The continuing nuclear threats from North Korea are now starting to raise fears of a real and bloody conflict with a rogue regime. But there's an historically proven way to resolve the worst of this threat without firing a shot.

Here's how: North Korea and its one key backer, China, essentially want the same thing. That would be a reduced U.S. presence in East Asia and in their nations' affairs. This is something they've wanted for years.

While North Korea's missile tests and threats understandably grab the headlines, China has also made several moves in recent years in hopes of scaring off or at least diminishing America's longstanding military footprint in the region. And every time the U.S. goes to Beijing and asks for its cooperation to tamp down North Korea's missile firing threats, it's one less time that the Trump team is pounding the Chinese on currency manipulation, protectionism, and its own adventurism in the South China Sea.

In essence, China is and has been using North Korea like a burly bouncer at a dance club it currently shares with Japan and South Korea. That doesn't mean it completely approves of every single move Kim Jong Un and company execute out of Pyongyang. But there is general agreement from across the political spectrum that Beijing has been using North Korea for decades in hopes of advancing its regional goals.

Despite the complexity of the problem, the solution for the U.S. is remarkably simple. If North Korea and China are acting in a dangerous and unlawful way to get the U.S. to somehow stand down in Asia, the proper response isn't to launch an attack, but to simply show up even more.

We can look to the final years of the Cold War as a model for success.

It's important to use those Cold War lessons because the false choice we're hearing today on the North Korean threat is eerily similar to what we were told during the U.S. conflict with the Soviet Union. That would be the insistence that the only two choices are war or major concessions to the aggressors.

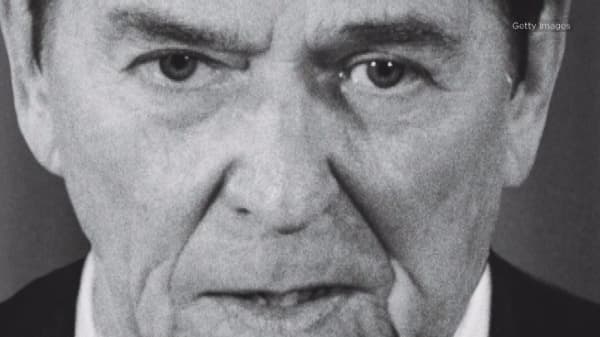

That wasn't true then, and it isn't true now because the Cold War was eventually won by the U.S. and the West without launching a major attack in its final 10 years. And the way the U.S. won it then was by following President Ronald Reagan's clear and unwavering policy of showing up.

Showing up in the 1981-91 era meant increasing NATO's missile defense and offensive missile presence along the borders with Eastern Europe and even into outer space, boosting the size and scope of the U.S. Air Force and Navy, and not agreeing to back down until a very tangible concession on Soviet nuclear arms was in hand.

President Reagan's domestic political opponents and pro-Soviet propaganda outfits attacked this strategy in full force. The prevailing message was that the Reagan policies of building up our forces, even if no attacks took place, put the world too much at risk for a nuclear confrontation. The media became flooded with nuclear doomsday warnings and dramatizations, hitting their zenith with the 1983 TV movie "The Day After" that posted record high ratings.

Even President Reagan himself said the program left him "greatly depressed."

But depressed or not, Reagan stayed the course. And thanks to unwavering support from Great Britain's then-Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, the Soviet Union realized it could not simply scare the U.S. out of defending Western Europe and could not scare Western Europe into urging the U.S. to stand down.

Despite numerous depictions of Reagan and the U.S. in general as being eager for war, the Pentagon knew there was no good option for any direct attack on the Soviet Union. Showing strength , not using it, was the goal. And after only a decade of the U.S. executing that policy, a nearly 50-year-long Cold War ended when the U.S.S.R. ceased to exist in 1991.

There are many parallels to the Cold War scenario in our current situation, but the key similarities are that China and North Korea want to get the large American military presence out of a particular region, the U.S. has a potential Thatcher-like ally in Japan's Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his administration, and there's also at least very good potential that an increased U.S. military presence in the region will convince everyone that this North Korean missile gambit has backfired badly.

Of course, there are still great risks involved. Unlike Japan, South Korea is decidedly not playing the staunch ally role right now. It doesn't always appear resolute in the face of the threats from Pyongyang for a number of understandable reasons. As its neighboring country, it stands to be the biggest loser if Kim Jong Un decides to lash out or retaliate to perceived U.S. aggression. And don't forget that millions of South Koreans still have families above the 38th Parallel, making them less eager for any kind of military attack on North Korea.

There is no way to completely eliminate risk when dealing with a nuclear armed dictator like Kim Jong Un. That's why the "option" of a straight attack on the regime isn't a good one. Yet diplomacy and sanctions alone won't necessarily reduce the threat.

North Korea is surely a bigger problem now than it was in 1994 when the Clinton Administration made the deal it thought would stop it from becoming a nuclear power. That doesn't mean diplomacy isn't an option, but the U.S. has to do something else first.

And that thing is to once again show increased strength. The U.S. must continue to show up in East Asia with our huge naval and air bases and the 37,500 troops we have stationed in South Korea alone.

It must at least prepare to increase that presence with more naval ships, more anti-missile batteries like the THAAD system, and more fighter and bomber jets stationed in the area. Our allies in the region need to get behind this plan too. Once that new presence is established, the American, Japanese, and South Korean negotiating position will be a lot better than it is now.

China and North Korea must be shown that their goals cannot be achieved via military aggression. The only way to do that is not just to refuse to give them what they want, but also refuse to accept the notion that the only result of standing up to these regimes is war.

Commentary by Jake Novak, CNBC.com senior columnist. Follow him on Twitter @jakejakeny.

For more insight from CNBC contributors, follow @CNBCopinion on Twitter.