Reid Hoffman:The billionaire philosopher

As a child, Reid Hoffman would fixate on certain things. “I went through a period where I was playing a lot of board games … I decided I was interested in fantasy role-playing games. Not only, of course, would I play them with my friends but I got involved in publishing some of the game reviews and supplements,” he told CNBC’s “The Brave Ones.”

Aged 12, he worked as an editor for Chaosium, which published the fantasy game RuneQuest, editing supplements for its creator Steve Perrin.

Games helped Hoffman get known for his business strategies. “You learn how to identify how a set of tactics come together in a strategy and which set of tactics you combine, which play into this circumstance that when you're playing against other players, you have to think about what their tactics and what their strategy (are), and how your strategy plays against theirs.”

Random outcomes based on the roll of a dice also influenced him. “You actually have to have a flexible and adaptive strategy because not everything is controllable.”

Another fascination was where he should study, and Hoffman was keen on the Putney School in Vermont, where students mix academic classes with working jobs such as oven stoker and looking after the school’s sheep.

“It was, drive oxen through the woods, and you know, kind of do blacksmithing and woodworking and all these things I’d never had experience with before.” He applied and got in without his parents knowing but had to push them to let him go, given the school was so far from the family home in Berkeley, California.

“With both my parents being lawyers … from a very early age whenever I wanted something, I’d have to make a case.” They let him go based on the school’s mix of academic studies and work experience.

But putting a bunch of young people in a semi-supervised place was challenging, Hoffman said. “Boarding schools are a lot like ‘Lord of the Flies’ … I learned a lot about how do I think about human nature, conflict between people … The first year of boarding school was probably one of the hardest years of my life, but also I think, it was one of my most instructive.”

Hoffman’s interest in philosophy grew over time. “I didn't realize it was actually philosophy, it was always a question of who are we and who should we become and what is the meaning of life. And I didn't really realize that those were philosophical questions until, maybe, I got to college,” he said. In 1985, he initially decided to study structured liberal education at Stanford University, a course covering philosophy, literature, art and history, but then realized a new major called symbolic systems would better suit him.

Hoffman met Stefan Heck on the symbolic systems course at Stanford, before the two worked at Apple in the 1990s. “(It) combined philosophy, programming, logic, computer science, psychology into one new major … It was the reinvention of AI (artificial intelligence) if you like,” Heck told “The Brave Ones.”

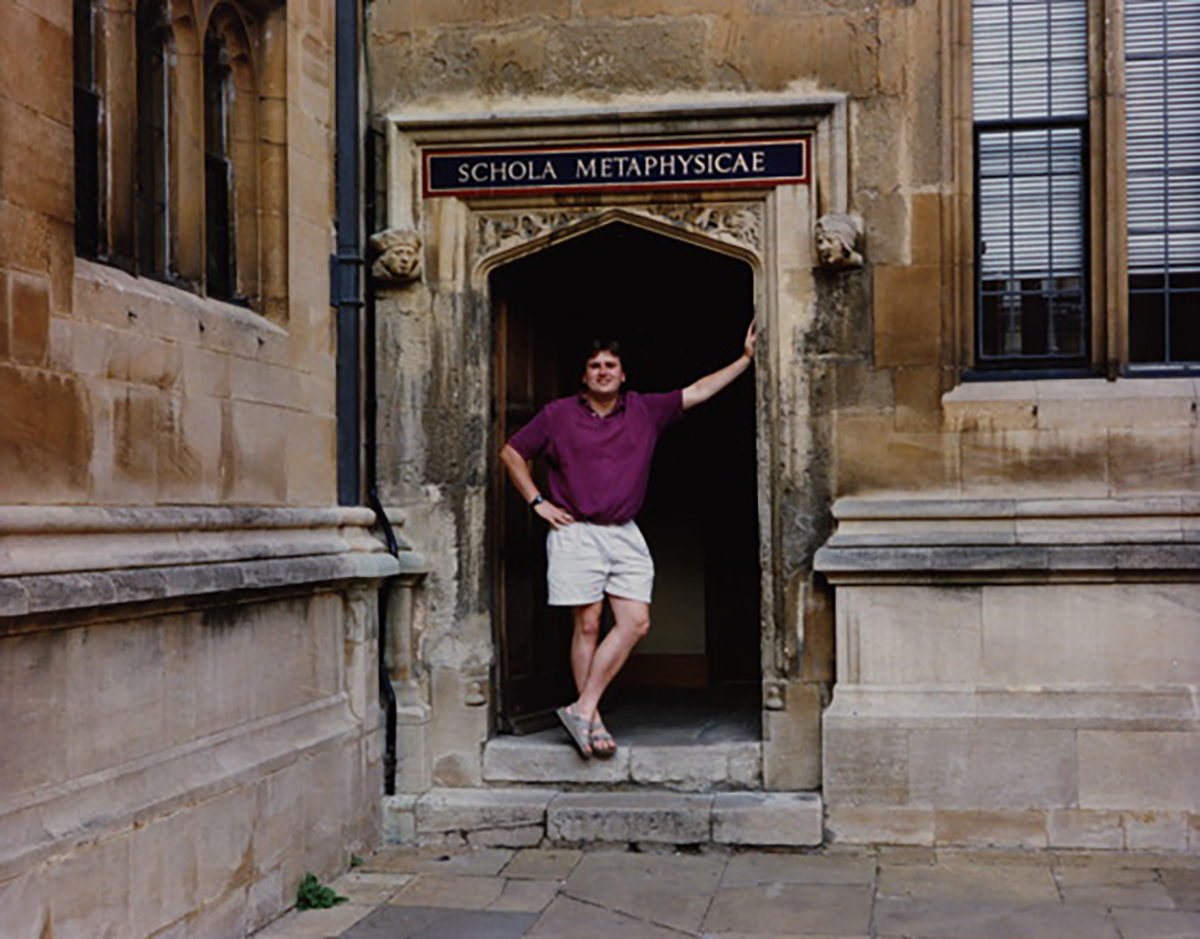

Then Hoffman went to Oxford University for a master’s degree in philosophy. “The thing I really wanted to dedicate myself to was how do we improve ourselves as individuals and society, and I originally thought I'd become an academic,” he said. But after a few months he realized academia wasn’t for him. “Scholarship was excellent, but you write books that 50 people might understand … but what I was much more curious about is how do we all, like, evolve together? How do we all learn from each other?”

Software was the answer. “It was thinking back to my time at Stanford where I was, like, ‘Oh, wait, software is this new medium by which we interact with each other, by which we kind of parse the universe.’ There's this German term called ‘weltanschauung,’ world view. Software helps shape that for us. I could go work in that.”

He called Heck, who suggested he apply to Apple. After working there on eWorld, essentially an early social network, he left to see if he could create a product that would make “a huge difference” to people. SocialNet, launched in 1997, was the result, “(It was) a dating service, it was a professional networking service, it was roommates, it was sports partners like golf or tennis, and how do you find the right people?”

It was an intense time. “One of the things I learned from starting SocialNet was that starting a company is jumping off a cliff and assembling the airplane on the way down. And what you're realizing after you've jumped off this cliff, after you've said, ‘Hey, we're going to go start this new thing,’ is, ‘Oh, I don't have a lot of the parts. I need new people to help me with this. And I don't know what order to assemble this plane in.’”

He had to learn how to finance the business, hire people, create a launch strategy and find customers. He had to constantly check whether it would work. “And you want to (be getting) as fast as possible to that information because you want to know as fast as possible, ‘Do I need to pivot to something else?’ Because the expression of ‘fail fast’ is not seeking failure, it's adjusting to succeed sooner.”

He advocates getting a minimum viable product out to the market as quickly as possible to get feedback. “If you’re not embarrassed by your first product release, you’ve released too late.”

But SocialNet ended up failing in part because it didn't use the internet to find new users, Hoffman said. "We thought, 'Oh, we'll have partnerships with newspapers and magazines,' and none of that worked."

While running SocialNet, Hoffman got a call from Peter Thiel, a friend from Stanford, to say that he and computer science graduate Max Levchin were starting a company and wanted his input. “And they said, ‘We had this great idea, it's encryption on mobile phones.’ And I say, ‘Well, that's a terrible idea, but you're a very good friend of mine, so I'll come help you with this.’ And so I join the board. This is the company that later became known as PayPal.”

As the company grew, they needed a chief operating officer, so Hoffman stepped off the board. “I very quickly became Thiel's ‘firefighter in chief,’ which was: ‘I want you to solve this problem, I want you to solve this problem, I want you to solve this problem. Make sure eBay doesn't drive us off of service. Make sure Visa doesn't shut us down. Persuade the federal government that it's okay that we're not a bank.’”

“There was a whole set of fires at PayPal where if you didn't solve them, (the) value of the company is zero, out of business.”.

PayPal’s initial idea was to provide payments via PalmPilot, an early mobile device, but the company found that people were using it to pay for items on eBay. “For the first week, everyone's like, ‘Oh who are these people? We should get them off our service. They're not our customers.’”

“I was like, ‘Wait a minute. These are the people using our product. These are our exact customers.’ And we pivoted entirely away from focusing on PalmPilots to email payments through eBay using PayPal.”

Hoffman describes his time at PayPal as the inflection point in his career. “That was the thing that made me learn all these key lessons about how you do consumer internet companies … not only (how) you learn how not to fail, but how do you learn to succeed. And the network, the so-called PayPal mafia, which I refer to as the PayPal network, was instrumental in figuring out what the next phase of web 2.0 was,” he said.

PayPal’s alumni include Elon Musk, founder of X.com, which bought the company that became PayPal in 1999, Steve Chen, one of YouTube’s founders and Yishan Wong, who went on to be CEO of Reddit.

After PayPal was sold to eBay in a $1.5 billion deal in 2002, Hoffman planned to take a year off. “I looked around and I realized Silicon Valley had gone crazy, that everyone had thought the consumer internet was over,” he said.

“It was like, ‘OK, the consumer internet's done. We're moving on. We're doing clean tech. We're doing enterprise software … And I went, ‘They're wrong. Oh, I can't take a year off. I'll take six weeks off and then I'll come back and I'll start the company that I'd been thinking about, LinkedIn, and I'll invest in a bunch of other interesting companies.’”

John Lilly, who works with Hoffman in his current role as an investor at Greylock Partners, told “The Brave Ones” that LinkedIn is “a bit like putting (Hoffman’s) brain online and enabling everybody to work that way.”

“His sense was, you know, ‘We have these resumes, we have these connections that are hard to see. If I can go use the web and connect people virtually, that unlocks a power and kind of makes real these things that are in everybody's heads right now.”

Hoffman’s contacts initially doubted his idea for an online professional network. “And when I first started telling a bunch of my network about this idea, I basically got the: ‘Oh that will never work.’”

“I remember thinking I had this high-quality network, why would I make it available to everybody else?” Lilly said. “And (Hoffman’s) like: ‘Well, could you just do it?’ And I said, ‘Fine, I'll sign up to LinkedIn.’ I was like, you know, five, maybe number seven, or nine, or 12 or something, on the service.”

Nancy Lublin, the founder and CEO of text-message support service Crisis Text Line, was also unsure about LinkedIn. “I remember thinking it’s kind of messy but it's a really good (idea) … but I still think it’s messy and I still think it's a good idea,” she told “The Brave Ones.” “When your design is ‘meh’ and you’re still slaying (doing well), you’re onto something.”

LinkedIn took a while to get going, Hoffman said. “Sometimes these consumer internet ideas just take off. Sometimes they take a year or two. LinkedIn was one of the ones that took a year or two in order to work … But I literally would have people assert to me, ‘I'll never use LinkedIn. This is never the thing for me.’ And then, of course, a year or two later that was their primary site that they were using.” Once people built up their connections on the site, it helped them solve business problems such as finding someone to sell to or hire.

“Eventually, you would get to a network that all of sudden could transform your economic path, your economic opportunities. And that would be a surprise and delight moment for people,” Hoffman said.

In the spirit of helping entrepreneurs, in 2013 Hoffman published LinkedIn’s pitch deck to Greylock Partners for its series B funding. The pitch took place in August 2004 when Friendster and MySpace were the rising social networks at the time, and hardly anyone had heard of Facebook, Hoffman summarized in a blog post. Investors were also nervous because of the dotcom bust and LinkedIn knew it would need to address the fact that the business was not yet making money.

And it certainly wasn’t an obvious investment for Greylock, partner David Sze has said. “The best early-stage venture capital investments appear obvious in retrospect … such was the case with LinkedIn,” he wrote in a March 2014 blog post. But Hoffman and his team impressed with their attitude, which was “Bright, talented, aggressive/competitive, analytical committed to excellence, hard-working, intellectually honest, and risk-taking,” Sze added.

The fact that the network already had 900,000 members convinced Sze that building scale was “almost fully behind them already,” although that has since grown to more than 550 million users.

Greylock led a funding round that raised $10 million in 2004, and Sze said LinkedIn was hitting a tipping point, in a press release at the time. “It is poised to transform a number of large existing markets. In the United States alone, businesses spend over $8 billion per year to recruit talent,” he said.

In 2008, Hoffman hired Jeff Weiner as LinkedIn’s CEO, noting that the two had the same mission for the business: “What is the best way that we can help the most people in the world, transform and amplify their economic potential, connecting talent with opportunity?” Hoffman said. In 2011, the company went public, and after its first day of trading it was worth nearly $9 billion, against LinkedIn’s proposal of $3 billion.

Microsoft, which bought LinkedIn in 2016 for $26.2 billion, had similar ideas, Hoffman said. “We ended up combining with Microsoft because Microsoft had this, ‘How do we make all the world's organizations productive?’. And we had a ‘How do you transform individuals’ career paths and how do you make individuals productive?’ And so that combination is, like, the friendship between the missions.” It's also a sale that could have earned Hoffman up to $2.8 billion, based on his share ownership of around 11 percent at the time.

One of Hoffman’s early investments was Facebook, in which he put an estimated $40,000 during an early funding round, around the same time that he started LinkedIn.

“As part of my days at LinkedIn, one of the people I'd helped was this entrepreneur named Sean Parker. And Sean calls me and he says, ‘Oh, there's this really awesome start-up that you really need to invest in called Facebook,’” he said. Parker, who went on to become Facebook’s president between 2004 and 2006, organized a meeting at Thiel’s office.

Thiel would lead the funding round and avoid any suggestion of conflict between the two social networks. “And I never thought there ever was a conflict, but appearances matter, too. And so we met them at Peter Thiel's office in San Francisco and that was, kind of, one of those investment decisions where you went, ‘Oh yes … We should definitely do this,’” Hoffman said.

“What was clear was that Facebook had an awesome product-market fit. That when they turned on (the website at) a college campus, within six weeks 80 percent of the students in the campus were using it more than six times a day.”

Hoffman also invested in photo-sharing site Flickr, audio site Last.fm and social gaming company Zynga among others and in 2009 became a partner at venture capital firm Greylock, after being approached by Sze, who had led the company’s $10 million LinkedIn investment.

Hoffman’s first investment was Airbnb. “I knew within two minutes of their pitch, this is one of the things I want to invest in because it was transforming the way that, kind of, travel worked … And when they kind of pitched me on, it's eBay but for space, I stopped them two minutes in and said, ‘No. I’m going to make an offer to invest. And, now, let's just have this be a working session’.”

But Sze wasn’t convinced. “(He) looked at me as I had brought them in and said, ‘Well, every VC (venture capitalist) needs a deal to fail on. Airbnb can be yours.’.” Greylock and Sequoia Capital ended up investing $7.2 million and Airbnb made more than $1 billion in revenue in the third quarter of 2018 and may go public in 2019. Hoffman says he loves his current investments, such as Nauto, a tech company founded by former classmate Heck that stops drivers getting distracted, and freight-booking app Convoy that aims to match shippers with truck carriers. “There's a whole stack of these things that I just go, oh my gosh, I can see how this is going to completely change the world,” he said.

But there were investments he passed on too. “I missed (payment app) Stripe with John and Patrick Collison. I missed (payment service) Square with Jack Dorsey. I missed Twitter with … Jack Dorsey. So the list of (companies) I missed … is equally long.”

He’s also provided seed capital to non-profits including Crisis Text Line. Founded by Lublin, former chief executive of volunteer-matching service DoSomething.org, Hoffman was interested in the organization because Lublin wanted to use tech to have an impact on people’s lives at scale.

“When Nancy presented the concept to me, I provided the seed capital to help launch Crisis Text Line as a standalone non-profit because it shared so many similarities with classic Silicon Valley start-ups,” Hoffman wrote in a November 2015 blog post. “It had a strong entrepreneurial founder with a track record of leading high-impact organizations … It had a clear product/market fit, and a scalable tech solution. To date, (it) has spent no money on marketing. Users find it through word-of-mouth.”

- “You actually, generally speaking, want to invent something that most people, the first time they think about it or hear about it … they think you're a little crazy, they don't think there's really a place for it, and then at year three, it's like, ‘Oh, yeah, that's obvious. Everyone always knew that was a really important thing to have.’”

- “Hire generalists, not specialists … You want generalist engineers, you want generalist marketers, you want generalist business development people. Because you're learning about what it is your product will do, what it is it will take (to) get your product or service to scale.”

- “Realize you're going to be learning and changing constantly. (It’s) … not any one particular technique as much as learning what's going on, getting a network of resources and people around you to help … and then constantly checking, ‘Am I on path? Is it working?’ Is this theory about how we're going to launch this product or how people are going to love this product … is that working or not? And you … want to know as fast as possible.”

In around two years, the organization had triggered nearly 2000 “active rescues” where police or medical staff were sent to stop an imminent suicide, Hoffman wrote. For her part, Lublin said Hoffman is unusual as a tech investor. “Reid has a very strong sense of social justice which I think also sets him apart from people in Silicon Valley,” she told “The Brave Ones.”

Lublin is also familiar with Hoffman’s lists, the notes he makes before meeting anyone. “I’ll get together with him and he'll be like: ‘Okay, I have these eight things I want to talk to you about’ and it looks to me like it's a list that he's been holding onto for like six weeks.”

Hoffman wants to make sure he gets the most out of meetings, he told “The Brave Ones.” “I actually put a little bit of thought into, oh, this would be good to talk about … And I have a list of that. It doesn't mean we have to do the list. But it means that as opposed to saying: ‘So how's the weather?’ … We can go to really interesting topics as soon and as quickly as possible.”

Hoffman is also known for his desire for scale, his friend from Oxford University and now McKinsey partner James Manyika told “The Brave Ones.” “Even as an investor and even as a CEO, as a founder, he's always thinking about things in very large scale. How big is this going to be? How much of the world will this touch? How much will it change things?” he said. In 2017, Hoffman started a podcast dedicated to the subject, “Masters of Scale,” which he calls “a hobby, really … a philanthropic activity.” He also published his third book, “Blitzscaling: The Lightning-Fast Path to Building Massively Valuable Companies” in October 2018.

Recent podcast guests have included Brit Morin, a former Apple and Google staffer who started online publication Brit + Co using crowdsourced content and now claims to reach more than 175 million users a month. Other interviewees include TaskRabbit founder Stacy Brown-Philpot, Spanx founder Sara Blakely and former Starbucks chair and CEO Howard Schultz.

Investing in AI technologies is also a big focus, Manyika said. “(Hoffman) is involved in a lot of efforts where AI is being used to tackle a lot of pressing, societal issues, whether it's solving things in health care, discovering new materials, or even, curing cancer, oncology.” Hoffman has invested in non-profit research company OpenAI, which focuses on the positive human impact AI can have, and has put $1.5 billion of his fortune into “impact investments” (that do good), according to Forbes.

Through all of his work, he wants to make the world better. “What I hope for and what I work for is a society and set of networks by which we make each other better. We learn how to improve ourselves and each other through connection, through dialogue, through collaboration, through working together. And the set of technologies, services that I want to build are those things that allow us to become our better selves as we help each other do so.”

The full episode of “The Brave Ones” featuring Reid Hoffman, is available on CNBC International’s YouTube channel

Design and code: Bryn Bache

Editor: Matt Clinch

Executive Producer, The Brave Ones: Betsy Alexander

Producer, The Brave Ones: Mary Hanan

Images: CNBC, Getty Images, LinkedIn and Reid Hoffman