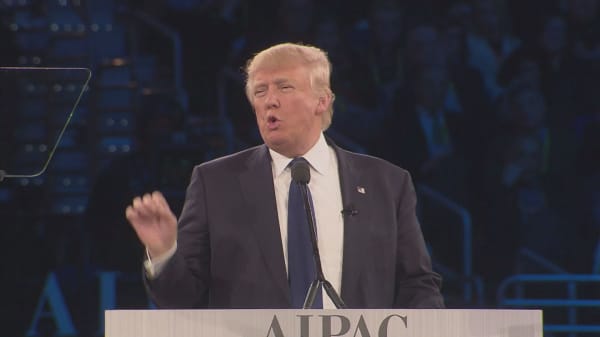

The centerpiece of Donald Trump's immigration policy — construction of a huge wall along the southern U.S. border — has been hugely popular with his supporters.

But how does he plan to pay the estimated multi-billion-dollar cost to complete it?

When he initially proposed the idea, Trump insisted he would simply send the bill to the Mexican government.

"We're gonna get the wall built," Trump has told reporters. "And Mexico's gonna pay for the wall … And they're gonna be happy about it."

Mexican officials have dismissed that idea

"We are not going to pay any single cent for such a stupid wall," former Mexican president Felipe Calderón told reporters at business conference in February.

So Trump has come up with another plan, by seizing a piece of the $25 billion in remittances that flow to Mexico every year.

"Mexico must pay for the wall," according to the billionaire Republican candidate's website. "We will not be taken advantage of anymore."

In addition to seizing money transferred back home by Mexicans living in the U.S., Trump has proposed tapping other sources of revenue. (Those include raising fees on everything from visas issued to Mexican CEOs and diplomats to shipments of goods coming into the U.S. from Mexico.