The British already have a foothold in the manufacture of small satellites. Now they are moving quickly to build the rockets necessary to launch them.

The United Kingdom Space Agency, working with British companies in the sector, has established how intends to grow its 6.5 percent stake in the $350 billion space economy over the next 12 years.

"We want to get to a place where the U.K. has 10 percent of the global space economy by 2030 and we're working in partnership to deliver it," Claire Barcham, the director of the agency's satellite launch program, told CNBC at the 34th Space Symposium in Colorado Springs, Colorado.

A 10 percent stake could be worth more than $109 billion in 2030, according to Bank of America last year.

To achieve that growth, UKSA is working to attract rocket companies which specialize in launching small satellites, Barcham said. The U.K. currently produces about 44 percent of the world's small satellites and has extensive facilities to operate those satellites once active. But Britain lacks any spaceports or launchpads to put the satellites in orbit.

"The one bit that we're missing is the launch," Barcham said, adding that UKSA wants "to use launch capabilities to make the U.K. the European hub for small satellites."

In the next couple of months, the agency is expected to announce funding grants worth millions for the development of launch facilities.

"We're conscious of the need to move quickly. There is a lot of focus on the crystallization of demand from 2020 on," Barcham said.

The small satellite attraction

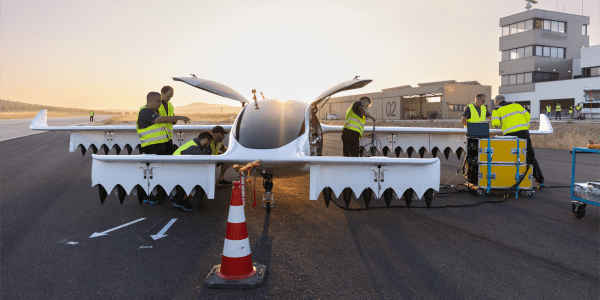

The UKSA's hope is that launch facilities will attract a host of launch providers to Britain, including traditional rockets launching vertically, new air-launch systems or point-to-point transportation systems for high-speed travel around the world.

"There are British companies that are looking to build new capabilities [such as] Skyrora, Orbex, Orbital Access. Companies in the U.S. that have a great amount of launch heritage … like Lockheed Martin [or] Orbital ATK. And then you have the new engines on the market: Virgin Orbit, Virgin Galactic," Barcham said.

The light-class rockets designed to launch small satellites command a premium because they launch often, quickly and directly into specific orbits. That can shave months off the time it takes a satellite to become operational.

Locations under consideration in the U.K. are located much further north of the equator than most of the world's launchpads, offering a unique ability to reach orbits commonly used by small satellites.

"The U.K. is incredibly well placed," Barcham said. "If you're looking at vertical launch options, the north of Scotland has a really clear access to the most popular orbits for small satellites."

Barcham believes as many as 80 percent of future small satellites will require these orbits. Combined with Britain's robust satellite production and operations ecosystem, the location means launch is the "one bit that we're missing," Barcham said.

"We've heard a lot from our small satellite sector that access to space is one of the things that holds them back. It's expensive, it's cumbersome," Barcham said. "We can be a one-stop shop for all requirements on the supply and on the demand side."

Raising the regulatory bar

Partnerships are a focus for the UKSA, especially when it comes to funding and regulations. Barcham emphasized that the grants are not intended as a way for the U.K. government to direct the market's growth.

"This is about seeding the market and kick-starting activity," Barcham said. "Unlike other countries around the world, what we're not doing is running a government facility, we're not procuring a government service."

She wants the UKSA's regulations to be the most modern in the world and sees the current environment as a clear opportunity to write more-user friendly licensing rules. Regulations "in a number of countries doesn't really cater" to a rapid launch cadence, Barcham said, and instead has "a lot of cumbersome heritage."

"We really want to make it user-friendly," Barcham said, noting that one thing the agency has heard "is the involvement of multiple different regulators in a single country … makes things really confusing."

While three different UK bodies that have authority to regulate commercial space, Barcham said UKSA does not "want to have license applicants try to work out which body they need to try to apply to and deal with multiple different processes."

UKSA is instead testing a website which acts as an application portal. The government would then sort out which parts of a license need to go to which regulatory authorities, so companies would only deal "with one simple interface," Barcham said.

The U.S. is attempting to fix similar flaws in its own regulations. As SpaceX and others have slammed existing space regulations, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross announced further details Tuesday about how his department intends to become "a one-stop shop" for regulations.The Commerce Department plans to work with the existing regulations enforced by the Federal Aviation Administration and Federal Communications Commission, Ross said.

WATCH: Virgin Galactic spaceship Unity takes first supersonic rocket flight