This summer one of IKEA's two retail stores in the San Francisco area will start producing electricity from biogas after it installs a fuel-cell system manufactured by Bloom Energy. For IKEA, Bloom's fuel cells will help offset carbon dioxide emissions and contribute to the global home-furnishings chain's 2020 goal of being energy-independent. For Bloom Energy, IKEA's installation of its fuel-cell technology marks yet another point of growth for the cleantech company, whose list of big-name customers also includes eBay, Google, Adobe, Coca-Cola, Apple and more than 60 others.

Read More Meet the 2015 CNBC Disruptor 50 companies

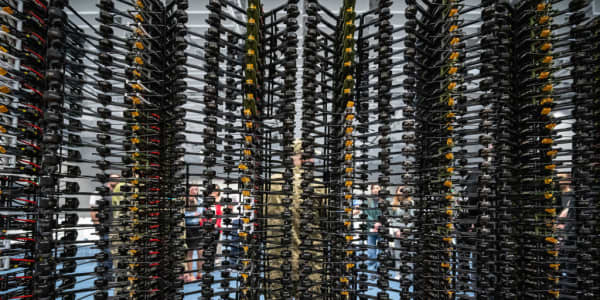

Launched in 2001, the fuel-cell company headquartered in Sunnyvale, California, makes solid-oxide fuel cells that convert natural gas or methane into electricity. Bloom Energy (ranked No.3 on CNBC's Disruptor 2015 list), then installs stacked units of these fuel cells—known as Bloom Boxes or energy servers—in customer locations, signing long-term contracts with customers to generate continuous electricity, at the point of consumption, with lower carbon dioxide emissions.

The privately held company, which skyrocketed to public prominence in 2010 after a CBS News "60 Minutes" profile, has raised a whopping $1.2 billion in funding since inception—including $130 million last December in a convertible note offering—from the likes of New Enterprise Associates and Kleiner Perkins Caulfield & Byers (Kleiner Perkins partner John Doerr is on Bloom's board; Al Gore remains a Kleiner Perkins partner today). Madrone Capital, associated with the Walton family of Wal-Mart, has also invested in the company. As of 2014, Bloom had installed more than 130 megawatts of its fuel cell units in the U.S.

But one question hangs over Bloom Energy: Why hasn't it gone public yet?

Read MoreGoogle is even more influential than you think

While the company declined to comment for this article, analysts and investors have their own theories. "People suspect that they're one of the companies in the queue to try to see if there's money in the public markets," said Troy Ault, director of research at the Cleantech Group.

In 2012, Bloom investor and board member Scott Sandell, who was unavailable for an interview, said Bloom would attempt an IPO in late 2013 or early 2014. Those dates have come and gone and have left observers of the cleantech industry wondering. "Anything less than an IPO or a big acquisition would be a disappointment to the firm's investors and shareholders," wrote Greentech Media's Eric Wesoff in December. So is 2015 the year Bloom Energy files for an IPO?

Michael Dempsey, a research executive at venture capital research firm CB Insights pointed to the $130 million via convertible note as a sign of an equity valuation that could be aggressive. A convertible note is often a signal that another equity round could only have been executed at a reduced valuation.

Kathleen Smith, principal at IPO tracker Renaissance Capital, said an IPO for Bloom makes some sense in the current market because alternative energy deals have fared reasonably well. But investors are valuation sensitive. The IPO market may not be ready to pay high premiums off the last rounds of private financing, and on the other side, Bloom's private investors may not be willing to accept a valuation markdown triggered by an IPO.

"This company was supposed to be public by now, and investors are going to need a big exit with the funding they've raised," Dempsey said.

Evolution of the industry

Bloom has a couple things working in its favor. The growth of the fuel-cell industry has been helped by the overall reduction in the cost of fuel-cell technology, said Scott Samuelsen, director of the National Fuel Cell Research Center at the University of California, Irvine. High-temperature fuel cells, like those produced by Bloom Energy, can now be manufactured from ceramics instead of expensive precious metals like platinum. And the price of producing energy from fuel cells has also decreased considerably from the $10,000 per kilowatt figure of the early 2000s.

"The fuel-cell companies that are public are beginning to demonstrate costs that are beginning to approach $3,000 per kilowatt," Samuelsen said. "The market is beginning to recognize fuel cells as being a viable option."

Read MoreBuffett vs. casinos? Inside Nevada's solar wars

But manufacturing, installing and maintaining fuel cells costs big money, and the big unknown when it comes to Bloom Energy is whether the company is profitable. Fortune reported in 2013 that the company expected to be profitable that year. Bloom Energy doesn't disclose its financials, and the company declined to comment for this article.

"They've focused for a time on installing as many units as they could in proving out the model," said Ault. "But does that mean they're knocking out of the park on the revenue graph? They've been quite secretive, and probably rightfully so, on all sorts of aspects of the company."

It's kind of like the stars are aligning in 2015.Scott Samuelsendirector, National Fuel Cell Research Center

The cost of the company's first-generation energy server, a 100-kilowatt model it no longer sells, has been approximated at between $700,000 and $800,000, meaning the cost of producing energy was between $7,000 and $8,000 per kilowatt. Samuelsen said Bloom is targeting a cost of $2,000 per kilowatt. Today the company offers multiple financing options to lower the costs of its fuel-cell systems, including a power-purchase agreement where Bloom installs its energy servers on a customer's premises and takes on all the costs of maintaining the system, charging the customer only for the electricity generated. In 2010, Bloom announced it hoped to one day sell home units of its Bloom Box for $3,000.

Bloom's fuel-cell systems are also eligible for a nationwide 30 percent federal tax break, as well as state subsidies. Since 2001, at least $230 million in rebates through California's Self Generation Incentive Program have gone to customers who've purchased Bloom energy servers.

Read MoreRenewable energy hasn't been this big since wood

"The fuel-cell deployment could not have been successful to this point without incentives," said Sameulsen, speaking generally about how fuel-cell companies have been selling their products.

Of course, cleantech isn't a sector where venture capitalists should expect quick, easy or even successful returns (Solyndra, anyone?). FuelCell Energy, one of a handful of public fuel-cell companies, finished its 2014 fiscal year by recording its second-highest quarter of sales and was still $5.5 million in the red in Q4, although analysts predict FuelCell Energy will be profitable by 2016.

Still, the future of the fuel-cell industry looks bright. According to a 2014 report from Navigant Research, the global revenue for stationary fuel cells will grow from $1.4 billion in 2013 to $40 billion in 2022. GE announced last summer it was looking to commercialize its own solid oxide fuel-cell technology, marking another big player in the sector. And while funding for cleantech continues to slide—down 72 percent year-over-year to $130 million this quarter, according to the latest MoneyTree cleantech report—a substantial amount continues to go toward smart grid and energy storage.

"It's kind of like the stars are aligning in 2015," said Samuelsen.

If Bloom were to go public in 2015, investors would be looking for two main things, said Matthew Nordan, managing partner at MNL Partners: "What is the path to cost down, and can you see a path to widespread adoption without subsidy? And those are both open questions."

For those keenly watching Bloom Energy, only time will tell.

"These sorts of distributed generation, especially as a service, businesses—it's not a clear-cut rocket ship to an IPO prospect," said Ault. "There's always a bit of a tug-of-war about what time is right."

—By Andrew Zaleski, special to CNBC.com