That price appreciation is great news for web behemoths like Alphabet and Facebook, which control the lion's share of the digital advertising market. But it's a less sunny stat for the advertisers themselves, which are likely getting less for each dollar they spend, according to Adobe's analysis. Advertisers are paying more simply to keep their customer bases while engaging in fierce competition over new customers.

"We're no longer in a period where you can just get organic growth," said Tamara Gaffney, principal analyst at Adobe Digital Insights. "Now it's a dog-eat-dog competitive world."

U.S. spending on digital advertisements is expected to hit $83 billion this year, surpassing total TV ad spending for the first time, according to a recent forecast by eMarketer. The majority of that revenue is expected to go straight to Google and Facebook, which accounted for nearly all of the growth in ad sales last year.

Google dominates the search market, while Facebook is stronger in display. Both companies have made strides in mobile and video. Mobile accounted for 83 percent of Facebook's ad revenue last year, compared with 77 percent in 2015, according to the company's filings. For Google, mobile ads are about half of the company's ad revenue.

The companies themselves report a number of different per ad revenue metrics. Facebook's "average price per ad" measure increased by 5 percent last year and 140 percent the year before. In contrast, Google's "aggregate cost-per-click" across the segment fell by 11 percent in both 2016 and 2015, a decline the company attributed to "continued growth in YouTube engagement ads where cost-per-click remains lower than on our other advertising platforms." (Adobe's data includes billions of TV-everywhere views, but not YouTube).

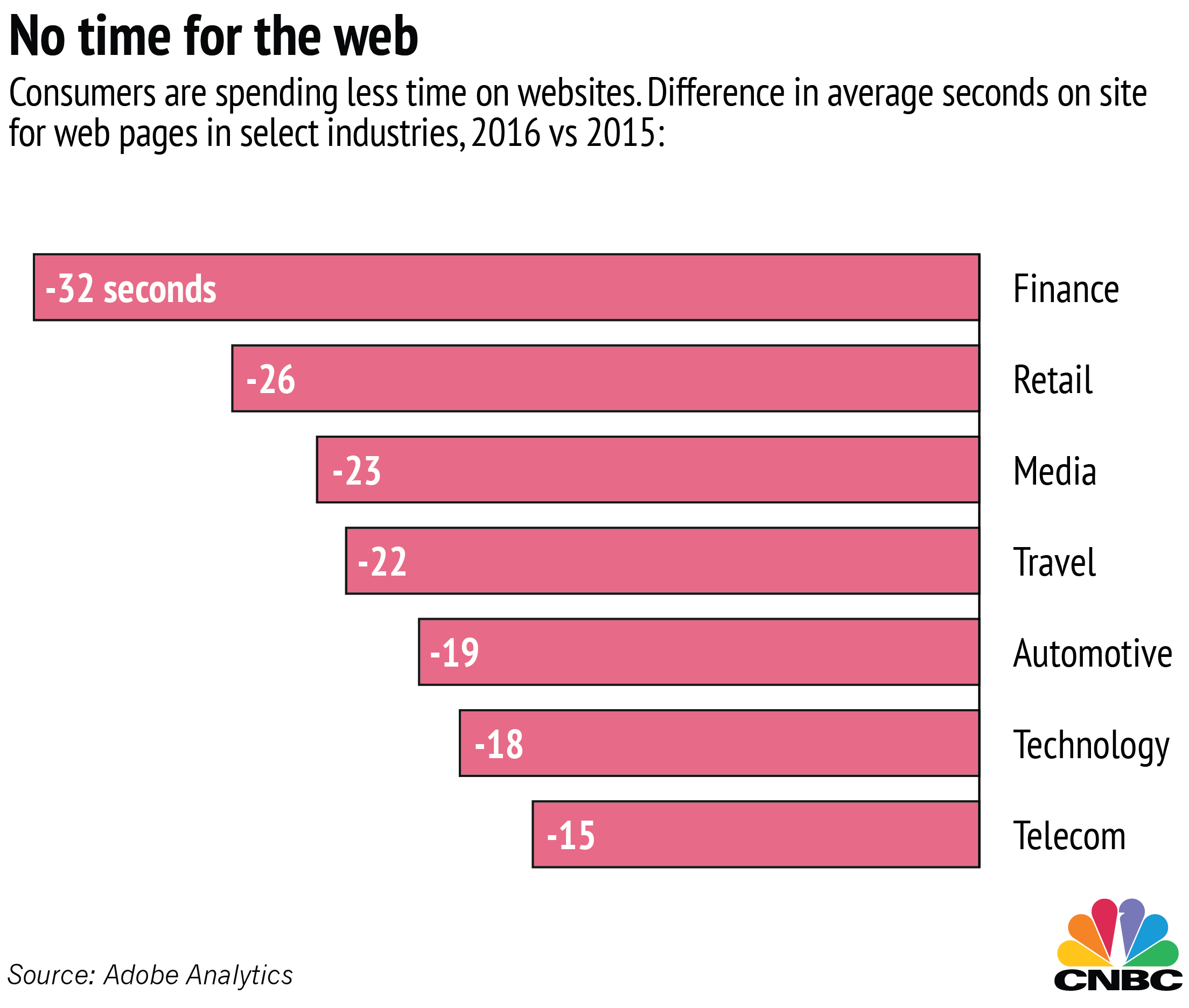

"The majority of the digital ad spend is in search and the majority is going to one company," said Gaffney, referring to Google. "That company is getting a lot, but the ability to translate into more people coming to a site is getting harder and harder, and then when they get to the site, they don't stay as long."