Venture capitalists, colleges and politicians are working to make income sharing agreements the norm on campuses.

Consumer advocates are sounding the alarm.

Under these types of agreements, students forfeit a slice of their future income in exchange for money to pay for college. The contracts are often framed as a potential solution to the student debt crisis. Outstanding education debt in the U.S. is projected to swell to $2 trillion by 2022, eclipsing credit card and auto debt. The average college graduate leaves school $30,000 in the red today.

The model has attracted a flood of investors, including Google and Tony James, vice chairman of The Blackstone Group. Diane Auer Jones, principal deputy under secretary at the U.S. Education Department, recently said the government may offer income sharing agreements, too.

Here's how they work: Unlike a traditional loan, the recipient doesn't pay anything back until he or she secures a job following graduation. Then the borrower is on the hook for a certain percentage of his or her income for a set period of years. Since the agreements are a relatively new form of college financing, there isn't a lot of data available on how well they are working.

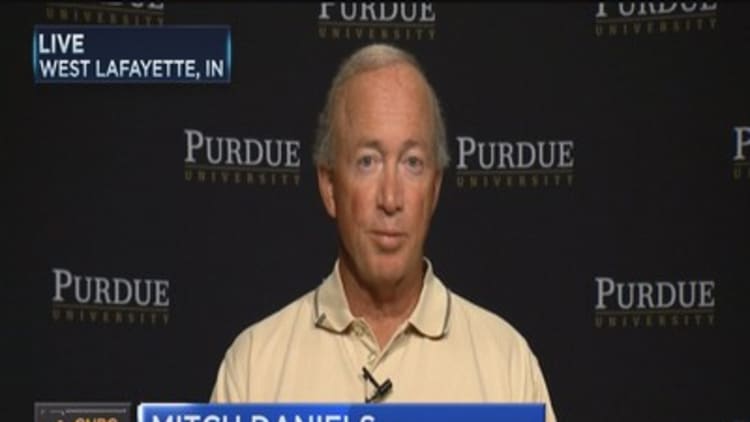

So far, only a small number of colleges provide them. Those include Purdue University, University of California, San Diego, Clarkson University, Messiah College and the University of Utah. "It's not a loan. It's not a grant. It's something new and different," according to Purdue's website. Clarkson University's website reads: "Students say goodbye to student loans."

However, consumer advocates are concerned that proponents of them argue the agreements aren't loans so they can operate outside of consumer regulations. "It's simply a disguised form of borrowing," said Ann Larson, co-founder of The Debt Collective, an activist group.

By making the case to Congress that these agreements are not loans, providers can essentially charge interest rates higher than many states allow, said Julie Margetta Morgan, a fellow at think tank the Roosevelt Institute.

"It indicates that the regulations that apply to loans, that are meant to protect consumers, are seen as an obstacle to forming ISAs that are exciting to industry," Margetta Morgan said.

And the fact that some of these agreements contain better terms for people who enroll in majors that lead to higher earnings could lead to discrimination, she said.

Indeed, under the University of Utah's income sharing agreement program, students in the top three women-dominated fields (elementary education, special education and nursing) would end up paying over $1,000 more to fund a $10,000 ISA than those in the three fields most dominated by men (electrical engineering, mechanical engineering and computer science), according to one recent analysis.

Proponents of ISAs say they hold schools accountable, since they're on the hook if their students don't make enough money to repay the funds. In addition, the agreements protect students by ensuring they don't have to make any payments should their income fall below a certain level, said Richard Price, a research associate at the Clayton Christensen Institute for Disruptive Innovation.

"We're all about a balance of protecting students but not handcuffing innovators," Price said.

Yet in most cases, an income sharing agreement will cost students more than federal loans, said Mark Kantrowitz, the publisher of SavingForCollege.com.

In a typical contract, a student who received $30,000 would go on to pay 12% of their income for 10 years, according to Kantrowitz.

Assuming that student began to make $50,000 a year — the average starting salary for a bachelor's degree recipient — and then saw a 2% raise each year, she would pay around $65,700 back in the end. "That's the equivalent of an interest rate of 18.4%," Kantrowitz said. (The rate on federal student loans is closer to 5%.)

A bill recently introduced in Congress would allow agreement providers to take up to 20% of a student's subsequent earnings.

"It takes a lot of gall to claim that charging more is the solution to the student loan problem," Kantrowitz said.

Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass., and other members of Congress recently wrote to the U.S. Education Department, expressing concern about the government's experiment with income sharing agreements. "It's vital to set aside the hype and look at ISAs for what they really are: a form of student debt," they wrote.

Beyond the repayment terms, the agreements contain other red flags for consumers, Margetta Morgan said.

In her review of many of the contracts, she found some included mandatory arbitration clauses, banned class action lawsuits and one forced students to use a particular bank. Students who fall behind on the payments can find they owe more than double the amount they were originally given.

"I'm very worried for students," Margetta Morgan said.

More from Personal Finance:

Dreaming of a US vacation home? 10 best places to invest

These cities gave the most money to charity in 2018

When unpaid debt can cut your Social Security payments