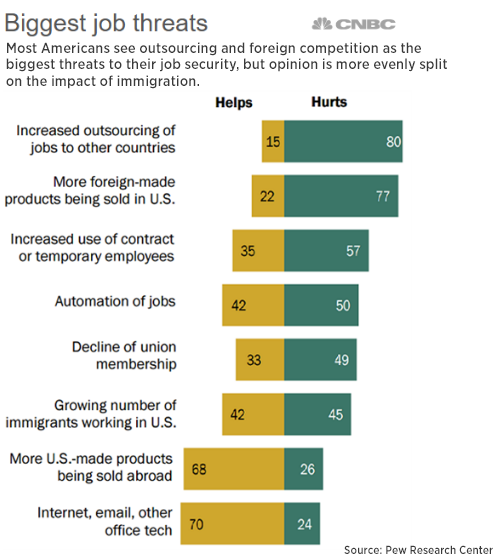

American workers believe the forces of globalization are the biggest threat to their paychecks, but they're much less worried about the impact of immigration on job security.

Those are among the findings of a comprehensive study of changing attitudes in the modern workplace and the forces that have brought dramatic changes to the working lives of Americans.

The study, released Thursday by the Pew Research Center and the Markle Foundation, is based on decades of government data and survey results with some 5,000 Americans.

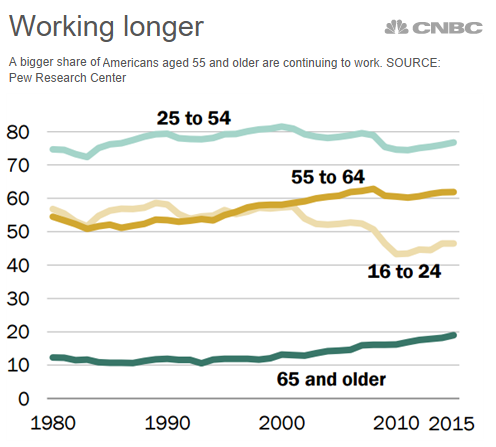

The results show an increasing demand for more highly skilled workers, a trend that many workers say will require them to continue their education and training throughout their careers. And the majority of those surveyed said the responsibility for getting that training lies with individual workers — more than government, employers or schools.

Attitudes about the impact of globalization were mixed. While the study found that workers most fear outsourcing of work to foreign countries, they also believe boosting exports of U.S. goods helps American workers.

The survey respondents said that other major threats to U.S. workers included greater reliance on contract and temporary work and the decline in union membership.