The audacious long-term budget path that House Republicans outlined on Tuesday is not going to become law anytime soon, if ever. Senate Democrats and President Obama will see to that.

Even so, the plan rolled out by the Republican majority in the House figures to shake up this year’s already contentious budget debate as well as next year’s presidential politics. By its mix of deep cuts in taxes and domestic spending, and its shrinkage of the American safety net, the plan sets the conservative parameter of the debate over the nation’s budget priorities further to the right than at any time since the modern federal government began taking shape nearly eight decades ago.

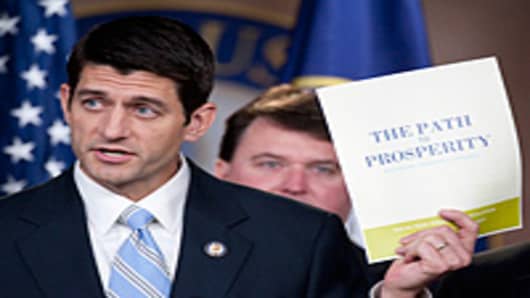

The ambitions of the first budget rolled out by the new House Budget Committee chairman, Representative Paul D. Ryan, a Wisconsin Republican, cannot be understated. It poses huge political risks for Republican candidates for Congress and for the White House in 2012. After Republicans successfully campaigned in last year’s midterm elections partly by criticizing Democrats for cutting Medicare as part of Mr. Obama’s health-care overhaul, they now propose to eventually privatize Medicare and turn Medicaid into a sharply limited block grant to states.

Because details remain sparse, the Congressional Budget Office could not estimate precisely the potential savings for Mr. Ryan’s plan, which the Republican-controlled House Budget Committee is expected to approve Wednesday. House Republicans say the budget would cut $5.8 trillion from projected spending in the 10 years through the 2021 fiscal year, and $6.2 trillion more than Mr. Obama’s budget would. But the Republican projections could not be independently confirmed. Longer term, the budget office said, the plan would allow the government to run a surplus by 2040.

The Republican plan also would slash individual and corporate income taxes by more than $4 trillion below current projections, somewhat offsetting the spending cuts and limiting the overall reduction in the deficit. Details on tax cuts and the closing of loopholes would ultimately be filled in by committees with jurisdiction over domestic programs and taxes.

Under the Ryan plan, military spending would not be cut any more than the $78 billion in cuts President Obama has proposed.

“Washington has not been telling you the truth,” Mr. Ryan said in a short video making the case for bold action. “If we don’t reform spending on government health and retirement programs, we have zero hope of getting our spending — and as a result our debt crisis — under control.”

His plan would go beyond the bold packages recommended in December by bipartisan majorities of two separate debt-reduction panels — Mr. Obama’s 2010 fiscal commission, which was headed by Erskine Bowles, a Democrat and former White House chief of staff, and former Senator Alan K. Simpson, Republican of Wyoming, and the commission headed by the former longtime Republican chairman of the Senate Budget Committee, Pete V. Domenici, and Alice Rivlin, former director of the Congressional and White House budget offices.

It also would go further in shrinking government and cutting taxes than the changes that Congressional Republicans proposed in the mid-1990s after they last took control of the House — a showdown that ended to the advantage of Democrats.

The House Republicans’ proposal poses challenges for Mr. Obama as well. Many Democratic strategists, including some inside the White House and the president’s re-election campaign, see mostly opportunity: Pleasantly surprised that Republicans have defined themselves so far to the right, they see a chance for Mr. Obama to stake out a middle ground.

But with Republicans describing their move as a bold leadership stroke, their boast has the potential to feed a budding narrative — that Mr. Obama has declined to lead in proposing the steps needed to rein in a federal debt that is growing unsustainably as the population ages and health care costs keep rising.

Mr. Obama, in an unexpected appearance before reporters Tuesday at the White House, said the Ryan plan ensured that Republicans and Democrats would have “very sharply contrasting visions in terms of where we should move the country.”

“I’m looking forward to having that conversation,” he added.

The White House later issued a harsher statement from the press secretary Jay Carney.

The Ryan plan, it said, “cuts taxes for millionaires and special interests while placing a greater burden on seniors who depend on Medicare or live in nursing homes, families struggling with a child who has serious disabilities, workers who have lost their health care coverage, and students and their families who rely on Pell grants.”

“The president believes there is a more balanced way to put America on a path to prosperity,” the statement said.

Administration officials gave no hint that Mr. Obama planned to spell out that balanced approach. The 10-year budget he outlined in February did not tackle the fast-growing entitlement costs — for Medicare, Medicaid and, to a far lesser extent, Social Security — that are driving long-term projections of the debt. While proposing major changes to Medicaid and Medicare, Mr. Ryan also declined to propose changes to Social Security, reflecting Republicans’ wariness of alienating older voters.

Deficit hawks in both parties praised Mr. Ryan for the breadth of the plan. But they criticized him for not proposing to cut military spending more or to raise tax revenues.

Like the Bowles-Simpson fiscal commission and other bipartisan groups, Mr. Ryan would eliminate many, though unspecified, income tax breaks to generate greater federal income. But unlike the other groups, he would use the new revenues only to lower tax rates to a maximum 25 percent for individuals and corporations, down from 35 percent. Again, details would be left to the appropriate legislative committees. The other deficit study groups would devote some revenues to reducing deficits.

“Because Ryan decided to basically ignore defense and not use any of the reduction in tax expenditures to reduce the deficit, it does place a disproportionately adverse effect on other parts of the budget,” Mr. Bowles said in an interview, including “the things that I think are important to protect the truly disadvantaged.”

Mr. Ryan was a member of the Bowles-Simpson panel but, like the other two House Republicans in the group, he opposed its recommendations for more than $4 trillion in 10-year savings for not going far enough in reducing health care spending.

His plan underscores just how much the influx of Republican newcomers to the House, many of them Tea Party adherents, have hardened conservatism there.

In the past two years, House Republicans distanced themselves from a similar plan that Mr. Ryan proposed. Even after the midterm elections in November, when he was in line to become budget committee chairman, Mr. Ryan said in an interview that he probably would have to moderate his proposals to win other Republicans’ backing.