"It sucks," says Mike Mayo. One of the more visible Wall Street analysts, Mr Mayo lost his job last week when CLSA, the Chinese-owned broker which had employed him, abruptly shuttered its US research operations.

At 4.15pm last Monday, as Mr Mayo tells it, he was summoned to an all-hands meeting. At 4.20pm he and 89 others were let go. He went to FedEx to buy nine boxes and by 9pm that evening he and his belongings left the building for good.

CLSA blamed "the economics of providing US equity research [becoming] increasingly challenged". It is a perfectly plausible explanation. Active managers are performing badly and looking to cut costs rather than pay for research. Regulations have hit the business.

More from Financial Times:

Oil price cracks as market focuses on rising production

Divisions in anti-Le Pen front open a narrow path to victory

Azerbaijan watchdog suspension puts gas pipeline loans at risk

The number of analysts working at the world's 12 biggest investment banks fell to 5,981 last year, according to numbers from Coalition, a data provider on the industry. That is down from 6,282 at the end of 2015.

At the same time that Mr Mayo was losing his job, another analyst covering the banking sector also suffered the same fate. Paul Miller, who worked until Wednesday at FBR Capital Markets, is more pessimistic on the future of the industry: "There's just not a lot of money in sell-side research for [independent] broker-dealers any more because the bulge brackets give it away and it's a loss leader for them. I've seen this coming and I've been preparing." Mr Miller, 55, plans to take some time off and plot his next move.

Some analysts have always been attracted to the adjacent world of investment banking. Imran Khan was an analyst at JPMorgan six years ago, moved to Credit Suisse as an investment banker and later joined the tech industry. Last week he was at the New York Stock Exchange for the initial public offering of Snap, where he is chief strategy officer. Mr Khan's stake in the messaging app is worth about $200m.

Not everyone sees research as a dying industry.

The day after he was made redundant, Mr Mayo attended JPMorgan Chase's annual investor day as usual, where he introduced himself as a "free agent analyst". Jamie Dimon, JPMorgan chief executive, launched into a story about arriving to run a previous bank and discovering that Mr Mayo had been banned by staff from analyst calls. "And they said, 'well, he was terribly insulting . . . because he's written, literally, a tome' and it was called, 'Even Hercules Can't Fix It'. And it went through the bad systems, the bad credit, the inefficiencies and stuff like that. I told the management team, 'I hate to tell you, read his tome, because he's right about every single thing in there'."

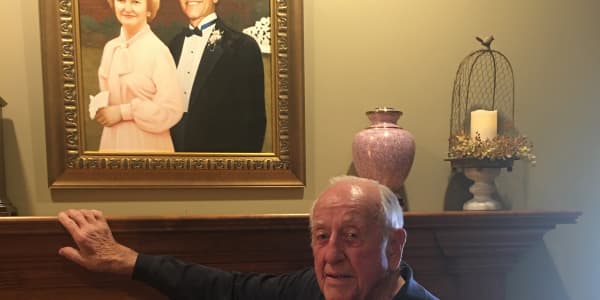

Mr Mayo shares Mr Dimon's confidence in Mr Mayo. A habitual sceptic, he turned bullish on banks in February last year before a big rally. "I shouldn't be in this position. I had the best professional year of my life," he says. He went a bit further in a New York Post profile, comparing himself to Cézanne. ("We didn't know whether to laugh or cry," says a fellow analyst of that analogy.)

CLSA may have failed to find a sustainable business model but that is not an inevitable fate. Autonomous Research, founded in London by Stuart Graham, a former banks analyst at Merrill Lynch, set itself up as a research-only institution in 2009 and has made it pay. Now, as forthcoming European rules force an unbundling of research and trading, other firms will have to move in the same direction. "When we started, it certainly felt unique," says Mr Graham. "Eight years ago no one was putting a price on research; from January 2018 everyone in Europe will have to put a hard dollar number on it. There will be a shrinking pie and a significant reallocation of that pie. Boutiques will be winners from that reallocation."

Mr Graham's business looks to be doing fine. Accounts for the European division of the privately held company show revenues of £27.7m last year, out of which 30 partners shared £16m. That is good money on Wall Street today. Even if they have kept their jobs, some analysts say they earned $1m 10 years ago and now earn $250,000.

For his part Mr Mayo, irrepressible, says: "Investors are willing to pay for my research. I'm so charged up. I'll stop at nothing here."