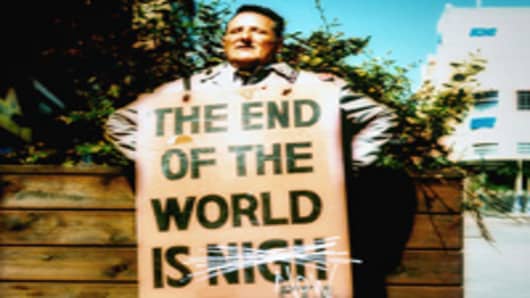

The resounding view on Wall Street and among many financial regulators and veteran lawmakers is that there will be a catastrophe if the United States does not raise its debt limit in the next few days.

But will the sky really fall?

It is a question more people were asking as the nation’s cash dwindled and lawmakers remained stuck in gridlock before the framework of a settlement emerged late Saturday. President Obama and Congressional leaders were working Sunday to hammer out an 11th-hour deal, and then must hope it can pass in both chambers of Congress this week.

Most people would rather not risk finding out and are hoping lawmakers can turn the framework into a bill that would raise the debt ceiling. But in recent days there has been growing attention on a few economists and financiers who have been arguing that it would be alright to miss the deadline — and even, a few of them say, default on payments to the nation’s bondholders.

These economists and traders argue that lawmakers need to focus on the nation’s long-term financial health rather than its current bind. They point to historical examples involving local and national governments that defaulted on some obligations and said the short-term pain that befell those places when they tried to borrow again eased over time.

In the case of the United States now, they say such short-term pain would be worth it if it helped lawmakers achieve a broad-sweeping plan to fund the country’s future – including costly programs like Social Security – without running such a large deficit. A few on the fringe even say the country would be better off if it wiped its hands of some or all of its debt because it might mean future generations of workers will not have to see taxes go up as much as they are otherwise likely to do.

“We have an opportunity now to get ahead of this and we might not in a few years,” said Christopher Whalen, who writes the Institutional Risk Analyst news letter. “If a democracy requires more time, then take more time. I don’t think a default is as big a deal as people say it is because where do investors go?”

Indeed, most investors believe they have few safer places to park cash other than the Treasuries that the United States issues to borrow money. Recently, as lawmakers failed day after day to reach a deal, investors have piled into long-term Treasuries, paying more to purchase them and driving down the United States’ borrowing cost. That may be because of weak economic data that has thrust the prospect of stocks into question, but it also underscores the unique status Treasuries hold as a global safe haven and a currency in countless financial transactions each day.

No one really knows what would happen if the United States defaulted on its debt, and a default could come in many forms, including a late payment of interest, a renegotiation of the absolute level of debt or missed payments of some of the government’s other obligations, like payments to its vendors. The idea of some sort of default has been tossed around by big names on Wall Street and Washington, including by Stanley Druckenmiller, a private investor who spent many years working with the billionaire George Soros. In May, former president Bill Clinton reportedly said at a panel that “it might not be calamitous” if the country defaulted on its debt for a few days.

It is difficult to separate viable proposals from political posturing in the budget debate, and the warnings given on both sides may be exaggerated. There are no historical examples that could be considered directly comparable. Several Republican lawmakers have been urging their peers to take more time on the debt talks, saying doomsday is not imminent. The Obama administration, which months ago announced Aug. 2 as the deadline, has vigorously disagreed. Historians still debate what would have happened in 2008 if there had not been a bailout for the banking system. Many in Washington and on Wall Street had argued there would have been a catastrophe back then if the government hadn’t intervened.

The question really is whether United States Treasuries, the country’s instrument of financial power, is something to be preserved at all costs, as most economists say, or if their status gives the country some leniency in the markets if lawmakers decided to temporarily default, for instance.

“It’s just too risky.”

Last week, a Pew Research Center survey found that just under one-quarter of Americans believe that lawmakers should not compromise to achieve a quick deal and should instead “stand by their principles, even if it means the government goes into default.” The percentage urging a default over a compromise was higher — 38 percent — among Republicans.

Still, calls in recent days to economists and financial historians turned up very few who said the country should experiment with default. That is “disaster talk,” said John Makin, an economist at the American Enterprise Institute. “It’s just too risky.”

Niall Ferguson, a historian at Harvard, said, “hey, wait a second, we should not be talking about the United States in the same breath as Argentina and Russia,” both of which defaulted on their sovereign debt around the turn of the century. He added, “The very fact that we’re doing this is bordering on the surreal.”

Tyler Cowen, an economist at George Mason University, said “come Sunday at 8 p.m. if it’s still a mess, bad things will happen. It will be another run on the shadow banking system like 2008.” The debt ceiling, he said, must be raised “any way possible at this point. To avoid catastrophe.”

To all this, Jeff Hummel, one of the economists advocating some of default, says “too late.”

Mr. Hummel, a professor at San Jose State University, has been predicting since 1993 that the United States will default on its debt. His view is driven by the unfunded liabilities the government has taken on for future benefits, and he says the nation will simply not be able to pay them or finance them all with debt.

He says it would be better to cut bait now.

“If I had my choice, I would repudiate the entire debt and use any available assets to pay Social Security,” he said.

While acknowledging that his views are "pretty extreme," Mr. Hummel said he thought it was more ethical to focus on providing money to Social Security recipients over the long run. That’s because they were forced to put money in, as opposed to parties that bought Treasuries, which are after all, an investment.

In the 1840s, he said, several states like Maryland and Louisiana defaulted and many of them passed state Constitutional procedures related to their debt, blocking them from getting into such debt levels since then. He acknowledges that a default would make it harder for the United States to borrow money, but he doesn’t think that’s a bad thing. "You can think of a default as a balanced budget amendment with real teeth," he said.

Besides, Mr. Hummel said that in the long run freeing the nation from debt would "increase the value of human capital," because people would not be taxed as much in the future to pay off the debt, so they’d be able to keep more of their earnings.

What’s impossible to know of course is how that potential gain would compare to all the economic damages that would come to the nation if the financial markets no longer wanted to lend to the United States.

And it’s hard to know how bad it would be right away. Many companies hold their savings in Treasuries and their businesses could grind to a halt if those bonds lost much value. Financial markets that use Treasuries to back trades could freeze. Also many people say the markets are more prone to panics now than in decades past and central banks do not have many more tools to use if we hit another panic so soon after the financial crisis.

Market pundits have already been changing their views on some types of defaults. Whereas many said for weeks that a downgrade of United States bonds by the ratings agencies would be bad, the market has started to accept that as likely and it is not clear that such an outcome would hurt Treasuries.

Standard & Poor’s has suggested that the lack of a meaningful plan to cut the deficit could lead it to a downgrade by mid-October. Moody’s on Friday said it would give the government even more time to work on a broader budget plan, but it warned that a missed payment on debt would result in a downgrade.

To some degree, even if the government stays current on its debt now, the debt may become worth less over the long run to the investors who hold it because many investors expect the dollar to weaken — which would lower the value of United States bonds to foreigners. In that sense, the country’s financial power may be already fading.

Mr. Druckenmiller, the investor, who did not comment for this article, told The Wall Street Journal in May that Treasury investors would have more confidence in their United States debt holdings if the nation worked out a big-picture solution to its deficit. If doing so takes so long that the country temporarily misses interest payments on its debt — a technical default — then so be it, he said.