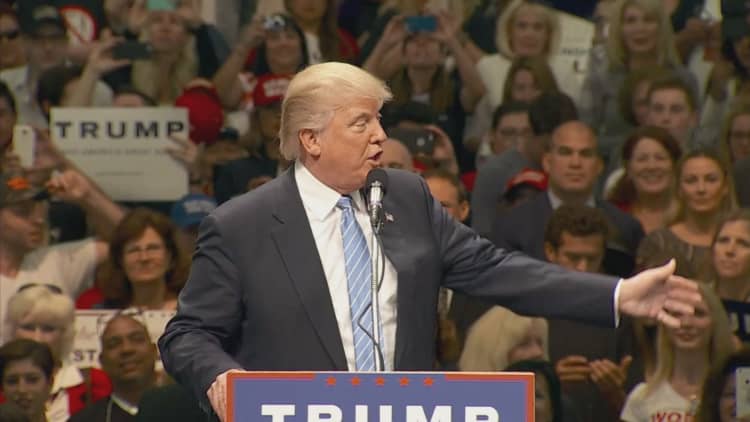

Mr. Trump's infomercial performance suggested he was closely overseeing the Trump Institute. "People are loving it," he said in the program, titled "The Donald Trump Way to Wealth" and staged like a talk show in front of a wildly enthusiastic audience. "People are really doing well with it, and they're loving it." His name, picture and aphorisms like "I am the American Dream, supersized version" were all over the course materials.

Yet while he owned 93 percent of Trump University, the Trump Institute was owned and operated by Irene and Mike Milin, a couple who had been marketing get-rich-quick courses since the 1980s.

A Trump executive, Michael Sexton, told The Sacramento Bee in 2006 that there was a simple reason for going into business with the Milins: Their company was "the best in the business."

Yet the Milins' reputation was actually pockmarked with lawsuits and regulatory actions — a dismal track record that Mr. Trump and his aides could have unearthed with a modicum of due diligence.

The Milins were known for running full-page ads that screamed "FREE MONEY!" and offered tutorials on how to obtain government grants and loans. They were also notorious for being frequent targets of state regulators.

In 1993, the Texas attorney general accused their company, then called Information Seminars International, of taking customers' money and running. People who bought a $499 "Milin Method" package were promised financing to resell real estate purchased at government auctions, officials said, but when customers sought to follow up with the company, the Milins had vanished.

In 2001, operating as National Grants Conference, the Milins settled with Florida authorities after being accused of violating the state's Deceptive and Unfair Trade Practices Act. And in 2006, the Vermont attorney general sued the Milins for consumer fraud, ultimately fining them $65,000 and allowing customers to seek more than $325,000 in refunds.

The regulatory woes continued after the Milins rebranded their seminar business with the name of the country's best-known real estate developer: In 2007, 33 state attorneys general signed a letter to the Federal Trade Commission accusing the Milins of deceptive trade practices. A year later, their company sought bankruptcy protection, owing $2.1 million to creditors. The venture continued for a few years.

Alan Garten, Mr. Trump's in-house counsel, said that executives were unaware of the Milins' history when their business relationship began but that he could not recall when they became aware of the couple's run-ins with regulators.

Operating as the Trump Institute, the Milins pursued familiar tactics — and attracted familiar complaints, eventually earning an F from the Better Business Bureau.

Seminar attendees who later sought assistance from supposed experts over a Trump Institute toll-free phone line complained of being told to ignore what they had been taught in the seminars because it was outdated or useless advice. "The 'advisers' refused to listen to us when we referred to the methods taught in the seminars," Fred and Zofia Besel, a retired couple from New York, wrote in 2009, seeking a refund in a letter that wound up with the Florida attorney general's office.

Unbeknownst to customers at the time, though, even the printed materials handed out to seminar attendees were based on a lie. The Trump Institute copyrighted its publication, each page emblazoned with "Billionaire's Road Map to Success," and it distributed the materials to those who attended the seminars.

Yet much of the handbook's contents were lifted without attribution from an obscure how-to guide published by Success magazine in 1995 called "Real Estate Mastery System."

At least 20 pages of the Trump Institute book were copied entirely or in large part from "Real Estate Mastery System." Even some of its hypothetical scenarios — "Seller A is asking $80,000 for a single-family residence" — were repeated verbatim.

Asked about the plagiarism, which was discovered by the Democratic "super PAC" American Bridge, the editor of the Trump Institute publication, Susan G. Parker, denied responsibility and suggested that a lawyer for the Milins, who provided her with background material for the book, might have been to blame.

The lawyer, Peter Hoppenfeld, who no longer represents the Milins, said Ms. Parker was likely at fault but acknowledged forwarding her information from the Milins' office. Reached at her home in Boca Raton, Fla., Irene Milin told a reporter, "I'm very busy," and hung up. She did not answer subsequent calls or respond to a voice mail message.

Mr. Garten said Mr. Trump was "obviously" not aware of the plagiarism. But even while playing down Mr. Trump's link to the Trump Institute, calling it a "short-term licensing deal," Mr. Garten expressed pride in the venture. "I stand by the curriculum that was taught at both Trump University and Trump Institute," he said.

Ms. Parker, a lawyer and legal writer in Briarcliff Manor, N.Y., said that far from being handpicked by Mr. Trump, she had been hired to write the book after responding to a Craigslist ad. She said she never spoke to Mr. Trump, let alone received guidance from him on what to write. She said she drew on her own knowledge of real estate and a speed-reading of Mr. Trump's books.

Ms. Parker said she did venture to one of the Trump Institute seminars — and was appalled: The speakers came off like used-car salesmen, she said, and their advice was nothing but banalities. "It was like I was in sleaze America," she said. "It was all smoke and mirrors."