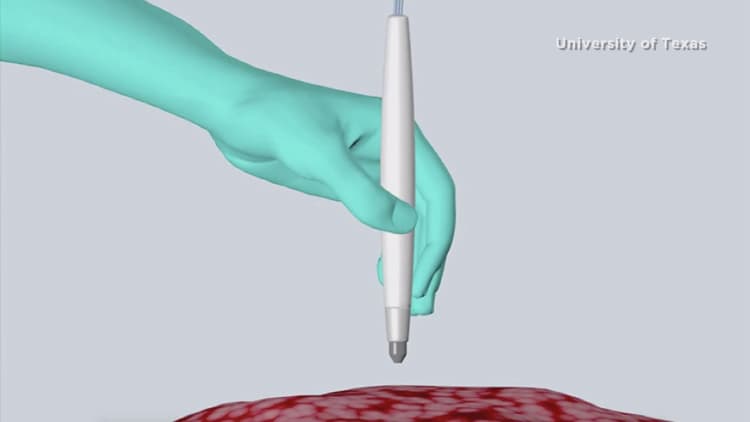

Scientists at the University of Texas say they have invented a handheld tool can identify cancerous tissue in 10 seconds.

They say, the new "MasSpec Pen" speeds the testing process by as much as 150 times and should make the surgery to remove a tumour more accurate.

"If you talk to cancer patients after surgery, one of the first things many will say is 'I hope the surgeon got all the cancer out,' " said Livia Schiavinato Eberlin, an assistant professor of chemistry at UT Austin who designed the study and led the team.

"It's just heartbreaking when that's not the case. But our technology could vastly improve the odds that surgeons really do remove every last trace of cancer during surgery," Eberlin added on the university's website on Wednesday.

The study's abstract said tests taken from 253 human cancer patients took about 10 seconds and were shown to be accurate 96 percent of the time.

The tests included tissue related to breast, lung, thyroid and ovarian cancers.

How it works

The scientists explained that each type of cancer has its own molecular structure that acts as a "fingerprint."

When the "MasSpec Pen" is placed onto suspect tissue, a drop of water is released which absorbs molecules.

The pen then drives the now tainted water into a much larger machine known as a mass spectrometer which analyses the molecules and offers an assessment of whether cancer exists.

When the MasSpec Pen completes the analysis, the words "Normal" or "Cancer" automatically appear on a computer screen.

For certain cancers, such as lung cancer, the name of a subtype might also appear.

"Any time we can offer the patient a more precise surgery, a quicker surgery or a safer surgery, that's something we want to do," said James Suliburk, head of endocrine surgery at Baylor College of Medicine and a collaborator on the project.

"This technology does all three. It allows us to be much more precise in what tissue we remove and what we leave behind."

The pen is now awaiting full approval and scientists behind the technology have filed U.S. patent applications.