He argued that the Fed's inflation record over the past 15 to 20 years has been as good as or better than central banks in Europe that have only a single price-stability mandate.

In keeping one eye officially on unemployment, the Fed is unusual in a developed world where central bankers are typically tasked solely with maintaining price stability.

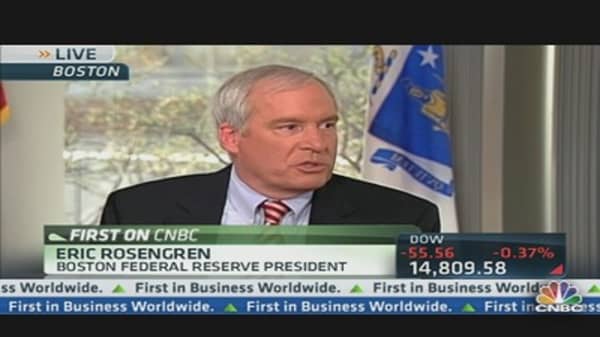

Highlighting the records of the European Central Bank, the Bank of England, and Sweden's Riksbank, Rosengren went so far as to suggest that central banks that focused only on inflation may want to consider adopting a U.S.-style dual mandate.

He said such a move, for example, would make it easier to publicly explain buying bonds when inflation is running above target, as that trio has done in the wake of the global recession.

(Read More: Time to Scale Back Easy Money: Fed's Plosser)

"The dual mandate in the United States has been criticized by some for providing an inflationary bias. However, the data show little such evidence," he told the conference on fulfilling the U.S. central bank's mandate of full employment, for which it aims along with a 2-percent inflation target.

"The dual mandate in the United States has provided a clear and transparent way to communicate the need for aggressive monetary policy."

Conservative politicians and hawkish economists have at times criticized the Fed's "full employment" mandate in large part because the main monetary policy tool, the short-term interest rate, has only an indirect effect on the labor market.

These criticisms have grown as the central bank has rolled out increasingly easy policies, including three big bond-buying programs.

Yet while the Fed has eased policy to lower joblessness and raise inflation in the wake of the 2007-2009 recession, central banks such as the BoE have also launched accommodative bond-buying programs despite higher-than-desired inflation rates.

With a touch of levity, Rosengren said that may only prove that "all of us are dual mandate banks at heart."

(Read More: Unlike the Fed, BOJ's QE Won't Unleash Hot Money)

Could Have Been Easier?

The Fed is buying $85 billion in Treasury and mortgage securities per month and has promised to keep interest rates near zero for a long while more to support the stop-start U.S. economic recovery and get Americans back to work.

The unemployment rate was 7.6 percent last month, higher than the 5 to 6 percent range to which Americans are accustomed. Rosengren told CNBC he's hopeful for a rate of 7.25 percent by year's end—reached through payroll employment growth, not withdrawals from the labor force. "It may be appropriate at that time to either taper or stop our purchase program," he said.

On the other side of the mandate, the Fed's preferred measure of inflation is below target at around 1.3 percent.

While policy doves like Rosengren currently hold sway over Chairman Ben Bernanke and the majority of Fed policymakers,minutes from last month's policy meeting suggest the quantitative easing program could draw to a close by year end, earlier than some economists had expected.

Rosengren however said there remains "strong rationale for continuing our highly accommodative monetary policy," and he predicted inflation will remain "well below" the 2-percent target over the next two years, paving the way for more easing. "Inflation is still quite well-behaved," he told CNBC.

Doubling down on his stance, he said the fact that the United States has historically had a tighter inflation range and broader unemployment range than that of the euro zone, Britain and Sweden suggests the Fed could have been even more stimulative over the past five years.

The Fed struggled with runaway U.S. inflation in the 1970s and early 1980s. Since then, Rosengren argued, the main difficulty has been maintaining full employment, including a run-up to 10 percent joblessness in 2009.

"This may indicate that during the period of the 1970s and early 1980s too little weight may have been placed on inflation misses but in the more recent past we may have placed too little weight on unemployment misses—and if anything, we should have acted more aggressively to reduce the unemployment rate," he said.