It's not just the least-paid workers who will be seeing higher incomes after the latest round of minimum wage hikes.

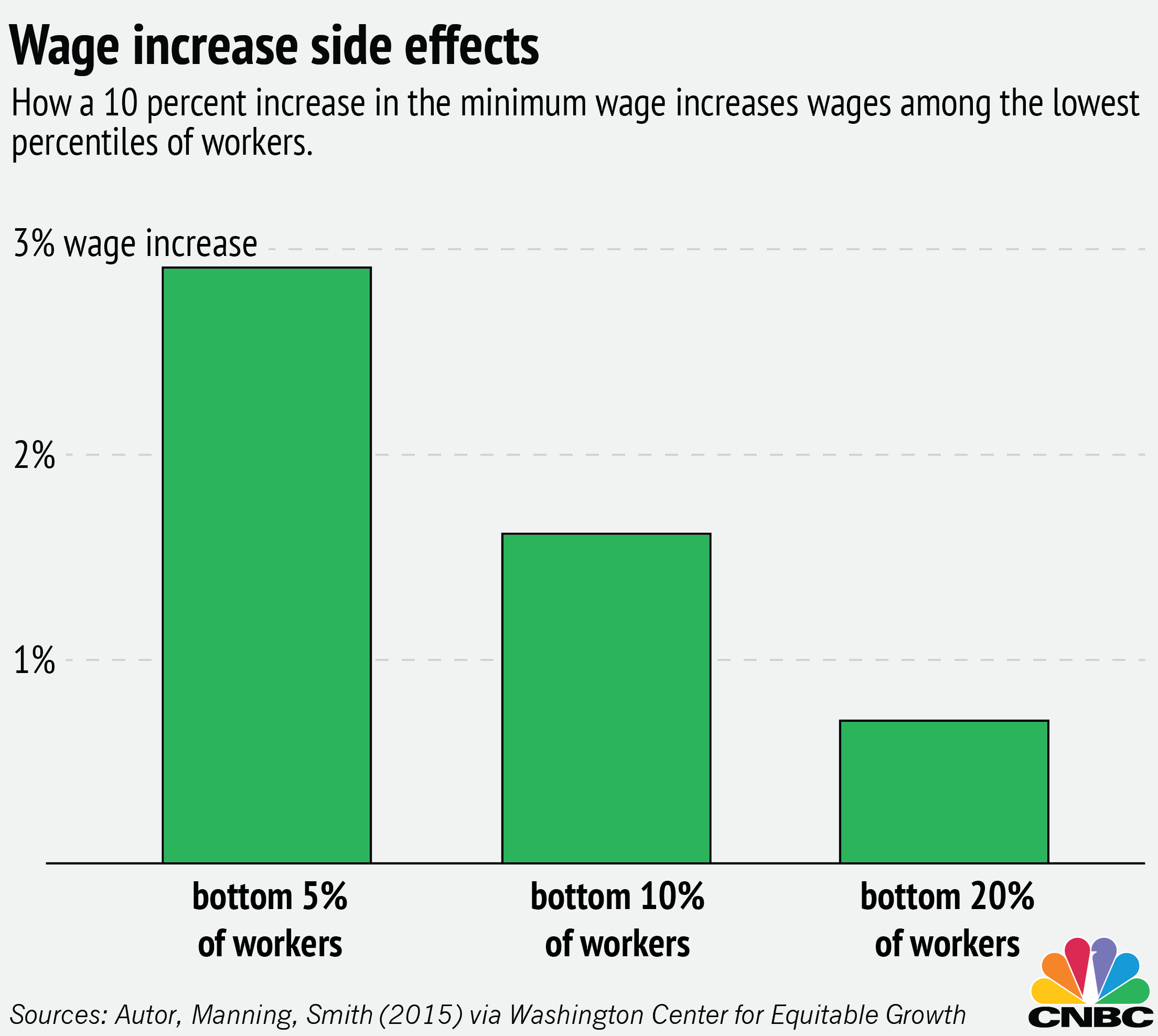

More than a dozen cities and states raised wages this year, and those higher pay floors should also cause a ripple of extra earnings for people making as much as 20 percent more than the minimum, according to economists. For states like New York and California, which will increase wages to $15 an hour over the next few years, those benefits will extend to people making $18 an hour, according to some estimates.

Indeed, in the June jobs report released Friday, wage growth hit 2.6 percent for the past year, the highest level since the Great Recession. What's more, the data showed that 287,000 jobs were added in June, far exceeding analysts' expectations. Even if future job growth should slow, some believe that is still good for wages.

Wage increases above the minimum wage are believed to be a response to what economists call "wage compression," which occurs when more senior employees are no longer better compensated than less senior employees.

Say you worked at a fast food restaurant in Washington, D.C., at the old local minimum of $10.50. On July 1, your hourly wage increased to $11.50. That's great news for you, but the shift manager getting paid $12 an hour may not be overjoyed about your sudden good fortune.

In the old economic models, the workers don't care what the employees next to them are making, said John Schmitt, research director at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth. But in reality, we compare our pay to the pay of the people around us.

"We know, however, from extensive experience and reflection on our own lives that if somebody who just finished high school and has no experience is making the same amount as someone with more experience, you have a real-world problem recruiting and retaining people and motivating them to work," he said.