Kevin Warsh, front-runner to be Fed chairman, has not been shy about his desire to shake up the central bank and turn it into a more hands-off institution with clearer policy rules.

The one-time Federal Reserve governor is seen as someone who would respect the Fed's independence but change how it views policy, in a dramatic enough way to please some of the institution's many critics in Washington. Warsh himself has been a critic of the Fed for years, complaining that after it rescued the economy, it continued to pursue extraordinary easing policies to the detriment of the markets and economy.

"It's a regime change," said Diane Swonk, CEO of DS Economics, who has known Warsh for years. "He's been very vocal about what he thinks is wrong and what he would do differently."

Swonk said not since the Great Depression has a president had the opportunity to remake the composition of the Federal Reserve Board, with four open seats, and if Warsh were to head the central bank, it ultimately could be a starkly different institution. He would be the first chairman not to hold a doctorate in economics since Paul Volcker.

would most likely favor less regulation of the banking system, something President Donald Trump favors. From a policy standpoint, he may de-emphasize the Fed's reliance on its inflation target as a guide for interest rate hikes, something that's been frustrating for the Fed and periodically perplexing for markets. He also is expected to be than Fed Chair Janet Yellen and could encourage a more rapid unwinding of the massive Fed balance sheet, which it has only begun to whittle back.

Warsh has not been shy about calling out what has been conventional thinking.

"Virtually all guilds have a certain kind of groupthink. The economics profession is not immune to that," Warsh said in a 2015 interview on CNBC. "What troubles me is we don't call attention to the way the groupthink can be wrong."

The 47-year-old former banker proved during the financial crisis to be very capable of explaining the Fed's high-level policy debates in a pragmatic way to policymakers, something that could be important to Trump. Warsh worked closely with former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke on the Fed's financial crisis policy, and he was the one who got to explain it to politicians.

"He had that practical side to him that allowed him to be a great ambassador for Chairman Bernanke at the time. Bernanke was doing his own thing, meeting with [Treasury Secretary Hank] Paulson but Kevin Warsh had a specific role to talk to the policymakers and the financial markets," said Daniel Clifton, head of policy strategy at Strategas. That also included speaking to President George W. Bush, for whom he had served as economic advisor for four years in the White House.

"Here's a guy who briefed the president of the United States day after day as a White House employee. He knows exactly how to talk to the president. People at the Fed didn't know how to talk to policymakers like he did," said Clifton.

Warsh is already known to Trump, who may be more comfortable with the charming former Wall Street banker than with Yellen, whose term ends early next year. Warsh worked for seven years at Morgan Stanley before joining the Bush White House in 2002 as an economic advisor.

Four years later, he was named to the Fed at age 35, making him the youngest Fed governor ever. He served until 2011. To Fed insiders, his background during the financial crisis could give him more credibility and also the ability to challenge the norm, such as some of the economic models used by the central bank.

Warsh has something else going for him that could help him with the president. His wife is the granddaughter of Estee Lauder, and her father, Ronald Lauder, is a long-time close Trump friend.

Warsh, a fellow at the Hoover Institution, was also a member of Trump's now-disbanded, a group made up mainly of CEOs who were working with the White House on economic and policy issues. A source close to that group says Warsh's comments during its meetings were measured and authoritative.

"He basically talked about risks in the economy in a way that would be meaningful to a president," said the source, referring to the forum's gatherings, whose participants included Trump. "He knew how to integrate markets and policy and spoke with clarity and authority but also basically respect. He was not heavy-handed about it."

Warsh has other attributes that would appeal to the president.

Unlike Yellen, he is seen as someone who would favor the kind of financial deregulation Trump supports. On the other hand, while Trump likes low interest rates, Warsh could lean toward more hawkish policies, since he believes the Fed has been too slow to end its easy ways.

"Financial markets and the Treasury market are telling us almost nothing about the state of the economy because central banks are influencing those prices with every word, with every nuanced speech from every reserve bank president," Warsh said in the 2015 interview on CNBC. "We would be better off if markets were setting prices instead of taking their lead from a bunch of government officials seven years into a U.S. economic recovery."

In a Wall Street Journal op-ed earlier this year, Warsh suggested lowering the Fed's inflation target to 1 to 2 percent, from its current 2 percent. The current pace of about 1.4 percent would fall within that range and encourage Fed officials to raise interest rates.

Warsh argued for a "trend dependence" instead of "data dependence," the Fed's current strategy. "When the broader trends begin to turn — for example, in labor markets or output — the Fed should take account of the new prevailing signal," he wrote.

More recently, Warsh gave a speech in May at Stanford University for the Hoover Institution. Some see that speech as a blueprint for how he would rebuild the Fed, discussing the need for change there.

"The central bank and the academic community should engage in a fundamental rethinking of the Fed's strategy, tools, governance, and communications," he said. "A reform agenda could improve the modal outlook for the U.S. economy by clarifying the Fed's responsibilities, improving its decision-making, and bolstering its credibility."

Warsh has also commented frequently on the fact that the Fed over time changed the way it would end quantitative easing, which was expected to be a scaling back of the balance sheet even before it raised rates.

"This strikes me as quite inconsistent with the original ideas of what QE would be," he said in the 2015 interview with CNBC. "Secondly, I would say interest rates need to be set in financial markets, and interest rates are not set in financial markets when the Federal Reserve and the world's other central banks are the buyers of first and last resort."

Swonk said Warsh and a new group of Fed governors would take some time to transform the Federal Reserve, but it would be different and have significant market implications.

"He would possibly look at the balance sheet. Other people they're interviewing are on the same page. You're talking about more aggressive balance sheet reductions, which means a very different environment than we've had in the past. ... It will be very different than the gradualism we are used to," she said.

Despite Warsh's relationship with the president, Fed watchers and policy strategists do not believe Warsh would put politics before the Fed's reputation for independence.

"I think he's smart enough to know that if there's a perception he was politicized, it would hurt the Fed's credibility, so I can't believe he would encourage any perception he was Trump's puppet," said Greg Valliere, chief global strategist at Horizon Investment.

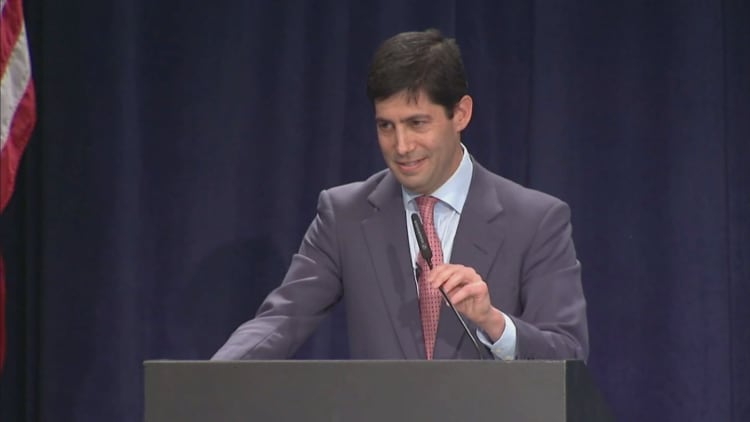

WATCH: Kevin Warsh: Central bank is a 'slave' to the stock market