If Amazon is willing to lose money on tablets for the chance to make some on media and merchandise later, why not do the same in phones?

Let's take a step back to look at the numbers. On the face of it, selling anything at a loss sounds like a very bad idea. After all, the more "successful" the product is, the more money you lose, right?

Well, in some cases it's actually more complicated than that.

Take wireless carriers. They're already in the business of selling smartphones at a major loss. That iPhone you paid $200 for? The carrier paid Apple closer to $650 for it in the first place.

The reason the carrier can do this is because it has a nearly ironclad method for getting its money back: At the same time it sells you the phone, it ropes you into a two-year wireless contract with a hefty data plan. As a result, the carrier ends up making money after a year or so, even though it initially takes it in the shorts.

Or take search. In a real sense, the whole business is about spending money to make money.

Consider: Google spends billions of dollars on data centers and engineering brains, only to give the search product away for free. Not only that, they spend even more — $100 million in 2010 on the Firefox browser alone — to get more people to use its free product.

The payoff? Advertisers want to reach Google's search audience. So even though Google doesn't lock search users into two-year contracts in exchange for a subsidized service, it still has a pretty-much ironclad way to get its money back.

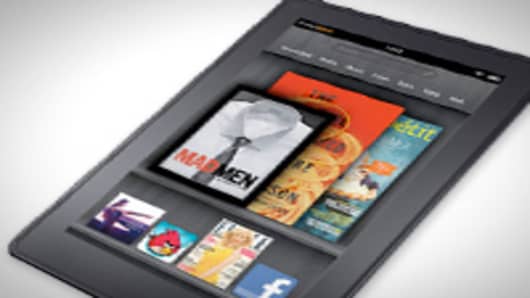

It's probably fair to think of these latest loss-leader hardware efforts in the same context. Amazon knows that Kindle Fire users are more likely to buy ebooks, movies and eventually other goods once they have the hardware in hand. New data-crunching capabilities allow Amazon higher confidence on a day-to-day basis about how its bet is playing out.

Yes, the phone market is trickier. Phones are more personal objects than tablets, in part because they're often attached to a long-held number. To get consumers to buy a phone en masse, Amazon would have to do more than convince them that its phone is cheap and decent; it'll have to be better than the phones most already have.

And then there's the matter of eventually making money.

Jason Goldberg, CEO of high-flying retailer Fab, told me this week that tablet shoppers convert to purchase at twice the rate of smartphone shoppers.

Can Amazon build software into the phone that's good enough to change that? In other words, can Amazon build a phone that's the ultimate shopping companion? As in, you take the phone with you to the store, scan bar codes, and buy everything on Amazon instead?

If so, a phone could make sense — especially if Amazon works out a scheme where it ends up directly collecting customers' monthly bills. (If Amazon's already billing you every month, how easy would it be to tack on Prime membership, or include other easy upsells?)

But there a couple of unique dangers in hardware: One, if the product flops, inventory costs can be crippling.

Two, the hardware can actually be too popular — for instance, if a customer likes a money-losing product enough to buy one for every family member, it will take that much longer for Amazon to recover its costs.

Bottom line: If everything goes right, an Amazon phone could make a lot of sense. But a lot could go wrong.

email: tech@cnbc.com