The arrival of Diana Henriques' new book, "A First-Class Catastrophe: The Road to Black Monday, the Worst Day in Wall Street History," could hardly have been more timely.

On the eve of the 30th anniversary of Oct. 19, 1987, the largest single-day sell-off ever, the Dow Jones industrial average closed above 23,000 basis points for the very first time. Optimism and confidence abound for the future of the record bull market. Technologies and products — everything from high-frequency trading software to the rise of ETFs — are changing the nature of investing in ways not always immediately clear. And the regulators in charge of keeping these moving parts aligned are even more diffuse and fragmented than they were three decades ago.

What you say, how you say it can be the difference between a 100-point drop and a 1,000-point drop.Diana HenriquesAuthor, "A First-Class Catastrophe"

Henriques, an investigative reporter and author of the bestselling book and recent HBO film adaptation "The Wizard of Lies," about convicted swindler Bernard Madoff, shared both her research and her concerns with CNBC on Wednesday. The conversation is presented below, with minor edits for clarity.

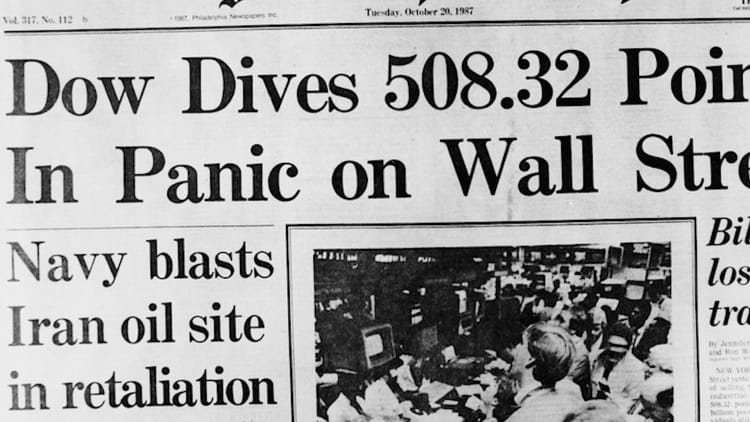

For those who have never heard of it before – what was Black Monday?

Black Monday was the worst single day in stock market history. On that day, the Dow Jones industrial average fell 22.6 percent. Now, that was worse than the worst day of 1929; it was worse than anything in the 2008 financial crisis. It's worse than any day we've had in stock market history. And it came after two really, really bad weeks in the stock market before that.

But besides being an occasion when the stock market fell, it was also a triggering event that almost caused the stock market to fall apart. The avalanche of selling, using computer-driven order delivery systems, almost overwhelmed the marketplace as it existed at that time.

The reason it's so fascinating to me, and why I think it matters so much, is it reflected in one horrible day all of the profoundly important changes that had been occurring in the stock market in the years leading up to Black Monday.

The average person seems to know either nothing or very little about Black Monday. Why has it been largely forgotten by the general public, compared with, say, the Great Depression?

Well, certainly, 1929 is better known. We study that in our history books. And 2008 is better known because we experienced that in real life. So 1987 kind of falls in that shadowy area between current events and history. I think another reason is that we're trained to think of stock market movements in calendar years. And if you actually look at the calendar and the Dow at the beginning of January 1987 and at the end of December 1987, it looks pretty tame. It ended the year within an eyelash of where it started.

I thought Gary Cohn would have been a logical, calm voice from the cockpit. But now... I'm not sure he's going to be in place for very long.Diana HenriquesAuthor, "A First-Class Catastrophe"

But that's sort of like saying, 'Well, I got off the roller coaster at the same place I got on the roller coaster, so nothing really happened,' you know? In fact, the market soared up 40 percent, plummeted down all the way to December before bottoming out, and it remained turbulent and unpredictable and gyrating wildly for months and months. And it took two years to get back up to its August peak. So we have this kind of foggy memory of 1987 as not being a terrible year in the market — that's part of the reason it's been forgotten.

Another part of the reason is, it did not lead to a serious recession. And the financial crises that we tend to remember are the ones that then rippled out and cratered the real economy — not just the financial markets, but the real economy. So that didn't happen in '87. Some market crashes are important because of what came after, like '29 and '08. But some market crashes are important because of what they showed us at the time, and that's why I think '87 is so important, but it kind of falls into the shadows between history and current events.

It seems that one of the root causes of the crash was an unprecedented intertwining of different parts of the stock market – hastened by new products such as financial futures. Has this trend slowed or accelerated since 1987?

Accelerated. You're absolutely right that what was happening since the '80s, almost without us realizing it, was what had previously been thought of as independent markets — for stocks, bonds, currency derivatives — were being shackled together, in part by new financial derivatives and in part by new financial trading strategies that used those new derivatives in new ways. So portfolio insurance was one such hedging strategy. Index arbitrage was another such strategy. But these new derivatives being used in new ways by giant-sized, really super-sized investors, were a genuinely new thing in the 1980s. It took a long time for regulators to realize what was happening, and then even after Black Monday it was very hard to figure out what to do in response.

There was a prescient quote in the book from "market guru" Joe Granville, who said of then-novel stock index futures: "Now, instead of betting on a stock, you can bet on the entire market. It will tell me how the people feel about the future of the market." Is there a parallel between the optimism then and now?

Granville's quote is so much fun, in part because he saw instantly what a speculative tool these new derivatives could be. Now, they have a legitimate purpose: They genuinely can be used to offset market positions by institutional investors. No argument there; they are a useful tool. I'm not saying we should blow them up.

I'm deeply concerned about the fact that we still have the same fragmented, balkanized regulatory system that was identified after Black Monday as one of the biggest problems we needed to fix.Diana HenriquesAuthor, "A First-Class Catastrophe"

But they do have effects, and one of those is to provide people with a way to speculate in the stock market with a lot more leverage and a lot less skin in the game. And that massive increase in leverage was one of the things that regulators totally missed. And yet, that remains one of the chronic problems in our market in 2008 and up to today: New products that allow people to use a little bit of money to take a great big bet. That's what the markets were struggling to cope with back then.

Why was Black Monday so much more severe than any crash before or since?

Well, there's no easy answer to that that doesn't just come down to human panic. The markets were interconnected in ways that were frightening and new. Human beings don't do frightening and new very well. People who thought they knew how the markets worked were suddenly confronted with a reality that looked starkly different — frighteningly different — and that fed old-fashioned panic.

Now, we've had panics before. They've tended to stay within the markets where they occurred. 1929, the worst days of that crash were a panic. 1907, we had a massive stock market panic. It's not a new phenomenon, and neither is it an obsolete phenomenon. Human emotions still play an enormous role in how our financial markets behave, as Richard Thaler so wonderfully showed in the research that led to him receiving the Nobel Memorial Prize in economics.

So, why was Black Monday so bad? In part, it was because the market systems were strained almost to the point of breaking. They couldn't cope with this avalanche of selling. And partly, it was because of the fear that was sparked by a sudden awareness that the markets were not behaving normally. You couldn't use the markets the way you long thought you could.

Could this happen again, and do you think it might happen soon?

Well, obviously it could happen again. There's been no repeal of the market cycle. There's been no repeal of human nature. So clearly, markets are going to go up and down, and if they go down in a precipitous manner that escapes the control of smart regulators, we could have another crisis.

I wish I could say I am more optimistic. I'm deeply concerned about the fact that we still have the same fragmented, balkanized regulatory system that was identified after Black Monday as one of the biggest problems we needed to fix. It was identified again after 2008 as one of the biggest problems we needed to fix. And yet here we are in 2017, and we still have this balkanized regulatory system where one agency regulates these people and another agency regulates that product and a bunch of different regulators regulate other things.

You know, we've got a banking supervisor, a securities supervisor and an insurance regulator in every one of the 50 states? So that's 150 regulators to start with before we even get to Washington. Multiple banking regulators, a stock market regulator that only regulates the stocks and the options, and a different regulator that regulates options on futures and futures contracts and has recently been put in charge of certain aspects of swap which did us so much damage in 2008. So if anything, our regulatory system is even more fragmented now than it was on the eve of Black Monday.

And the political situation is such that I have a deep concern about how Washington would respond to another crisis. In 2008, at least Hank Paulsen and Ben Bernanke knew each other. They had been in their jobs for a while, and Paulsen came straight out of Wall Street. Looking at the team you would expect to be the first responders in a crisis in the next six months, a year, two years — I don't even know who it would be. I'm concerned about an apparent lack of sensitivity to how much the message matters in the middle of a market meltdown.

What you say, how you say it can be the difference between a 100-point drop and a 1,000-point drop. Message management in Washington and regulatory fragmentation in Washington are, to me, the two things that I worry most about.

I think that's a pretty reasonable fear.

Well, you know, I thought Gary Cohn would have been a logical, calm voice from the cockpit. But now most of Wall Street thinks he doesn't have Trump's ear, and I'm not sure he's going to be in place for very long. No one knows how long Janet Yellen's grasp on her position is, or who will fill her shoes if she leaves.

Jay Clayton is a totally unknown regulator, zero experience as a regulator before, not unlike the SEC chairman at the time on Black Monday, who had been a securities regulator for all of 10 weeks when Black Monday occurred. Fortunately, he was able to learn on the job, but he would tell you he made some mistakes. Steve Mnuchin, as the Treasury Secretary, logically would be a point man — in fact, his father played an important cameo role in helping pull us back from the precipice on Black Monday and Tuesday. Robert Mnuchin — you can find him in the index of the book — that's Steve Mnuchin's father.

But some of the messaging that's gone out around legislative initiatives has been worrisome. To even suggest that congressional failure to pass one bill or another, or congressional failure to endorse the White House legislative agenda — to even suggest that a congressional failure like that would precipitate a market meltdown, I think is irresponsible. And yet, we have statements like that out of the administration in very recent days.

So I'm watching for a more sober, measured, well-informed response. That's what it took in '87 to calm us down. John Phelan gets in front of a bunch of microphones, and he sounds so calm, and he's so well-informed, and he seems to have a total grasp of what's going on. And it helped! It mattered that he was there, that he could step into that role. Someone's going to need to step into those shoes again in the next financial crisis — the shoes that Hank Paulsen and Ben Bernanke wore in 2008. And I think it would behoove us all to think about who that candidate would be.

WATCH: How did Wall Street miss the market cracks before 1987 crash? Here's how