Sweden's new center-left government and its financial authorities are under huge pressure when they meet on Tuesday to tackle a mountain of household debt that is casting a long shadow over one of Europe's few economic bright spots.

Having slashed rates to zero to fight the risk of deflation, top Swedish officials are now in a quandary over how to rein in borrowing and house price rises without sending the real estate market into a downward spiral.

The country's AAA-rated economy is still one of Europe's strongest, with low public debt, sound state finances and banks among the best capitalized and most profitable in Europe.

Read More Sweden household debt poses 'contagion risk'

But consumers, barely touched by the financial crisis, have loaded up on cheap mortgages and caused Swedish property prices to triple over the last 20 years, prompting a warning from the IMF that the market is 20 percent overvalued.

Adding to the problem: Sweden has built too few houses for the last 20 years and its capital Stockholm is one of Europe's fastest growing cities.

Critics say the former center-right government added fuel to the fire by slashing real estate taxes and leaving 30 percent mortgage tax relief untouched.

Meanwhile, Sweden's household debt-to-income ratio has risen to above 170 percent - among Europe's highest.

The worry is that private consumption, nearly half of GDP, would suffer if rates rose or property prices fell.

"The longer we wait, the bigger the imbalances are," said Bengt Hansson, analyst at the Swedish National Board of Housing Planning and Building. "We already have a bubble, but we will avoid an even bigger bubble."

Consumers bullish

It will be hard to dissuade bullish Swedish consumers.

In Stockholm's frenzied housing market, buyers make multi-million crown offers to snap up flats they may only have seen in photographs. And cranes and scaffolding are common sights in suburbia as householders take advantage of generous tax breaks for home improvements.

Read More Why Sweden could become the new Switzerland

"We don't think it will crash badly," said Peter, a 47 year-old investment advisor, who with his wife Maria has just bought a house in Stockholm for around 12 million Swedish crowns ($1.62 million).

"It might stop going up for a while, but over the longer term we expect it to go up," he added, suggesting the lack of housing and population growth in Stockholm would support prices.

Attempts by regulators so far to slow credit growth - squeezing banks by making them put aside more capital and draw up voluntary mortgage pay-down plans - have not worked because interest rates have continued to fall.

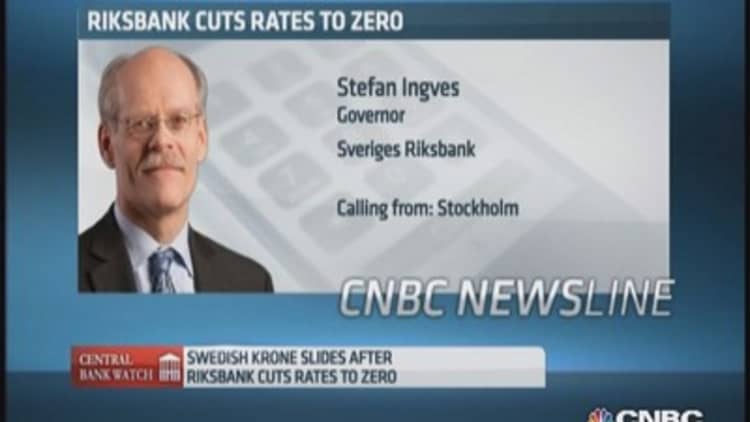

Last week the central bank cut rates to zero in an attempt to answer criticism that it is not doing enough to tackle another economic risk - deflation - even while it acknowledged the problem that would create in containing household debt.

"There is a fairly large consensus that household debt is a concern," Swedish central bank chairman Stefan Ingves said after the cut. "If households continue to borrow, we could end up with very big problems later on, and this is what we want to avoid."

What to do?

Sweden knows all too well the damage that a property bubble can do when it bursts: Deregulation in the 1980s led to a commercial property boom that bust in 1992 after which those properties lost nearly two-thirds of their value and Sweden had to nationalize two banks.

But since then borrowing has swelled again. By 2013, mortgages comprised 47 per cent of the Swedish banks' total lending from 30 percent in 2001. Another risk: those banks are largely financed with international market funding rather than deposits.

Many economists say the obvious action to take - lowering mortgage tax relief or reimposing real estate taxes - is politically difficult.

"We are not prepared to take measures that make it difficult for households to meet their housing costs or, in a worst case scenario, be forced to move out of their homes," Financial Markets Minister Per Bolund said.

Central bank governor Ingves favors tightening rules on mortgage repayments because currently only four in ten mortgage borrowers pay off their debt compared to nine in ten in the mid-1990s.

Lowering the borrowing ceiling of 85 percent of the value of a property is another option, but would hit first-time buyers.

The Swedish Bankers' Association has suggested voluntary rules to make Swedes pay down the first 50 percent of loans in order that "households pay off debts when interest rates are extremely low in order to be better prepared when...we have higher interest rates," Annika Falkengren, chairman of the association and CEO of Swedish bank SEB, said.

Sweden is close to becoming a cashless society: Report

But Sweden's competition authority has said this could limit competition and is yet to give its okay.

Looking at other countries' examples suggests that however Sweden's government, central bank and regulators decide to act, engineering a soft landing will be hard.

A drop in Danish and Dutch house prices for example triggered a fall in consumer confidence and spending, deepening the slump after the downturn of 2008-2009. And in the Netherlands, regulators made things worse by tightening mortgage rules as house prices were falling.

Sweden's neighbor Norway, where mortgage-linked debt stands at around 200 percent of disposable income, was forced to do a U-turn on tighter lending rules after house prices began falling late in 2013.

"We have to do enough, but not too much," Swedish central bank member Martin Floden said. "We cannot continue with this rapid rise in house prices and debt for ever, we need to in some way stabilize the development."