Last month, a dozen topless Venezuelan women gathered in front of the Caracas Museum of Contemporary Art in protest. Yet they weren’t rallying for women’s rights or equality; instead, they were standing their ground for the sake of stolen art.

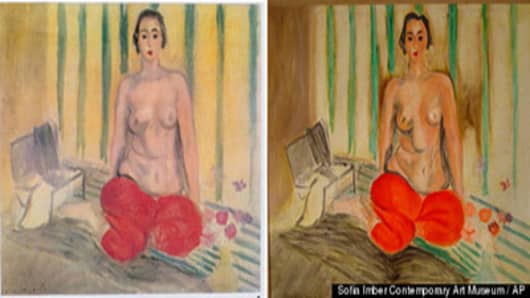

The half-clothed women (warning: explicit content) demanded the U.S. return a $3 million-dollar Henri Matisse painting, reported stolen from the Caracas museum in December 2002. The “Odalisque in Red Pants” had not been seen in public, until undercover Federal Bureau of Investigation agents recovered it during a sting operation in Miami Beach on July 17.

According to recent U.S. Justice Department statistics, art crime is an industry estimated at $6 billion — surpassed only by drug and gun trafficking trades.

Watch “Crime Inc: Art for the Taking” to learn more. Tonight at 9p ET/PT on CNBCIn the case of the Matisse painting, Miami-based Pedro Antonio Marcuello Guzman and Mexico City resident Maria Martha Elisa Ornelas Lazo allegedly tried to sell the painting for $740,000 -- a fraction of its value -- before they were arrested. They were indicted for conspiracy to transport and sell stolen property, facing up to ten years in prison if convicted at their trial in November.

Citing the pending trial, the U.S. Attorney’s office declined to comment on how it would dispose of the Matisse painting. However, former FBI Special Agent Robert Wittman, who served as an art theft specialist for two decades and is familiar with the case, had his own ideas.

“The U.S. has no interest in holding onto the painting," Wittman said, even though authorities need it in the short-term for evidentiary purposes. "It depends on the U.S. Attorney’s office how they want to proceed, but I’m confident it will be returned to the Venezuelan Embassy."