Fred DeLuca might be the closest example to the quintessential “American Dream” in action.

When he was 17, DeLuca borrowed $1,000 from a family friend to start a sandwich shop, with the goal of paying for college. That was in 1965.

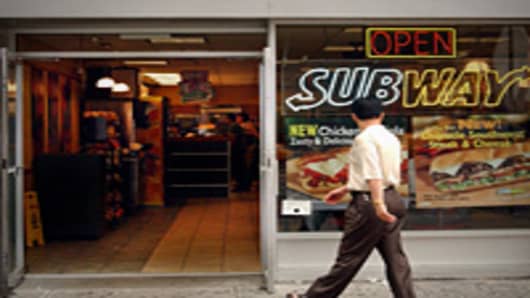

Today, his humble shop — Subway — is the largest sandwich franchise in the world, with 34,000 locations in 94 countries and sales of more than $13 billion in 2009 alone.

Not bad for a teenager from Brooklyn with a dream to make delicious sandwiches at an affordable price.

DeLuca remembered his family friend, Peter Buck, telling him that starting a small business would be easy: “You rent a little store. You build a counter, buy some food. Open for business and customers will come in. You'll have all the money you need,” he recalled Buck saying.

But, of course, it wasn’t that easy.

DeLuca struggled with meeting his goal of opening 32 stores in 10 years. He made it there in 11 years, but it was a difficult, one-store-at-a-time process. The turnaround came in the company’s eighth year when, realizing he was behind schedule on store openings, DeLuca decided to shift gears toward franchising.

“That really, really helped quite a bit because we taught people how to run Subway shops,” DeLuca said. “By then we had lots of experience. We developed great systems. We basically took these systems, packaged them up, and taught people in their own neighborhoods how to open stores and run them.”

According to Andrew Liveris, chairman and chief executive of Dow Chemical and author of the recently published “Make It in America,” teaching sustainable business skills, as Subway has done with its franchisees, is one of the keys to reviving the U.S. economy.

He said American companies opt to outsource manufacturing to other countries, our workforce eventually loses the skills and technological edge to produce entire groups of products, thereby falling farther behind.