Some companies are taking a harder line when it comes to return-to-work, telling employees that failure to comply could impact bonuses, work assignments or other performance measures.

In the knowledge worker world, Google, JP Morgan Chase, and law firms including Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom, and Davis Polk & Wardwell, are among the companies that have made clear to employees that a return-to-office mandate is — as the word intends — not an optional measure, and in some cases, there will be consequences for non-adherence to the policies.

This marks a shift from the incentive culture that many companies have been using to lure workers back to the office post-pandemic. Many of the carrots they've been dangling, including free food, happy hours and group-bonding activities, haven't necessarily been successful in prodding workers to fully compile with in-office mandates. And even when there's not a widespread flouting of the return-to-work policy, companies have been more inclined to make their expectations crystal clear, amid layoffs and hiring slowdowns.

Human resources experts have warned employers over the past few years that firm-wide mandates come with the risk of losing top talent along with employees that firms might be comfortable with letting go. But with the job-hopping that has taken place during the pandemic years slowing — and in particular signs that "The Great Resignation" is over — employers may see a chance to get the office back closer to what it once was.

"Organizations are viewing this as an opportunity to put in some more punitive measures that they probably wanted to do earlier, but were hesitant to do because they didn't want to risk losing employees," said Bradford S. Bell, The William J. Conaty Professor in Strategic Human Resources and Director of the Center for Advanced Human Resource Studies at Cornell University's ILR School.

If employers are feeling a little bolder about the balance of power between management and labor, here are ways management professionals say companies should approach these decisions.

The in-office tide may shift more easily for some workers

Companies may be buoyed by the growing recognition that not everyone wants to work from home or enjoys doing so. The desire to be in the office could be even more true for new entrants to the workforce. Notably, a March survey by recruiting firm LaSalle Network showed that of the more than 2,500 soon-to-be college graduates polled, only 4% wanted full-time remote work. By contrast, a whopping 87% said they'd prefer a hybrid schedule.

But workforce demographics vary widely when it comes to the benefits, and the desire, to return to the office. Sallie Krawcheck, the former Citi CFO and head of global wealth management at Bank of America, recently told CNBC that the CEOs who want to "get back to the way it was" are ignoring a big problem: the work environment that existed pre-pandemic "worked for white men, not everyone, and certainly not women and under-represented groups," she said.

Companies need to look closely at performance data

When making decisions to enforce an in-office policy, companies should consider whether there is a measurable benefit to doing so; they shouldn't just assume that because someone is at her desk, she is more productive than she would be at home, said Lynne C. Vincent, associate professor of management at the Whitman School of Management at Syracuse University.

Ideally, companies should track productivity over several months. "They should be data-driven decisions because otherwise you could be losing valuable talent if you are implementing policies that don't support productivity and don't support your culture," Vincent said.

Consider the cultural implications

Companies also need to consider why being in the office is so important such that punitive measures for non-compliance may be in order. Highly innovative companies, for example, might feel a compelling desire to have employees in the office three days a week for collaboration and connection purposes.

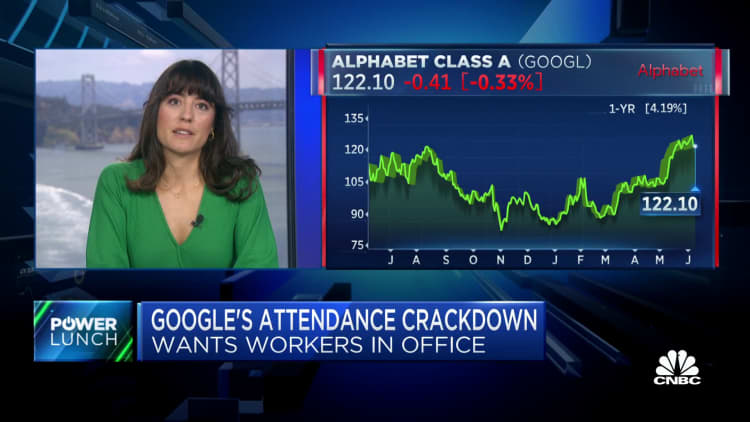

That's some of the impetus behind Google's decision to tell staffers that managers could take long-term non-compliance patterns into account when assessing their performance. Additionally, remote-only options will be limited going forward, according to the company's new policy. Employees who work from the office at least three times a week report feeling more connected to their colleagues, a company spokesman said.

Help employees understand specific 'whys'

Employees may not feel as compelled to be in the office if they don't understand what the company expects to gain by having them there, said Jenny von Podewils, co-founder and co-CEO of Leapsome, a platform that seeks to improve employee performance and satisfaction.

Managers should offer specific reasons why being in the office is critical to its operations. This could mean, for instance, spelling out to the sales team that Mondays and Wednesdays are in-office days because that's when the bulk of customer interactions happen, and making clear to engineering that Thursdays are in-office days because that's when code reviews happen.

"A lot of the policies I've seen are very general, so they don't get the specific buy-in because people don't see why it's relevant to them," Podewils said.

Leave room for exceptions

Companies need to offer some flexibility, unless they want to risk losing workers or experience more quiet quitting, management professionals said.

There may be legitimate reasons certain employees may not be able to meet their in-office expectations, said Rubab Jafry O'Connor, distinguished service professor of management at Carnegie Mellon University's Tepper School of Business.

Companies should seek to understand what issues may be preventing them from compliance and whether they are legitimate considerations. Is there a health issue, for example, or a child-care issue? Is the issue temporary and can the company do something to help?

Try to build in flexibility in other ways

To ease the rigidity of in-person mandates, companies may be able to offer flexibility in other ways. Options could include flextime, offering more vacation or personal days, creating a bank of days employees can use to work remotely and increasing the number of company-wide remote days.

Law firm Davis Polk, for example, is offering employees the option to work 16 days remotely each year. Between Sept. 5 and the remainder of this calendar year, employees are entitled to choose five days to be remote.

This comes as the company will start mandating employees be in the office four days a week, up from three days, after Labor Day. The company has also told its workers that not complying with its in-office mandate could negatively impact their performance and bonuses.

"The key driver behind our in-office attendance philosophy is a desire to provide all members of our community with best-in-class professional development opportunities, including mentorship, training and the opportunity to create more meaningful relationships with others at the Firm," managing partner, Neil Barr, wrote in the memo.

Be willing to lose employees

Companies that take hardline measures need to be willing to lose employees over this decision, management professionals say.

"The person and the organization have to fit together," Vincent said. "When that happens, it's productive and helpful. If it's not happening, maybe moving on is the right step."