Peris Bosire and Rita Kimani should by all rights have had venture capitalists knocking down their door. Computer science graduates of a top university, they have a growing fintech start-up with a product that could reach 50 million people. Oh, and their idea could help feed the world, or at least a continent.

But there are a couple of problems: They are women, and they are in Kenya, which most of the world's venture capitalists see as risky. Hardly any venture capital flows to women anywhere.

"It's hard to convince a male CEO of a bank to listen to you," said Bosire, whose company, which lends money to farmers, is called FarmDrive. "People say, 'OK, the two young girls are coming,' and not in a nice way."

The tide is beginning to turn, however. Money is pouring into a new kind of investment strategy — impact investing — aimed at finding and reaching companies like Bosire's, with ideas that could help solve some of the world's most intractable problems.

In 2017 an estimated $139.9 billion was invested in impact investment strategies (more recent numbers aren't available), up more than 10-fold since 2014, when the amount was $10.6 billion, according to the Global Impact Investing Network. (Estimates for the amount currently investing in impact strategies vary.) In February $6 trillion BlackRock, the world's largest asset manager, announced it was getting into the game. It said it would launch many more impact investment products under one umbrella, led by former Robin Hood Foundation president Deborah Winshel.

Setting the investment bar higher

The size of the potential market for impact investments is huge. Right now people who want to invest according to their consciences do so through socially responsible funds, which mostly exclude entities like oil companies or gun manufacturers. There was $8.72 trillion invested in SRI strategies in 2016, according to the Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment.

Impact investing is different in that it sets the bar higher. Impact investors want to make decisions based on risk, reward and on the amount of "good" an investment produces in the world. Wall Street firms will have to adapt by considering and communicating much more information about investee companies, like: Where are they headquartered? What problem are they trying to solve? Who will benefit, and who will be hurt?

More from Global Investing Hot Spots:

Iran's economy may be headed for a death spiral

Saudi crown prince begins building tech hub

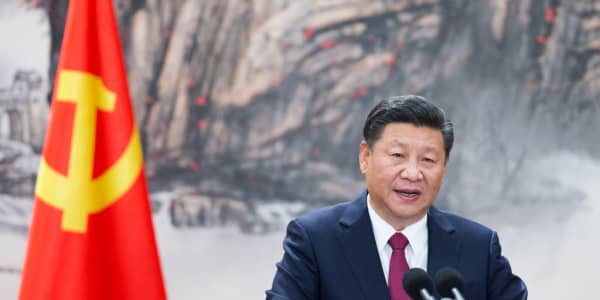

China's $1.2 trillion weapon that could be used in a trade war with US

Impact investing is growing fast. But what looks like an overnight success is hardly that. The revolution has been quietly led for more than a decade by a handful of advocates, including many women. Prominent among them is Jean Case, the wife of AOL billionaire Steve Case.

In her eyes, stories like Bosire's are the germ of a real investment revolution — one we're only beginning to see. Her goal is to redirect some of the fire hose of capital to markets, like Kenya or many others across the world and the United States, where it's now a trickle. Empowering entrepreneurs in those spaces will produce more and better business ideas to help the planet, she argues.

In the case of Bosire, in Kenya, her idea came from growing up as the daughter of smallholder farmers. She saw firsthand that because they lacked capital to invest in equipment or fertilizer, smallholder farmers couldn't make their land more productive. They've given up on seeing that as a business venture," she said. "We saw a way to change that."

One of Case's arguments is that NOT investing in ideas like Bosire's is risky.

"We need to redefine risk," she said to a roomful of elite investment managers in New York in February. What will happen if we don't start finding and funding the smart solutions to problems like poverty in Africa, climate change, or nutrition in America?

"What if you don't have two rich friends across the hall, if you don't have Daddy, who gives you $25,000 and your friends-and-family raise?" she said in an interview. "It's critical that we find (poor entrepreneurs) and we build hubs and accelerators around them so that if they don't have friends and family, they have a path forward to use."

Changing Wall Street perceptions

Ultimately, Case hopes that by forcing Wall Street companies to consider not just excluding "bad" investments but including good investments — good being measured by real, scientific criteria — she can reshape finance.

"In 1970s and '80s (venture capital) was the Wild West," Case said. "Traditional finance said, 'Stay away from that; nobody knows what it is; it's chaotic; it doesn't have a complete ecosystem.' Then what happened? A few big hits and suddenly pension funds are allowed to come in and new data emerges. Suddenly the investors feel comfortable."

So far, women and millennials have shown the most willingness to experiment with impact investing. Both groups have shown they are willing to sacrifice percentage points from their returns to invest in companies and projects that do good in the world.

The short track record of impact investing shows that investors need to be willing to make sacrifices for the greater good: The 15-year annual average return on 70 private equity funds in the Cambridge Associates Impact Investment Index was 6.10 percent, compared with 10.04 percent over the same time period for the S&P 500 and 12.86 percent for the MSCI Emerging Markets Index.

Female evangelists

Case is one of the most prominent voices in the United States for impact investing, joining a small but influential group of investors worldwide, including Nancy Pfund, managing partner of venture capital firm Double Bottom Line. Liesel Pritzker Simmons, an actress and heiress to the Hyatt Hotels fortune, is another. Her firm is called Blue Haven initiative. Outside the United States, Marilou van Golstein Brouwers of Triodos Bank is considered another leader in the space.

Case stands up for the concept of impact investing even more than her billionaire husband, AOL founder Steve Case, who promotes venture capital investment in entrepreneurs in smaller U.S. cities through his Rise of The Rest Tours. But Jean Case argues for a worldwide view of impact investing and for supporting entrepreneurs as well as investing in them.

Wealthy in her own right as a former senior executive of AOL, she has paid for research, helped found a think tank, the Beeck Center for Social Impact & Innovation, and shifted her own investments to an impact model — though a spokesman refused to disclose how much. Recently, as chairwoman of the National Geographic Board of directors, she helped decide to shift $50 million to impact strategies. Mike Ulica, the interim president and CEO of the National Geographic Society, said the organization shifted a relatively small portion of its nearly $1 billion endowment to impact strategies because it's difficult to find opportunities that meet the organization's return needs of at least 4 percent a year.

"Jean was a catalyst in getting the conversation going," he said.

Along with BlackRock's announcement, there are more signs she and others are making headway. The Ford Foundation announced recently that it would shift $1 billion of its endowment to impact strategies, for instance.

Case argues that eventually impact investments can be competitive on returns with traditional investments, as fees come down and as an ecosystem that enables more exits is born. Case often pushes her agenda among the nation's wealthiest people.

"Through the Giving Pledge community ... she's influenced many people with wealth to think critically about what their capital is doing in the world. Perhaps even more importantly, I've seen Jean quietly and persistently lead by example behind the scenes trying to align her own portfolio with her values over the last few years," said Ross Baird, author of Innovation Blind Spot and co-founder of Village Capital, a firm that trains and funds entrepreneurs solving global problems.

Spreading the idea of impact investment is a big challenge, however. In an interview in the fall, for instance, Vanguard founder Jack Bogle noted that investors could sacrifice risk-adjusted return to do good but ought to weigh carefully the amount of money they're giving up over a long time period in portfolios. "That's a personal decision, I guess," he said.

It's one thing for wealthy people to jump into an unknown investment strategy; it's another for pension funds or smaller individual investors to do so, though a real movement needs much more volume than the current total. There are others in the philanthropic world who argue that if impact investing takes resources away from nonprofits, it will have a net negative effect in the world.

In Europe, a different approach

Some argue investors might eventually see higher or at least equal returns with impact investments. A $500 million Sweden-based fund called Summa Equity looks for companies that are "future proof," built to solve problems such as rising population, changing climate and to take advantage of trends in technology. Summa focuses on Scandinavia, investing in companies such as a salmon processor. Salmon processing is a good investment, and good for the planet, because only about 1.3 kg (2.8 lbs) of fish food produce 1 kg (2.2 lbs) of salmon, with no carbon dioxide emissions.

"We told our investors that we expect higher returns in a volatile and risky world by investing in companies that address these problems," said founder Reynir Indahl. Making that case might be easier in the Nordic countries, where "it has always been very important that you build a society that works."

Summa hasn't had any exits yet, but Indahl noted that so far it has been able to take majority ownership in companies where the owners stay on, which is a significant advantage. It expects average net returns of higher than 15 percent, with a typical 2-and-20 fee structure for most limited partners.

Is women's leadership being supplanted?

Meanwhile, it is somewhat galling that impact investing — whatever name you give it — is taking off now that men have taken up the cause. Larry Fink, founder of BlackRock, grabbed headlines when that firm announced its big commitment to impact investing, admitted Lisa Hall, senior fellow at the Beeck Center.

"What I would like to think is that he got the headlines because of the size and scope," she said, but acknowledged the possibility that, in the male-dominated world of finance, the presence of women in the field has actually contributed to it being dismissed.

"There are some who try to pigeonhole impact investing because it's attracted a lot of women. It's a new type of investing, where you could make a name for yourself."

None of this is unfamiliar to Case. Reared by a single mother, Case went to a private school on a scholarship and was dismissed because of that. "I was always 'the scholarship student,'" Case said. Asked what stories move her the most, she said, "the stories the world writes off, the stories that come around to prove … you had no idea what you were writing off."

Back in Kenya, meanwhile, Bosire and Kimani have added yet another line to their résumés that ought to appeal to investors: They are working with Safaricom, Kenya's huge telecom, in a program to lend to farmers and gather data about their creditworthiness. As of a few months ago, the company had already reached 372,000 farmers and has approved 6,000 loans to some of these farmers. The aim is to reach 3.5 million in five years, all of whom will have access to input loans through FarmDrive's alternative credit-scoring model. The hope is that eventually banks will better understand how to lend to small farmers and see them as less of a risk.

Even that kind of success, however, doesn't mean FarmDrive is a shoo-in to attract investors, especially those from Silicon Valley and elsewhere abroad. Bosire is considering seeking a round. "There has to be a way to support people's business, and in our case the business of the community of farming," she said.