Farming can be a tough business. The work is hard, the hours are long, and the profits unpredictable at best.

But Robert Warren had a secret weapon: crop insurance. It helped make the man who describes himself as “just a dumb farmer” into a multi-millionaire, with properties in North Carolina, South Carolina and Tennessee.

It turned out that Warren made his millions by abusing the taxpayer-backed federal crop insurance program for years, collecting more than $9 million in bogus claims.

He pleaded guilty to two conspiracy counts in 2005 after authorities found he had directed his workers to scatter ice cubes and mothballs in one of his tomato fields in Cocke County, Tenn., then sent in the pictures to show his plants were damaged by a “hailstorm.”

That claim alone netted Warren more than $80,000, according to court documents.

Warren’s wife, two employees, an insurance agent and a claims adjuster also pleaded guilty.

“The defendants’ involvement with the (crop insurance) program was conceived and born in fraud,” wrote Assistant United States Attorney Richard Lee Edwards in Warren’s 2005 sentencing memorandum. “(T)hese defendants simply sat around the kitchen table and created the production history figures which they submitted to the insurance company and the USDA.”

Despite stories like Robert Warren’s, Congress is set to implement a major expansion of the crop insurance program, which currently costs taxpayers around $7 billion a year.

As lawmakers try to complete a new five-year farm bill—the Senate approved its version on Thursday —there is widespread support on both sides of the aisle for replacing direct assistance to farmers with crop insurance. The change is aimed at saving roughly $2 billion a year over the current system.

But CNBC Investigations Inc. has found that none of the proposals to expand the program would add new measures to combat fraud, even though government auditors have repeatedly warned—even before the proposed expansion—that the Department of Agriculture is not doing enough to deal with crop insurance fraud, which costs taxpayers as much as hundreds of millions of dollars a year.

Lucrative Business

Crop insurance allows farmers to protect themselves from weather, disaster and market-related losses. The government subsidizes their premiums, and covers a portion of the claims paid by the 16 private insurance companies that participate in the program.

The companies wrote $114 billion in coverage last year. The government subsidy helps make crop insurance a lucrative business for the insurance providers, according to government data which shows a 23 percent rate of return.

Among the companies with crop insurance arms are Archer Daniels Midland, Deere and Wells Fargo.

Little wonder the industry lobbied heavily for a shift to crop insurance, spending $730,000 on the effort last year alone.

“Crop insurance has become the risk management tool of choice by farmers representing all commodities and politicians representing both sides of the aisle for one simple reason. It works,” said American Association of Crop Insurers spokesman David Graves in a statement.

But others say it is not working as well as it should.

“We have looked at USDA and what it’s doing to try to identify potential fraud, and found that it could be doing more,” said Lisa Shames, Director of Natural Resources and Environment for the Government Accountability Office, in an interview.

While the USDA analyzes claims data to search for signs of fraud, the GAO reported in March that the agency all too often does not follow up suspicious claims with field inspections, “increasing the likelihood that fraud, waste or abuse occurred without detection.”

It was the latest in a series of reports by the GAO on waste, fraud and abuse in the crop insurance program.

The most recent study found that in 2010, the agency failed to complete field inspections for 28 percent of the suspect claims. Nor did it give insurance companies some of the data they might be able to use to deny fraudulent claims.

But Shames said some of the agency’s shortcomings are even more basic.

“They’re also not taking advantage of less labor-intensive tools like sending out warning letters,” she said.

In its response to the GAO report, USDA cited “resource limitations”—declining budgets—for the issues, but said it was looking for ways to streamline the process.

“Everyone involved in the crop insurance program routinely looks for ways to improve oversight,” the agency said.

Fox and Hen House?

Other critics say the insurance companies have little incentive to monitor fraud on their own, since the government covers much of their losses. And in some cases, like Robert Warren’s, insurance agents and adjusters are complicit in the fraud. But David Graves of the crop insurance trade group defends the industry.

“The crop insurance industry has worked hard to ensure that the incidence of fraud is at a minimum and is far below other lines of property and casualty insurance,” his statement says.

Bertis Little, a professor of computer science at Tarleton State University in Texas and an expert on the crop insurance program, says crop insurance fraud rates are below those of property and casualty insurance, though he cautions that his research is ongoing.

“The figure is less than five percent and has demonstrated a consistent decline,” he says in an e-mail to CNBC. The Insurance Information Institute puts the rate of fraud in all other insurance at around ten percent.

Tarleton State University has a contract with the USDA to analyze claims data in the crop insurance program.

But Lisa Shames at the GAO is unconvinced.

“There is no readily available figure on the extent of fraud,” Shames said.

In California, Assistant United States Attorney Kyle Reardon agrees there is more fraud than meets the eye.

Last year, he successfully prosecuted Stockton farmer Gregory Torlai, convicted by a jury on 16 fraud counts.

“It was very brazen,” Reardon said.

In one instance, Torlai filed a claim on high desert scrub land in Susanville, California, that he claimed was a wheat field.

“The areas Mr. Torlai claimed to have irrigated and planted wheat crop many of them were rocky, and I’m not talking small rocks, we’re talking rocks that were dishwasher size or larger in some cases,” Reardon said.

Torlai, who was sentenced to two and a half years in prison, is appealing his conviction.

Reardon says he has little doubt there are more cases like Torlai’s to be prosecuted.

“The program is hundreds of millions of dollars large, we’re dealing with a lot of money here so my personal opinion is the Mr. Torlai is just the tip of the iceberg in a lot of ways,” he said.

Eye in the Sky

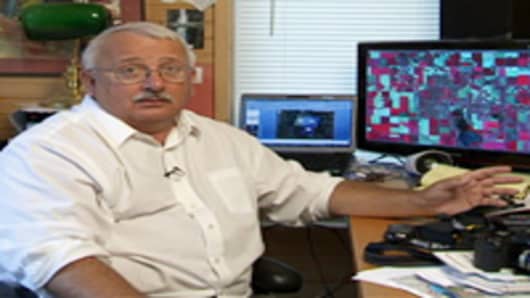

The proposed expansion of the crop insurance program means John Brown could have a lot more work on his hands.

Brown, a private contractor based in Missouri, is an expert in image analysis who has been investigating crop insurance claims for nearly 20 years, working with prosecutors and the USDA.

Using technology adapted from the medical field as well as a store-bought GPS, he analyzes satellite images to detect signs of fraud. Brown helped crack the case of Robert Warren, the farmer with the ice cubes in his tomato field.

He says he knew long before he visited the farm that something was amiss. In the satellite view, the color red represents not tomatoes but chlorophyll. The satellite images showed Warren had not planted nearly the amount of tomatoes he had claimed.

“All I saw was a sliver of red on the field and that was clear evidence that these people were pulling a scam.”

Brown says he is surprised the government is considering expanding crop insurance without adding more resources to fight fraud.

“Obviously if there’s more money available, there’s going to be more people out there that’s looking for loopholes and schemes to take advantage of that money,” he said. “It’s going to take more people in the field, more agents, more people in the risk management agency, more people on task force, more people with satellites.”

Now that the Senate passed its version, the House will begin working on its version next month. The current law, which governs all federal agriculture policy including nutrition assistance and food stamps, expires Sept. 30.

- By Scott Cohn | CNBC Senior Correspondent

- Additional reporting by Michael Tomaso