Goldman Sachs traders lost $180 million last year on bad bets in natural gas markets, helping cause the worst commodities trading performance in the bank's history as a public company.

The bank, a powerhouse in commodities trading for decades, had positioned itself to profit from volatility in natural gas prices that never materialized, according to people with knowledge of the situation. At rival firm Morgan Stanley, power and gas traders led by rising star Jay Rubenstein generated almost $400 million in revenue for the bank last year.

The big narrative out of Wall Street after the financial crisis was that thanks to regulations and the rise of computerized trading, newly chastened human traders were no longer able to place big bets, capping their status and compensation. This is mostly true. But pockets of big risk-taking have persisted within the banks — and that could jump with last week's proposed changes to the Volcker Rule.

Given new rules that broadly switch the stance on trades from a presumption of guilt to a presumption of innocence, traders and their overseers will be more comfortable taking bigger amounts of risk than under the current Volcker Rule, said sources on trading desks. With the prospect of market volatility returning after years of calm, a lower regulatory hurdle could come at exactly the right time for bank traders.

Goldman and Morgan Stanley, both based in New York, are seen as most likely to take advantage of trading opportunities across their fixed income, commodities and equities trading businesses, according to the sources. Charlotte, North Carolina-based Bank of America and London-based Barclays may take more risk in areas including distressed debt and equities, they said.

The upshot: the odds that Wall Street traders can make a killing – or get killed – in the markets are about to increase.

Facilitate markets

The banks are adamant that these and other trades are done to facilitate markets. Nobody is claiming that any of the trades in this story violated the Volcker Rule. Furthermore, prudent risk-taking by banks can improve the liquidity of markets and act as moderators of price swings.

But the question of what kinds of trading banks should be doing is in play again since the Federal Reserve last week proposed changes to the Volcker Rule, which bans banks from engaging in purely speculative bets, or proprietary trading. The move is part of sweeping changes to banking regulation that critics say are overly burdensome on banks and hamper the functioning of some markets.

The trading rule, which was named after former Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, who originally proposed the regulation, was meant to prevent banks from acting as depositor-fueled hedge funds. It still had to allow them to make markets, or help clients buy and sell assets.

But the line between prop trading and making markets is blurry, since banks often need to step in and purchase assets that don't change hands often, in effect taking bets to help facilitate markets. So firms are allowed to engage in proprietary trading if they claim it's in anticipation of client demand — an important gray area that traders can use to make more lucrative bets.

Volcker 2.0

The changes, which are under a 60-day review period and dubbed Volcker 2.0, lift reporting burdens on short-term trades and replace a rule that traders only take positions in anticipation of near-term demand to giving banks leeway to set their own risk limits.

The wildly divergent results at Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley last year are an illustration of the risk-taking that already happens within the industry.

There are other examples. A Goldman Sachs junk trader named Thomas Malafronte generated more than $250 million in 2016 by taking huge positions in the debt of retailers and energy firms, Bloomberg reported at the time. This year, the bank's flow derivatives desk, run by David Casner, made $200 million in profit on a single day in February with positions in a volatility index.

A handful of senior traders at global investment banks have the ability, if an opportunity is identified and approved by risk committees, to be allowed much greater leeway to take directional bets, according to people with knowledge of the industry. Sometimes, only a small fraction of the original trade is offloaded to clients to justify the trade as market making, while the rest is held for gains, said the people.

The riskier, more lucrative bets are seen as helping keep trading desks open for clients, since pure market making has become less profitable amid relatively placid markets and tight spreads between what sellers and buyers will agree to.

"If you're a market maker and you don't take an opportunity to strap on risk when you see an asymmetric payoff, why are you paying a guy who can do that to not do that?" said a trader at a major Wall Street firm who declined to be identified speaking candidly. "You've got to use your information and expertise to do stuff like that occasionally when you have good risk-reward."

No return to pre-crisis levels

Even among critics of the Volcker proposal, few claim banks risk going back to the wild days of a decade ago when the industry's dizzy leverage meant that small drops in asset values could wipe firms out. All the other post-financial crisis limitations that banks are subject to, including rules on capital, leverage, liquidity and stress tests should prevent trading from getting out of hand.

The changes, which could be approved by five U.S. regulatory agencies by the end of this year, will make the most difference during the next financial crisis, J.P. Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon said last week during a conference.

"It might not be a big change now, but it probably will create more liquidity in bad times, which is when you really need it," Dimon said. "In bad times, you want market makers intermediating aggressively, standing in, giving you all a chance to buy and sell, modify your portfolios, adjust to inflows and outflows. And you needed that. A couple of banks did that aggressively in the crisis."

Coincidentally, that is also when traders stand to make the most money and biggest bonuses. Spreads tend to be the highest in turbulent times when hedge funds and asset managers are desperate to sell holdings. Goldman Sachs had its most trading profitable year in 2009, when it generated more than $30 billion.

When everyone else is selling, it's good to be the counterparty of last resort.

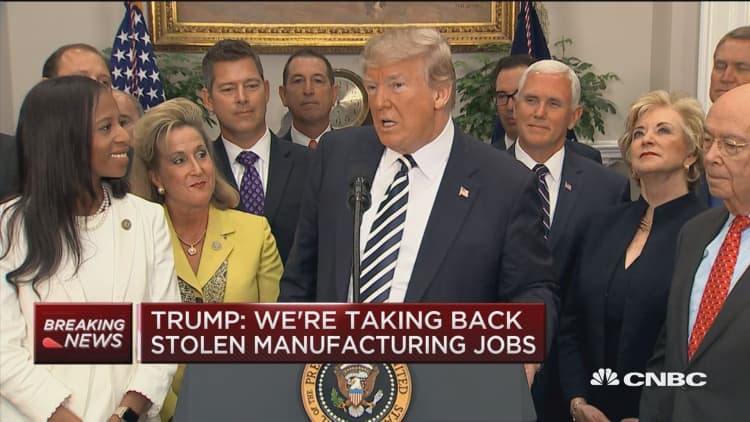

WATCH: Trump signs Dodd-Frank rollback