Michael Cohen, President Donald Trump's personal lawyer, was paid $600,000 by AT&T last year to help the company understand how the new administration might approach its proposed merger with Time Warner, the tax reform debate and other issues, according to internal documents.

The Swiss pharmaceutical giant Novartis, meanwhile, said it paid Cohen $1.2 million to help the company navigate the Trump administration's proposed changes to the Affordable Care Act. And a Korean aerospace company pursuing a major defense contract confirmed that it had paid Cohen $150,000 in November for what the company said was legal advice on accounting standards.

While all three companies claimed to have hired Cohen to offer different types of expertise, overall, the work looked a lot like lobbying.

That is also how it reportedly looked to employees at Novartis. "Cohen promised access to not just Trump, but also the circle around him," one employee said in an interview with Stat News. "It was almost as if we were hiring him as a lobbyist."

Almost – but not quite. At the time they hired Cohen, soon after Trump's inauguration, both Novartis and AT&T already had scores of registered lobbyists in Washington who were working on the same issues that Cohen was hired to handle. These lobbyists, however, were required to disclose their work to the public under the 1995 Lobbying Disclosure Act.

In 2017 alone, 112 individual lobbyists from 34 different firms, including AT&T's in-house team, reported lobbying to advance the telecom giant's policy goals. Another 85 lobbyists representing 15 different firms disclosed that they had lobbied on behalf of Novartis.

The millions that Cohen was paid because of his perceived proximity to the president is a glimpse into the shadowy world of unreported lobbying.Brendan FischerCampaign Legal Center

Yet if one were to enter Cohen's name into a search of the same lobbying disclosure database where the above information is stored, it would come up empty. That's because Cohen is not a registered lobbyist, and he never has been.

"The millions that Cohen was paid because of his perceived proximity to the president is a glimpse into the shadowy world of unreported lobbying," said Brendan Fischer, chief counsel at the Campaign Legal Center, a nonprofit group which has filed a number of complaints against the Trump administration.

Revelations about Cohen's work for corporations this week have prompted many to ask the same question: Why isn't Cohen a registered lobbyist?

Neither Cohen nor his attorney replied to a request for comment from CNBC for this story. But the answer to this question of why Cohen didn't register as a lobbyist rests on precisely what it was that Cohen was doing for his corporate clients.

Lobbying 101

To meet the definition of a lobbyist, the law says a person must meet three criteria:

- First, he or she must be getting paid by the client for their work.

- Second, to be considered a lobbyist, he or she must make at least two contacts with government officials on behalf of the client. These contacts can be in the form of phone calls, emails or meetings, and they need not be to the same government official both times. So if one were to contact two different senators on behalf of a client, that would count as two contacts.

- The third threshold is often the murkiest: In order to be acting as a lobbyist for a client, the act of contacting government officials must take up at least 20 percent of the overall work that person does for this particular client.

For example, if a lawyer were hired by a company to do a year's worth of full-time legal work, and he or she happened to make two phone calls to lawmakers to discuss the client's agenda during that year of work for the client, this would most likely not be considered lobbying, because it wouldn't meet the 20 percent threshold.

"It is commonplace for well-connected consultants to evade lobbying registration by merely offering 'strategic advice' and carefully avoiding the 20 percent threshold," said Campaign Legal Center's Fischer.

Cohen's clients

These contacts lie at the heart of what it means to be a lobbyist, and it is not clear that Cohen actually contacted any officials to help press the interests of the companies that hired him. On the contrary, both Novartis and AT&T scrambled this week to distance themselves from Cohen by claiming he had done limited work for them – especially no lobbying work.

"Our contract with Cohen was expressly limited to providing consulting and advisory services, and it did not permit him to lobby on our behalf without first notifying us (which never occurred)," AT&T said in a fact sheet CNBC obtained Friday. "We didn't ask him to set up any meetings for us with anyone in the Administration and he didn't offer to do so."

Novartis went even further to disavow Cohen, claiming that it had hired him to advise on "certain US healthcare policy matters" in February 2017, the month after Trump took office, and decided after just one meeting with him in March "not to engage further." The pharmaceutical giant also claimed that the only reason it paid Cohen the full $1.2 million for an entire year is because it was trapped by the contract it had signed with him.

Nonetheless, Cohen's engagements with the two companies help shed light on the wide range of non-lobbying services companies are willing to pay for in order to gain a perceived advantage over their competitors.

"People pay law firms, lobbyists, other individuals to help them navigate the muddy waters of Washington politics every day. And it is not captured within the lobbying disclosure requirements or any other laws," said Meredith McGee, executive director of the nonprofit government watchdog group Issue One, in an interview this week with NPR.

"If [Cohen] does not meet the requirements to register as a lobbyist, then he's simply engaging in the selling of access to the administration," McGee said. "And that is not against the law."

Political intelligence

In Washington, the polite term for what McGee called "the selling of access" is "political intelligence." And companies are often willing to pay much more for it than they are for even top-tier lobbying services.

Consider the fees that Cohen charged his major clients: $600,000 for AT&T and $1.2 million for Novartis, each deal for a year. In the D.C. lobbying industry, this kind of money is more in line with what a foreign autocrat or a scandal-plagued organization might be expected to pay someone to take them on as a client, not what a Fortune 500 company like Novartis or AT&T would be charged.

To wit, a CNBC review of the lobbying fees that AT&T and Novartis reported paying in 2017 revealed that both firms paid Trump's attorney more than they paid any of their outside lobbying firms. A lot more.

According to data compiled by the Center for Responsive Politics, Akin Gump, the highest paid outside firm that lobbied for AT&T last year earned $400,000, or $200,000 less than the company paid Cohen. At Novartis, the highest paid outside entity was a boutique health-care firm, Tiber Creek, which was paid $240,000 -- just shy of a million dollars less than the drug maker paid Cohen.

The comparison is even more striking given that some of these lobbying firms list a dozen or more individual lobbyists in Washington who worked on the AT&T and Novartis accounts. Cohen, meanwhile, runs a one-man shop in New York City.

"The amount these companies paid Cohen shows the perceived value of political intelligence to multinational corporate interests," said Fischer of the Campaign Legal Center. "Even the smallest bit of inside information about a powerful political figure can give a company an advantage when they are trying to promote their interests with the government."

Risky business

Still, engaging in unregistered lobbying -- or political intelligence, or selling access -- is not without its risks, as AT&T and Novartis learned this week.

Within days of the payments becoming public, both companies were forced to admit that hiring Cohen had been a mistake, and they both expressed regret over the move.

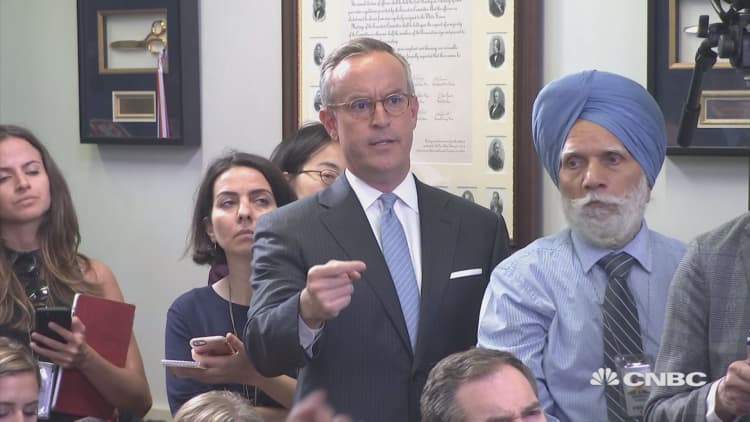

At AT&T, the senior executive in charge of the contract with Cohen, longtime lobbyist Brian Quinn, was reportedly forced into taking an early retirement, which the company announced on Friday.

Elsewhere in Washington, a nonprofit watchdog group, Public Citizen, submitted a formal complaint against Cohen to the Justice Department and to congressional offices that oversee lobbying registrations.

According to the complaint, Cohen "has actively solicited clients based on his access to Trump and administration officials; received exorbitant payments from foreign and domestic clients with business pending before the administration; and he has also provided ample yet unspecified services to his clients in exchange for those payments."

Cohen's attorney declined to comment on the complaint.

In the long run, however, this week's scandal over Cohen's influence peddling is not likely to have much of an impact on Washington's shadow lobbying industry, or on the web of influence buying and selling that extends from K Street to political campaign funding to members of the president's inner circle.

"The average American can't afford to pay six-figures to get inside information on how to influence government officials, and they can't afford to make huge contributions to campaigns and super PACs to buy access," said Fischer, of the Campaign Legal Center.

"Cohen's slush fund is particularly unsavory, but it isn't entirely unique," Fischer added. "It is an example of how our political system is tilted towards the interests of the wealthy and well-connected."