We keep hearing the foreboding statistics: 10,000 baby boomers in the United States turn 65 every day; our aging population is expected to double in the next 20 years and swell to 88 million by 2050; 75 percent of Americans over 65 live with multiple chronic health conditions, ranging from diabetes to dementia.

It is no secret, either, that the nation's already-strained health-care system is trying to keep sick and longer-living seniors out of hospitals, assisted-living facilities and nursing homes and instead in their own homes, which is where they want to live out their golden years. But that has shifted the caregiving burden onto family members, who are increasingly stressed and often supplemented by personal-care aides (also referred to as certified nurse assistants, personal-care assistants or home health aides) employed by thousands of home-care agencies across the country. Nurses and other skilled practitioners manage in-home medical needs, such as administering medications and wound care, while the personal-care aides cook, shop, clean, bathe, dress and generally offer companionship.

The U.S. spent an estimated $103 billion on home health care last year, a number predicted to reach at least $173 billion by 2026, according to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, which put total health expenditures in 2018 at about $3.67 trillion. CMS, veterans programs and private health insurance cover a portion of in-home care, although the estimated value of unpaid care provided by family caregivers added an astounding $470 billion to the mix, according to a 2016 report by AARP — not to mention the drain on family budgets and seniors' nest eggs.

Looking to alleviate these daunting financial burdens, lawmakers in several states, including California, Arizona, Wisconsin and Rhode Island, have proposed providing state income tax credits for families that need help with home caregiving.

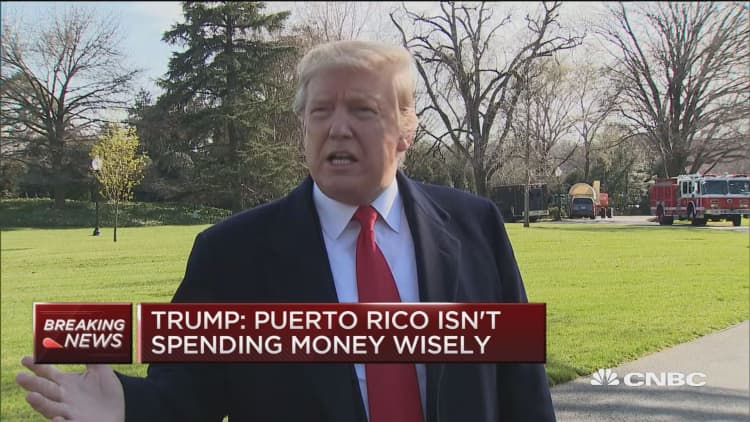

As all of these realities coalesce, we're starting to hear warnings about the fact that while the demand for all types of home health-care workers skyrockets, the supply cannot keep pace. This presents a looming national dilemma for the workforce and entities that hire, train and try to retain them, as well as the public and private sources that pay them. Consider, too, that while the Trump administration pursues its stringent anti-immigration agenda, one-quarter of these workers are immigrants — and the possibility that draining that labor pool could further intensify the shortage problem.

"We are on the edge of a crisis," said William Dombi, president of the National Association for Home Care & Hospice, a trade association in Washington that represents 33,000 home-care and hospice organizations. "We are not prepared for what's coming. Our concern is that the demand is going to outstrip the supply unless we see some dynamic changes occur."

A profession in need of reform

Dombi agrees with other home health-care experts who advocate for better compensation, benefits, training and advancement opportunities for personal-care aides. But he also insists that a huge part of the problem is that the profession simply doesn't get the respect it deserves. "These are workers taking $10-an-hour jobs, often without benefits, to provide services to extremely vulnerable people, doing work that 99.9 percent of the population would like to avoid doing," he said. "There has to be a change in our culture to respect these workers and hold their jobs in high esteem."

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics compiles data on this workforce, combining both home health aides (skilled nurses) and personal-care aides. As of 2016, they numbered 2,927,600. In 2018 their median pay was $11.12 per hour. Overall employment of in-home aides is projected to grow 41 percent from 2016 to 2026 — translating to 7.8 million job openings — a much faster clip than the average 7 percent for all occupations. Nearly 60 percent work full time; turnover rates are around 50 percent.

We are on the edge of a crisis. We are not prepared for what's coming. Our concern is that the demand is going to outstrip the supply unless we see some dynamic changes occur.William Dombipresident, National Association for Home Care & Hospice

Because a growing number of large employers — including Amazon, Target and McDonald's — and some states have raised minimum wages up to $15 per hour, or are attempting to, there is increased competition for low-paid workers, more so considering the tight labor market. Meanwhile, federal and state governments set fixed reimbursement rates for Medicare and Medicaid recipients, effectively capping workers' wages, and there's little political will to raise rates. Plus, part-time workers seldom receive overtime pay, health insurance or other benefits, making the profession even less attractive.

According to the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute, a New York-based organization that studies the home health industry nationwide, 46 percent of this workforce is ages 45 to 64, 87 percent are women, 60 percent are people of color, and 29 percent are immigrants, though how many are undocumented is unknown.

Every state legislates its own hiring and training rules and regulations for home health workers, but typically the job requires a high school diploma or equivalent and no related experience. If the employer is reimbursed by Medicare or Medicaid, federal law requires aides to receive 75 hours of training, including 16 hours of on-the-job instruction. States can then choose whether to mandate additional training. Private agencies that do not accept Medicare or Medicaid, as well as families and individuals who opt to hire aides at their own expense, are not subject to certification requirements.

The family caregiving burden

Beyond alarming statistics, the real-life aspect of this issue is that nearly everyone these days seems to have a hardship story to tell about caring for an elderly spouse, parent, sibling or friend, like the following one. Details were provided by family members, who requested anonymity.

By the time Elizabeth was diagnosed with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at age 83, the limited money her late husband left her was dwindling. Her three children agreed she'd remain in her condo, despite the high rent, and they'd tag-team as caregivers — a laudable task considering their mom was housebound, on oxygen 24/7 and increasingly frail and dependent. Plus, they all had full-time jobs.

As the months passed, caregiver stress kicked in, until the family decided they needed outside help. For 14 months Medicare covered Elizabeth's in-home hospice care, daily for three hours, but not the $26 per hour for the half-dozen personal-care aides from local agencies who intermittently relieved her children. While the aides were generally reliable, there were numerous last-minute cancellations, and a couple of aides had to be replaced after Elizabeth complained they were "mean."

Her funds nearly depleted, Elizabeth was preparing to move in with her daughter and husband across town, when she fell twice, leaving her bedridden and too weak to travel. That necessitated a 24/7 live-in aide, who cost $280 a day out of pocket for nearly six weeks. When Elizabeth died at 86, she was essentially broke.

Although her family was proud of the care they'd provided and forever grateful to the aides — a few attended her memorial service — Elizabeth's experience serves as a microcosm of what ails the home health-care system, particularly its workforce. Finding a cure is becoming critical as this supply-and-demand quandary escalates.

Expanding scope-of-practice laws

In his 2017 book "Who Will Care for Us: Long-Term Care and the Long-Term Workforce," MIT Sloan School of Management professor Paul Osterman confirms the dire numbers portending an upcoming worker shortage. And he agrees that wages and benefits must improve. Yet the most prudent pathway, he contends, is to change what are known as scope-of-practice laws and allow personal-care aides to receive additional training and permit them to take on certain medical duties — such as managing diabetes, Alzheimer's care and physical therapy — currently performed by nurses and other skilled practitioners per individual state laws.

This fundamental change would not only raise the stature of the profession, increase compensation and address shortage issues by attracting new hires, Osterman said, but "it would also save the health-care system money by keeping people out of hospitals and nursing homes."

"And the money to pay for upgrading skills would come from those overall savings," he added.

AARP, which represents nearly 38 million Americans over 50, vigorously promotes in-home health care yet also recognizes the shortfall in the workforce. "That's why family caregivers have to keep stepping in," said Susan Reinhard, senior vice president and director of the AARP Public Policy Institute. Acknowledging, too, that people are not clamoring to become a personal-care aide, the organization also advocates for expanding scope-of-practice laws. "We are working on that at the state level," she said.

Reinhard cautioned, however, about possible resistance from nursing unions "that feel only nurses should be able to do certain things." She countered, though, that upgrading in-home aides wouldn't necessarily disrupt the nursing profession as a whole. Rather, the newly skilled aides would simply be better able to offer a wider range of services for individuals in their homes.

Besides, while not on site, nurses and physicians would still supervise aides in acute-care situations. And, by the way, "that also helps family caregivers, who wouldn't have to run home to give a medication because the aide isn't allowed to," Reinhard said.

The big immigration quandary

Immigration issues erupting throughout the U.S. culture and economy have spread to the home health-care industry, where 1 in 4 aides hails from another country, according to Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute. As public anti-immigrant sentiments fester and proposed federal policies to severely restrict immigration gain traction — especially among low-skilled immigrants — workforce shortages in the industry could be further exacerbated.

Fastest-growing low-wage jobs in the US

| Low Wage | 2018 Jobs | 2023 Jobs | Jobs Added 2018 to 2023 | 2018 to 2023 % Change | Median Hourly Earnings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home Health Aides | 926,500 | 1,134,232 | 207,732 | 22.42% | $11.17 |

| Waiters and Waitresses | 2,666,275 | 2,812,556 | 146,281 | 5.49% | $10.01 |

| Retail Salespersons | 4,574,115 | 4,682,344 | 108,229 | 2.37% | $11.29 |

| Cooks, Restaurant | 1,349,883 | 1,450,547 | 100,664 | 7.46% | $12.06 |

| Nursing Assistants | 1,522,723 | 1,619,107 | 96,384 | 6.33% | $13.23 |

| Security Guards | 1,210,962 | 1,272,926 | 61,964 | 5.12% | $12.97 |

| Receptionists and Information Clerks | 1,104,928 | 1,174,389 | 69,461 | 6.29% | $13.70 |

Source: Emsi Occupation Data, 2018

"It is impossible to imagine that the sector would survive without immigrants," said Robert Espinoza, PHI's vice president of policy. Even without impediments, agencies might be dissuaded from hiring immigrants, regardless of their legal status, and patients may fear that their immigrant aide could be deported at any moment.

One solution would be to initiate a guest-worker visa program for in-home care aides, similar to the current H-2A program for the agriculture industry that allows foreign nationals to enter the U.S. legally to fill temporary or seasonal agricultural jobs. While not actually endorsing the idea, executives at two leading home health-care companies carefully worded their backing of immigration reform.

"We, along with our industry, would work to create an overall increase in immigration levels," said Jeff Huber, CEO of Omaha-based Home Instead Senior Care, which oversees 612 in-home care franchises in all 50 states and employs nearly 65,000 caregivers.

"We certainly would encourage good policies at the national level to make sure that in this marketplace we watch excess demand for workers, and if there is clearly wage inflation, we would advocate for sound solutions," said Bruce Greenstein, chief strategy and innovation officer at LHC Group in Lafayette, Louisianna, which operates 780 locations in 36 states with more than 25,800 clinical and nonmedical employees. Coincidentally, LHC does not operate in states that have the highest immigrant workforce.

Leveraging new technology is seen as another way to address the in-home care dilemma. The global smart home health-care market is predicted to reach $30 billion by 2023, up from $4.5 billion in 2017, according to Research & Markets. At this year's Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, there were 25 percent more health-related exhibitors than in 2018, according to the Consumer Technology Association, the organization that presents the show.

Smart speakers and various voice-activated devices from Google, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft, Samsung and other tech companies remind caregivers and patients about medication schedules and doctor appointments, activate TVs, appliances and therapeutic equipment and communicate with remote physicians and nurses. Smart watches and other wearables monitor vital signs in real time and transmit data to practitioners. Telemedicine allows two-way video visits between doctors and in-home patients. There are even robots that serve as companions and also dispense medications.

"Technology can improve the quality of home care," said Osterman. "It can help make aides more effective and improve communications." Yet tech won't replace aides anytime soon, he said, and "it's not going to resolve the current shortage issue."