Discussions on the future of work tend to be aspirational — workers can live where they want, work how they want, for whom and when they want. The benefit of this new collaborative but disparate workforce for companies is that they gain the ability to scale business quickly with just the right talent, filling specific niches. It's a win-win. Workers are happy, and companies get what they need ... in theory.

Unfortunately, talent shortages have become the top emerging risk organizations face, with large companies struggling to fill technology positions, revealed a recent Gartner survey. Approximately 918,000 unfilled IT jobs were listed in the U.S. over the last three months alone, as tech job postings continue to rise. By 2030 the global demand for skilled workers will exceed supply by more than 85.2 million workers. This translates to $1.748 trillion in lost revenue for U.S. companies, or roughly 6% of the economy, according to global organizational consulting firm Korn Ferry.

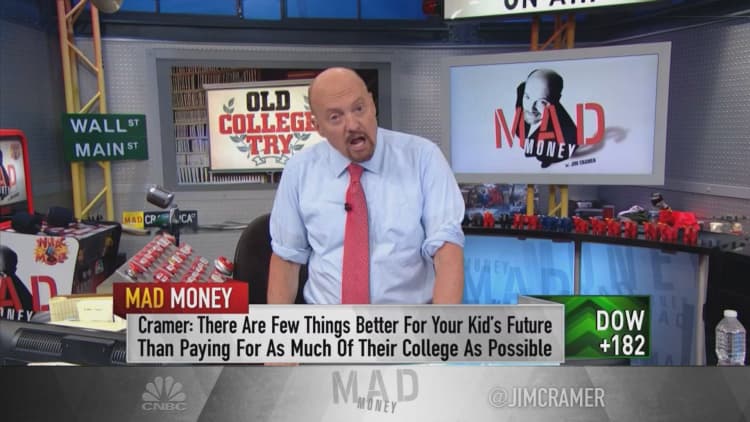

Yet to have the greatest, most agile, most modern workforce in the world, to live in a better America, to embrace the future and solidify our position as a technology superpower, we have to have qualified workers that push the future of work forward. And the only way to do that is to hold our higher education responsible for the real-life outcomes of its students, equipping the workers of tomorrow with the necessary, relevant skills for success rather than simply handing them a paper diploma and wishing them well.

For more on tech, transformation and the future of work, join CNBC at the @Work Summit in New York on April 1–2, 2020.

On top of this, there must be a solution to the ballooning student debt crisis ($1.6 trillion and counting), which affects tens of millions of Americans and further threatens future economic prospects. Workers must be able to access skills-based training without digging themselves into an insurmountable financial hole.

Within this context, let's consider how the present crop of presidential candidates propose to solve these problems.

Treating the symptom, not the disease

Former Vice President Joe Biden says that as president he'd lower student loan payments for people in income-based repayment plans. Bernie Sanders wants to erase all of the $1.6 trillion of outstanding debt and make public colleges tuition- and debt-free. Elizabeth Warren would cancel $640 billion of the debt and eliminate tuition and fees at public colleges. Pete Buttigieg wants to expand Pell grants. Kamala Harris and Cory Booker have endorsed using federal matching grants to incentivize states to invest more in two-year and four-year colleges.

While these candidates should be applauded for shining a light on the problems associated with student loan debt and the flaws in the modern education system, these plans all have one major thing in common: They're focused on treating a symptom — that is, the large, burdensome debt load of American college and university graduates. But they're failing to treat the underlying disease — providing a higher-education system that's worth paying for and is held accountable for turning out students with the essential talent necessary to work for today's employers.

Current proposals instead present surface-level solutions that ignore the underlying root cause of the student debt crisis: the misalignment of expectations between schools (subject matter mastery) and their students (acquisition of skills to get a good job). This mismatch affects students' ability to fully participate in and help cultivate the future of work. This is not a problem isolated to the technology industry. It's systemic.

Even within academia, less than half of faculty members at four-year colleges and universities thought school readied them for their jobs. We must demand more cohesion between the acquisition of knowledge and application of skills to future careers because the ultimate cost is too high — America's economic competitiveness is at stake.

3 ways to hold higher education accountable

Moving forward, one thing is clear: Resolving the student loan crisis and gaining a qualified workforce will not come from "free" college (after all, free college is never really "free"; it would likely be paid for via higher taxes). It instead will require providing an education that aligns the interests of schools with not only their students but future employers as well — and hold higher education accountable for the practical results of graduates.

Here are three ways this can be achieved.

1. Make alumni performance the measure of school quality (aka reform accreditation around workplace outcomes of graduates). The US doesn't have an official minister of education quality control, so it relies on an outside accreditation system. The federal government uses this system to determine whether tuition is worth the cost.

The government has the power to demand that schools begin placing more weight on the employability or real-life workplace outcomes of their graduates. ... Schools should be judged on how well they help students live up to their hiring potential.

There are a lot of problems with the current system, such as the fact that quality varies widely from school to school, and different accreditors use different ways of measuring school quality. However, because the government is the biggest, most important customer of these accreditors, it has the power to demand that schools begin placing more weight on the employability or real-life workplace outcomes of their graduates. This doesn't mean schools have to be, or even should be, judged on how much money their students make when they graduate. It means that schools should be judged on how well they help students live up to their hiring potential.

2. Embrace ISAs. Income-Share Agreements are probably the single most effective way to embrace a market mechanism to foster accountability of schools to their students. Whether it's a President Biden, Bernie or Booker, we know that as long as schools continue getting tuitions paid, regardless of the employability of their graduates, we risk perpetuating the debt crisis. ISAs take aim right at it.

It works like this: Trade schools or colleges make an agreement that students will share a percentage of their salary only when they find a job after completing their program. The amount can range from 7% to 20% of the graduate's income — and only for a limited period of time, usually from one to five years. Think of it as a built-in mechanism where students share part of their success to fuel the next generation of students and ongoing health of the workforce.

ISAs prove that students don't have to live with debt their whole lives. They have been pioneered successfully in Europe and Australia, and are now increasingly being embraced in the United States. Among others, Purdue University offers ISAs, so does Clarkson University and the University of Utah. And this September, UC San Diego began offering an ISA program. Schools only get paid if their students succeed professionally so the incentive to train people for the future of work is quite high.

3. Get employers more involved. The pace of new skills needed on the job is fast and getting faster. Consider that most of the in-demand skills today — like mobile software development, AI, 3-D printing, nanotechnology — barely existed a decade ago. Skills prioritized today likely will not be the same ones tomorrow. In fact, according to a 2016 World Economic Forum report, 65% of children entering primary school will end up in jobs that don't yet exist.

With that kind of skills churn, curriculums need to be constantly updated, and employers are uniquely positioned to help schools anticipate the rapidly changing jobs market to come. After all, employers are the direct beneficiaries of a skilled labor force. They should step up their involvement and investment in preparing students and workers for the future.

The United States has been the world's technological leader over the last half century because of its investment in human capital. The continued viability of the country's technology-driven economy and the future of work will depend on the quality of human capital more than ever as talent wields its own currency. Making schools effective and economically accessible is vital for success.

Now is the time to hold schools accountable to students. Who will move beyond aspirations and step up to embrace actual tactics to improve the workforce? Who will do what is necessary to preserve economic stability? November 2020 in just one year away. It won't be long before we find out who truly champions the future of work with policies to strengthen and preserve the talent pipeline.

—By Sylvain Kalache, co-founder of the Holberton School