If you want to get a close-up view of how the coronavirus pandemic has taken its toll on America's health-care system, just look at Christ Hospital in Jersey City, New Jersey, one of the nation's earliest hot spots. For the past three months this 375-bed facility has had to cope with a flood of Covid-19 patients, mounting deaths and a stalwart workforce stretched to the limit.

"This was the harshest and most difficult time of my career," says a nurse who works at Christ Hospital who wished to remain anonymous. "Many days we were severely understaffed, and had to work long hours to keep up with the surge. So many patients were dying, and we were the only ones their to hold their hands in the end. All of us are still traumatized."

"We've never seen so much death," said Dr. Tucker Woods, chief medical officer. The numbers might have been higher if he and Christ's other leaders hadn't taken swift action to transform the hospital into a MASH-type operation. By mid-March, Christ Hospital had trained a core team of physicians and nurses to treat patients in designated units, established procedures for reusing dwindling supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) and erected an outdoor triage center.

But nurses and other frontline staff say these measures were not nearly enough. It has led local No. 5186 of the Health Professionals and Allied Employees (HPAE) union in New Jersey to file an OSHA complaint citing workplace safety hazards against the hospital in early June. The complaint alleges that the hospital gave the staff counterfeit, nonapproved masks and respirators, did not properly train staff on how to don and remove PPE to avoid Covid-19 contamination and did not keep a log that recorded employees who contracted the illness or a record of their follow-up medical treatment.

These are claims chief hospital executive Marie Duffy says are untrue and that the hospital plans to dispute. Christ Hospital is not alone. The health-care facility is one of 16 under OSHA investigation in New Jersey, according to the HPAE.

At the same time, an existential threat was looming — a contentious acquisition deal that could lead to the hospital's closing altogether.

That's ironic, considering how much the community needed the hospital during the worst pandemic in a century. But the health-care sector has been among sectors hardest hit during this recession, with more than 1.4 million workers suddenly without jobs. Thousands of hospitals are at risk of closing in the months ahead, especially those in rural areas and small towns, according to Chartis Center for Rural Health. Even with money from a $175 billion bailout, many hospitals such as Christ Hospital are facing critical cash shortages because they have had to cancel the elective procedures they rely on to make money.

The emotional siege

Despite the challenges, rather than eliminating jobs, Christ Hospital's leaders reconfigured its workforce of about 1,100 employees and redeployed hospital resources. They reassigned medical staff to direct therapy trials to work in a crisis-management "war room" and to assist in diagnostic labs. They established a "proning team" of nurses who turn ventilated patients to improve oxygenation. They recruited personnel to operate a makeshift morgue.

All the while, Christ's leaders also are addressing the emotional toll the crisis has taken on everyone. They don scrubs and tour the ICUs to comfort overwhelmed frontline providers and boost morale. They launched a "warm line" for traumatized staff to call. If an employee tests positive for the coronavirus and needs to take time off, management ensures they're appropriately paid.

Woods claims these changes have circumvented any moves to downsize. "Christ Hospital has not laid off or furloughed any employees," said Woods. Although a portion of its workers took voluntary leaves of absence or chose to resign rather than risk exposure to the virus, there have been no shortages of doctors and nurses, added Duffy. "All clinical staff were reassigned and repurposed," she said.

"But many nurses at the hospital are upset they haven't received hazard pay for risking their lives during this crisis," says Nicole Nankowski, an ICU nurse and president of HPAE Union local No. 5186 in Jersey City. It's an issue the union has raised with hospital management. According to Duffy, a lack of funds has made it hard to do. Instead, the hospital gave workers $50 Shop Rite gift cards for food.

A crash course on crisis management

Christ Hospital is one of three for-profit New Jersey hospitals owned by Jersey City-based CarePoint Health. Christ serves a diverse, largely minority population in a city of roughly 265,500. It is designated a safety-net hospital, meaning it provides health care for individuals regardless of their insurance status or ability to pay — an already vulnerable demographic that has been disproportionately impacted by the coronavirus pandemic.

But nothing could have prepared the hospital staff for the sudden influx of sick and dying patients. As of June 1, Christ Hospital had admitted a total of 808 patients who were either diagnosed with Covid-19 or under investigation for it, 173 of whom succumbed to the disease. That day, the hospital had 31 such patients, representing 41.7% of the inpatient population. "At our peak in early April, we had 142 Covid patients," Woods said, or 84% of all inpatients. "We're still drinking water from a fire hose, but it's much better than previously."

During the height of the crisis, physicians' caseloads were doubled and nurse-to-patient ratios went up significantly. PPE was a huge stressor, said Sara Vieira, assistant vice president of patient-care services, who oversees the nursing staff. "We were used to having so much PPE around, we never thought we'd run out," she said. "But in January we saw a fracture in our supply chain." Unsure when new deliveries might arrive, "I gave nurses a bag with an N95 mask in it and told them to use that for the day," Vieira said. Nurses also were instructed to wash eye shields with bleach until they couldn't be used anymore.

When the need for additional ventilators in the ICUs became critical, Duffy contacted the state's department of health. "By end of day, they dropped off five ventilators," she said. As the number of deaths rose, the hospital brought in refrigerated trailers to serve as temporary morgues.

Now the hospital is preparing for a new spike in cases due to the large protests over the police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the gradual reopening of the local economy. And that should continue in the fall as the flu season gets under way. To prepare, Christ Hospital has begun rapid, on-site coronavirus test analyses, established new screening and testing guidelines for staff and patients, instituted universal mask-wearing, is replenishing PPE supplies and will be installing thermal cameras at entrances to detect employees and patients with fever.

Navigating through a firestorm

Although mandatory social distancing guidelines have led to a massive drop in Covid-19 patients in the Northeast, many believe a new wave could appear in the fall.

The administration says they will be better prepared this time around.

"It's important to take a lead role and to prioritize work assignments," Woods said. You must be a good listener, too. "Sometimes doctors come into my office and cry, so listening to them is really necessary."

Duffy too has had to console many grief-stricken staffers while doing rounds on the floors and in the ICU during the crisis.

Clearly communicating a plan is vital, Vieira said, recalling Friday calls with nursing supervisors about leadership's plans for the upcoming week. "There may be some pushback, so I have to talk through the risks versus the benefits. I've often said, This is the best bad decision."

"In a crisis like this, you see characteristics come out from those who are strong and those who aren't so much," said Dr. Caitlin Jones, medical director of the emergency department. You find out who you can count on, or not. "My phrase is, 'Tough times don't last; tough people do,'" she said. "Buck up and get the work done."

In fact, some members of the Christ workforce quit or resigned for fear of having to care for Covid patients. "I cannot imagine ever hiring those folks again," Vieira said. "They left us in our time of most need. As a leader you have to go on with people who can pull you through."

"The true test of leadership is how you function in a time of crisis," Duffy said. "Outcomes are determined by leaders' actions, and our employees look to us and how we respond."

Duffy manages Christ's day-to-day operations — from staffing to tracking patients to monitoring expenses — a routine upended during the past few tumultuous months. In January, anticipating a Covid-19 surge, the hospital implemented its established disaster plan, implemented for past events such as the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks and Superstorm Sandy in 2012, and set up a command center, dubbed the war room. There, she and her fellow leaders coordinate daily plans and review reports from employees whom they've put in charge of critical issues, such as PPE inventory and patient discharges.

Sometimes doctors come into my office and cry, so listening to them is really necessary.Dr. Tucker Woodschief medical officer, Christ Hospital

"Times like this require consistent, accurate and constant communications with employees," Duffy said. To that end, she participates in 2 p.m. conference calls several days a week, during which various leaders update each other and field questions from doctors and nurses. "Knowledge is power, and when they have the information, it makes them a lot more confident."

Woods, formerly the ED director for the CarePoint network, began developing pandemic protocols in 2014, when West Africa's Ebola epidemic threatened the U.S. "We referred to those procedures, which definitely helped us prepare for the coronavirus," he recalled.

The key, Woods said, was putting together the core team to exclusively treat coronavirus patients. "Normally we have 40 to 50 physicians caring for admitted patients, but didn't want to train that many for Covid-19." So he reassigned a multidisciplinary group comprising six hospitalists (in-house doctors who see inpatients), 12 physicians and seven physician assistants from the emergency department and nine physicians from the intensive care unit (ICU), as well as about 40 critical-care nurses.

As the number of Covid patients escalated, Woods enlisted several private physicians from the community. In early March, Dr. Antonios Tsompanidis, Christ's chief academic officer, suggested conscripting a group of 38 interns, residents and fellows to further ease the core team's burdens. "They agreed to put their traditional medical education at a standstill," Tsompanidis said. "They're now working seven days on, seven days off, treating Covid patients either in the inpatient units or the ICU."

Woods had to assign other physicians to a range of vital jobs, confident they'd rise to the occasion. For instance, a family medicine doctor was put in charge of implementing Christ's use of convalescent plasma therapy, an experimental procedure that treats severe Covid patients with blood donated from ones who have recovered, on the premise that their antibodies will turn back the disease. "She's been the perfect person to run the program," he said.

He asked the director of respiratory therapy to help manage makeshift morgues retrofitted inside three refrigerated trailers Woods requisitioned as deaths mounted. Bodies have to be respectfully handled and lifted onto shelves 10 deep in each trailer. "It is physically and emotionally grueling and a huge logistical challenge," Woods said.

Throughout the pandemic, daily media reports from hospitals across the country have shined a light on the tireless efforts of frontline nurses. At Christ Hospital, Vieira marshals an army of about 500 nurses working in different medical services, but whose assignments to Covid-19 duty increased along with the number of infected patients.

"In the beginning, the emergency department and ICU nurses trained in critical care were the sole focus," she said. "Then we added the telemetry unit, and then another unit, until almost the entire building was dedicated to Covid-19 care."

Nurses from other services, such as surgery, endoscopy and same-day care, were idled when the hospital canceled scheduled elective procedures in March. "But it wasn't possible to make them critical-care nurses overnight," Vieira explained, "so we assigned them as runners to assist in Covid-19 units." They do everything from procuring medications from the pharmacy to answering phone calls from worried family members who can't visit their loved ones.

As coronavirus cases continued to grow, Christ Hospital tapped into the nationwide network of traveling nurses, recruiting about 20 critical-care specialists from as far away as Texas and Alaska. They were onboarded in hours instead of weeks and put right to work in Covid-19 units. "It's been one of the ways we've survived," Vieira said.

Although most of the medical and surgical units in Christ Hospital eventually were devoted to coronavirus patients, the emergency room was inundated early on. "This is a place with controlled chaos on a regular basis, but now there's just more chaos," Jones said of her domain, at one point 95% filled with Covid-19 patients, three quarters of them on ventilators.

The emergency department's physicians, physician assistants and nurses had to transition from treating heart attacks, broken bones and other emergencies to Covid cases. An unusual challenge, though, as more and more people started showing up, was differentiating individuals who actually were infected and symptomatic from the "worried well" who feared they were. Fortunately, Woods and Duffy anticipated the rush and opened the outdoor tent, which essentially became a screening area for the emergency room.

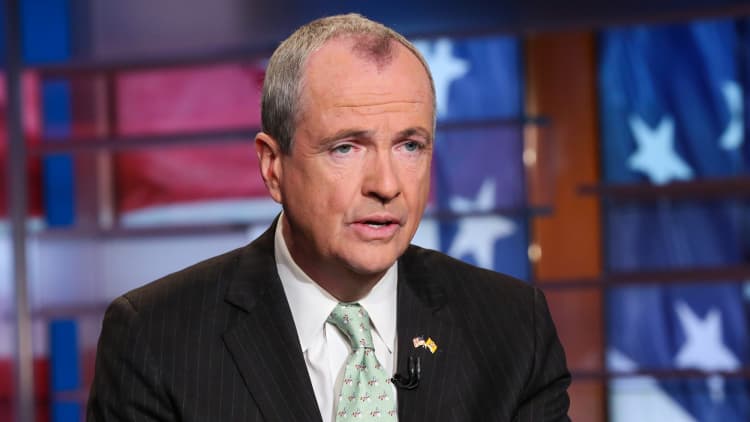

Getting it up and running took some doing, however, including coordination with city hall. "Christ Hospital's leaders were very proactive putting in place policies to protect the public," says Jersey City mayor Stephen Fulop. "They were the first hospital in Hudson County to set up a screening tent." Fulop stepped up, too, fast-tracking permits from the fire department to use outdoor electricity and propane heat, and extolling the tent during an onsite press conference when it opened.

What lies ahead

As the Covid crisis stretches into its third month, with death, fatigue and fear affecting Christ's workforce, another role for the hospital's leaders is balancing empathy and compassion with strength and resolve. "For me it's knowing when they are at their most distressed," Vieira said of the nurses. To see that firsthand, she dons scrubs and rounds with them, seeing their patients and the risks they're facing. She cries with them when another death is too much to take. "Just supporting them," Vieira said.

Duffy, who has an extensive nursing background, rounds with the nurses as well. "I'm proud to be out there touring with RNs in the hot zones," she said. "It makes me more relatable to them, knowing I understand their situation."

If they want to vent frustrations, she listens. "Sometimes their situation is so emotional, I tear up, and that's okay," Duffy said, admitting that stalwart leaders have emotions, too. "Showing them doesn't make you look weak."

Even so, circumstances can dictate when to emote. Woods confessed to a few sobbing episodes while driving home at night.

"When I'm in the emergency room, things are moving so fast, you don't have the opportunity to let your walls down," said Jones, who choked back tears as she spoke those words. She paused again when recalling having to leave her teenage son home alone after he contracted Covid. "Coming to work and putting on the brave facade so everyone felt safe and had strong leadership was probably the hardest thing," she said, adding that her son recovered and is fine. "But I had a job to do."

Now nurses and other frontline workers would like to see managers come up with other plans to help the staff cope with anxiety and the lingering trauma of watching so many patients die. "That could include a post-Covid huddle, onsite counseling and time off since the hotline is just not enough," says the Christ Hospital nurse who requested anonymity.

Jones and her fellow leaders at Christ Hospital will still have their jobs to do once the pandemic is over — hopefully, that is, because the hospital's future remains uncertain. Last fall CarePoint announced it would sell Christ and one of its sister hospitals, Hoboken University Medical Center, to RWJBarnabas Health, based in West Orange. Negotiations have been held up, though, over a property dispute involving a third party. Fearing complications could force Christ to close, Jersey City recently passed an ordinance specifying that the building is zoned only as a hospital.

Christ was already on shaky financial ground, and deep revenue losses from not being able to do non-urgent elective surgeries and a 60% decline in ED volume during the Covid crisis has made matters worse. Nearly $32 million in federal stimulus money is helping, Woods said, "but the fate of Christ is still lurking."

In the interim, Mayor Fulop said that Christ Hospital's rapid and robust response to the pandemic reaffirms its importance to the community. "The city is going to do anything we can," he stated, "to make sure it stays a hospital."

Disclosure: Christ Hospital's chief medical officer, Dr. Tucker Woods, is the author's nephew.

*This story has been updated to include comments from the nursing staff at Christ Hospital and leaders of the Health Professionals and Allied Employees of New Jersey.