For entrepreneurs planning to build a start-up the right way, no one has left a clearer trail of how-tos than Alphabet's founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin.

Once graduate students at Stanford University working on the Google search engine, they now run an internet conglomerate worth close to $600 billion. They learned to modify and expand upon their big idea, get needed management help without giving up control, and manage risk and reward on the road to becoming a more or less mature enterprise.

They aren't perfect. The recent advertiser uproar over Alphabet's inability to identify offensive content on YouTube shows that even the Google founders are still learning. And the company also faces recent claims from the Department of Labor that a gender pay gap exists among its employees. But billionaires Page and Brin have shown a generation of wannabes in Silicon Valley and elsewhere how to do it right — and why their company fields millions of résumés annually.

Here are some of the key lessons from the Google founders' early days.

1. Start with a big enough idea — doesn't matter if similar ideas are out there.

There were already a number of web search engines before Page and Brin got together in 1995 — they just weren't very good. The Google founders had two big ideas. One was to base web search on the citation-ranking system academics used to rate the quality of articles in academic journals, a notion that was natural to the two professors' sons. The other was that search results should be based on a relatively "pure" ranking system untainted by their business need to generate revenue. They believed that a purer ranking system would be more useful and that consumers would trust it and use it more.

"We believe a well-functioning society should have abundant, free and unbiased access to high-quality information," Brin and Page said in a 2004 letter to prospective shareholders.

2. Be willing to compromise when you have to, including on your loftiest goals.

Google's founders referred to free, high-quality information as part of the company's "responsibility to the world" but by 2000 it was clear that the pure ratings weren't going to generate enough revenue to make Google a big, profitable company. So the task became to find ways to generate advertising revenue without compromising the search results.

That led, ultimately, to the paid listings that run alongside Google search results, an idea that revolutionized marketing because they were both highly relevant and priced by the click. That gave Google the running room needed to keep its primary search results free of so-called "paid inclusion" ads that users eventually rejected. The decision also led to litigation, later settled, claiming that Google stole the idea for auction-based pay-per-click advertising from GoTo.com, a start-up later purchased by Google's one-time arch rival Yahoo.

More from Upstart 100:

Reviving the American dream in Puerto Rico through entrepreneurship

4 tax reforms that can reinvigorate Main Street — and boost the economy

4 Chinese-backed electric-car start-ups planning a run at Tesla

3. Be willing to accept help from "adults" when you need it.

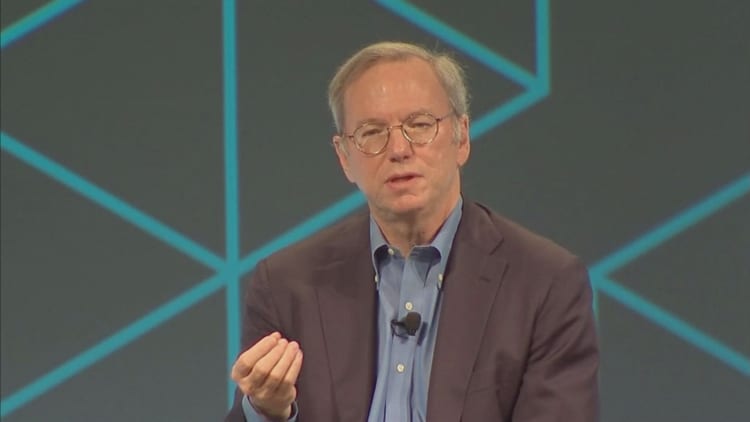

Recent headlines about Uber co-founder and CEO Travis Kalanick make this lesson abundantly clear. In 2001, Brin and Page hired Eric Schmidt to "provide adult supervision, basically," as Brin put it in a PBS interview with Charlie Rose. As the structure had evolved by the time Google went public in 2004, the trio ran the company together, with most vice presidents reporting to Schmidt, while Page focused on product development and engineering, and Brin zeroed in on deals and engineering. The former CTO of Sun Microsystems helped the young entrepreneurs, then eventually gave way to Page as CEO in 2011.

4. Culture counts but means more than free food and massages.

Another one for the new era of Travis: Google's top HR executive is also its chief culture officer, the person in charge of assuring Google lives up to the "Don't be evil" credo that dates to its early days. Former executives praise Google for everything from being progressive (by Silicon Valley standards) at identifying and promoting female executives, to an ongoing series of lectures and programs at the Googleplex headquarters and, of course, the infamous massages and free food. Put the culture together with nearly infinite resources, and it's little wonder the company fields a reported 2.5 million resumes annually.

5. Speculative, even strange bets, may be the business of tomorrow

When Google went public in 2004, Brin and Page said it wouldn't be conventional and would be willing to sacrifice short-term results for growth. Sometimes, that has taken the form of deals that were criticized at the time, like the 2006 purchase of YouTube, which took years to justify its $1.6 billion purchase price but now generates an estimated $10 billion-plus billion in yearly revenue and is the heart of Google's newly-announced TV service. Sometimes it takes the form of moonshot in-house projects that are still years away from profitability. Sometimes a product may not reach initial expectations, and is even considered a flop, but does find a valuable niche: Google Glass is now popular in the medical and industrial fields.

While the speculative bets have periodically hurt Google's stock price — Wall Street runs hot and cold on risk depending on how the rest of the business is doing — the approach is consistent with Brin and Page's promise to build their company for long-term wealth creation. In the 2004 IPO filing, they wrote: "In our opinion, outside pressures too often tempt companies to sacrifice long-term opportunities to meet quarterly market expectations. In Warren Buffett's words, We won't 'smooth' quarterly or annual results: If earnings figures are lumpy when they reach headquarters, they will be lumpy when they reach you. … If opportunities arise that might cause us to sacrifice short term results but are in the best long term interest of our shareholders, we will take those opportunities."

6. Consistency is the key, but is not the same as stubbornness.

The company's 2016 annual report noted reminded investors that the founders promised to make "'smaller bets in areas that might seem very speculative or even strange when compared to our current businesses.' From the start, the company has always strived to do more."

But a few years ago Google hired a Wall Street CFO, Ruth Porat, and made the decision to isolate the moonshot projects — from Google Fiber to Nest, self-driving cars and biotech start-ups — into an "Other Bets" segment which would clearly show how much they cost versus how much Google's core search business made. Other Bets lost $3.6 billion last year, but Alphabet as a whole had net income of $19.5 billion. Smaller companies that can't lose $3.6 billion may not be able to bet 4 percent of revenue, as Alphabet does, on longer-run ideas.

The company also, of course, changed its publicly traded name to Alphabet, which had over $90 billion revenue last year. In Google's 2004 IPO filing, it listed annual revenue of $962 million and a net profit of $106 million. The key to the whole approach is consistency, according to a leading analyst. "Google was growing approx. 20 percent on a $26 billion revenue run rate biz at the beginning of 2010 and is now growing 20 percent on a $104 billion run rate biz. Very rare," RBC Capital Markets analyst Mark Mahaney says. "Profit margins are intrinsically high and free cash flow is very strong. [Alphabet] is one of the strongest, most consistent fundamental stories in Tech. Period."

— By Tim Mullaney, special to CNBC.com