Those deductions include some of the most popular provisions of the tax code, because they allow households to cut their tax bills by writing off expenses like taxes paid to state and local governments.

But the proposal was short on details of just how the plan would make up for the shortfall created by lower rates.

Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin Wednesday repeated the administration's pledge that the proposal "will pay for itself" over time as the economy grows and the tax base widens. The theory is that, as lower taxes spur growth in the economy, the tax base will grow fast enough to make up for the shortfall from lowering tax rates.

It's an idea that's been around since the Reagan administration cut taxes in 1981. But there's little evidence that future growth makes up for the revenues lost when tax rates go down.

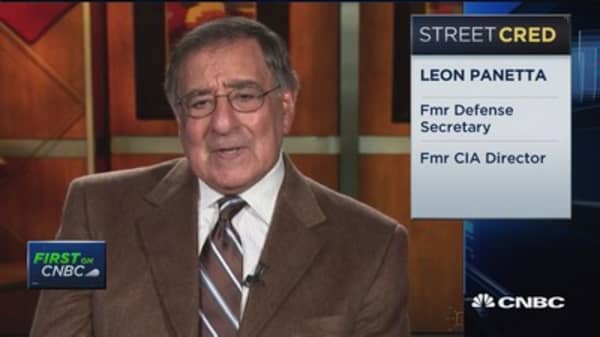

"This idea that growth can pay for these kinds of huge tax cuts is operating in fairyland," former Clinton administration budget director Leon Panetta told MSNBC on Wednesday. "That just doesn't work, so if you're going to do a tax cut, then show how you're paying for it."

With Congress already struggling to head off looming budget deficits, that assumption may be a tough sell, according to Jim O'Sullivan, chief U.S. economist at High Frequency Economics.

"While the administration can show tax cuts largely "paying for themselves" by simply changing economic assumptions, Congressional legislation is subject to stricter rules," he wrote in a recent note to clients.

So how will this plan affect my taxes?

No one knows. The plan is short on details, and Congress has yet to weigh in on where and how deeply taxes would be cut.

Trump has also promised to reduce taxes for the middle class, but the administration hasn't said how it plans to offset those cuts by eliminating specific deductions and other tax breaks. Without closing loopholes, the government would collect less money, federal budget deficits would get bigger and the national debt would continue to rise.

Trump administration officials insist that cutting taxes on individuals and businesses will spur growth, boost profits, create more jobs and wages — all of which gives the government more money to tax.

It sounds like a great idea. Will it work?

That's a multitrillion-dollar question. Mnuchin has conceded that, if you don't factor in faster economic growth – a process known as "dynamic scoring" – the math may not work.

The problem is that the strategy has been tried twice – most recently by President George W. Bush and earlier during the Reagan administration. In both cases, tax cuts were based on the premise that faster economic growth, along with higher profits and wages, would make up revenues lost from lower tax rates.

It didn't work, and budget deficits added trillions to the national debt.

On the other hand, after tax rates went up during the Clinton administration, federal tax receipts also went up and the national debt as a share of GDP went down.